I Forgot to Remember to Forget: Three Poetry Chapbook Reviews

For National Poetry Month this year, I read three poetry chapbooks that revolve around memory. Childhood memory, historical memory, the body’s learned memory, how place or sound or smell or language or popular culture evokes memory—the chapbooks here all touch on one or more or many of these themes.

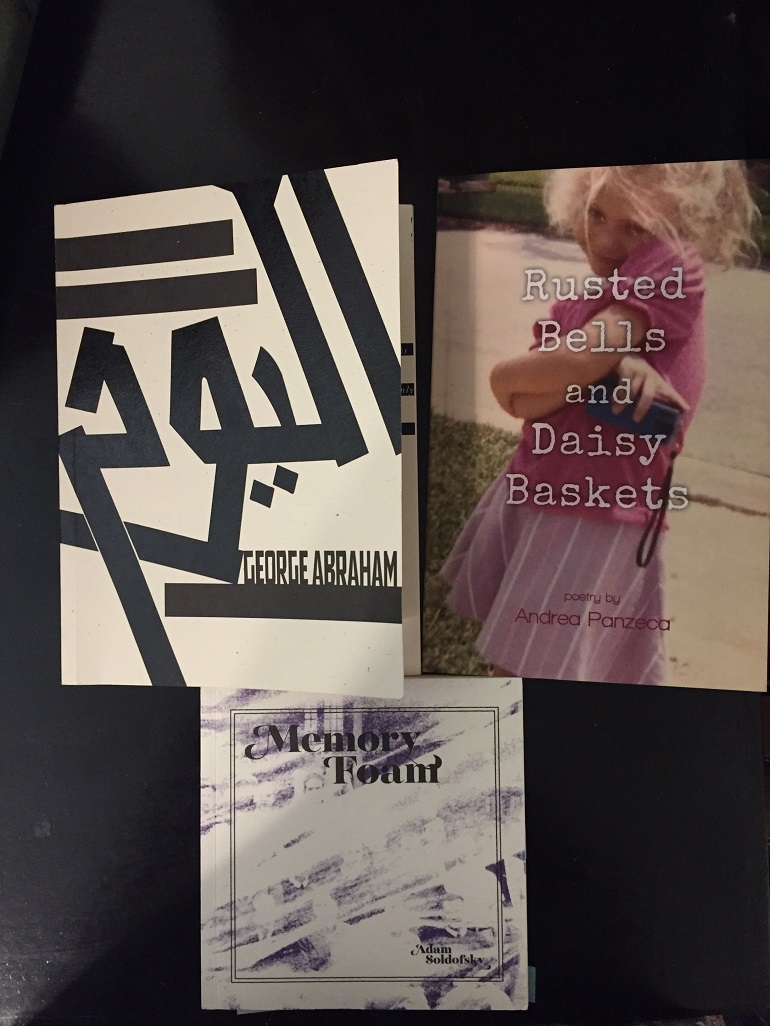

Al Youm by George Abraham (TAR Chapbook Series, 2017)

Sometimes, memory can be something inscribed onto the self as well as something acquired—identity through being subject to the world and protestations of being made object to it. George Abraham’s Al Youm, using a variety of forms of verse, examines what it means to be made and to make one’s self whole through that combination of the memories put upon its speaker and those the speaker knows to be his own: “what the textbooks fail to mention: / i was whole once,” (lines 1-2) Abraham writes in Part III of “Inheritance,” a poem that combines history of family and culture alongside dismantling palimpsest as history written for and about and over.

In “photographs not taken,” the images described are those the speaker wishes he had pictures of, for better or worse: those he wishes were true, failed to capture, and the abstracted ideas that might serve as reminders in the way a printed photograph often does. Abraham cunningly makes it difficult at times, though, to tell the difference: “my cousin shouting allahou akbar out of irony / after passing through TSA without / being quarantined for the first time” (lines 13-15) feels like a memory the speaker would want to hold onto, but it comes after “family portrait in post-racial society with / filter equating my olive skin to / my brother’s smoldering earth” (lines 10-12), a reality not yet exact or currently, it might seem, possible.

Abraham’s speaker uses verse to find ways to escape or rewrite or understand the oppression, the violence, he suffers because of his queer identity and (missing) country of origin. In “in which israeli parliament members compare palestinians to snakes so i become one,” Abraham writes, “joy can be a raucous / orchestra when the body empties / itself of all its music and you are reminded / of your unbecoming again” (5-8) and later concludes that “the only way to find home / in a countryless world is to build it in each other” (lines 31-32), resisting a lack of solid ground through fulfillment in the goodness of others, “who learned to dance / amidst the flames” (lines 36-37).

Abraham’s poetic forms range from erasure to ghazal to tanka to new ways of freeing verse from whatever Walt Whitman was freeing verse from when free verse came to be. The history mapped into this chapbook isn’t only a history of Palestinian queerness and diaspora and the body as “the site of a bloodied ecosystem” (Part III of “Inheritance,” lines 3-4), but also a history of world poetry’s past and future through exploration of these forms.

Memory Foam by Adam Soldofsky (Disorder Press, 2016)

With each turn of the page (of this chapbook/of time), what was once present fades to past and what was once whole and clear becomes slightly less so. The image Adam Soldofsky’s Memory Foam illustrates again and again tells this story and the story, too, of how someone’s eyes or necktie might, for a moment, capture attention before disappearing into the larger picture. The relationship between the image foaming over and the text is not difficult to determine once a reader becomes aware of the way the image is clouding over, its presence an unavoidable part of the reading experience of Soldofsky’s well-conceived and well-executed chap that reads as one long poem.

Soldofsky writes of both the speaker and humanity on the brink of disaster: “everything is in danger of / banishment or incorporation because I / am sad // and all doors belong to / death” (14). Awareness of one’s mortality that comes with aging is pitched against awareness of unnamed Anthropocene: “How soon can you start building a / tolerance for certain death // not often have I thought I’m here / on vacation” (30). One lives constantly knowing one will expire, and how to reconcile the eventual becoming of only a memory, only a “ghost in your head” (61) to someone else is what Soldofsky’s speaker uses these pages to parse.

Rusted Bells and Daisy Baskets by Andrea Panzeca (Finishing Line Press, 2016)

The interception of place by memory—how the past can tackle the present with stronger associations than the everyday is equipped with—is the major concern of Rusted Bells and Daisy Baskets by Andrea Panzeca, the title itself a phrase from the first poem that brings the speaker back to the bike-riding of her childhood.

The poems are often narrative journeys through their speaker’s memories, some which are recognizable, as in “One More Time for Pelican Drive”: “I excavated playground sand to try and get to China” (line 21) and others specific to the speaker, such as in “Frida and Fritz”: “When he gets up / to plod to their bedroom, he clutches his Glock / in one hand, the remote in the other—changes / the station from White Oleander to white noise” (lines 35-38). Many of the poems discuss the speaker’s father, who readers learn later died of a heart attack in her youth. This knowledge then makes the focus of the poems seem sharper in the way they explore the Florida and Louisiana coasts the speaker called home in her youth.

One of the best-worked poems is “On Turning 30,” which follows the journey of a library book. Here, again, there are moments a reader might relate to: “I wasn’t in danger now of joining / the 27-club with . . . Kurt Cobain. I was 10 / when he died and didn’t see him then as such a young / man” (lines 46-49) as well as those unique to the speaker and, in this case, her relationship with the book the poem is centered around, which she addresses as “you”: “I always told my parents I wouldn’t / move out till I was 35, but they left me in Florida at 18, / three years into your term” (lines 26-28). The book is never directly named, but we learn about its history while also learning about the speaker through her relationship with the book, whether it be for the author of the book, the book’s own publication and reading history, or for she who reads the book, carries it with her as she gets older, and then into what will be the rest of her life.