People of the Book: Leah Price

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Leah Price, professor of English at Harvard University and frequent writer on books, old and new media.

1. How do you define a “book”?

Earlier this year, the blogger Adrian Chen claimed that “a book is basically thousands of tweets printed out and stapled together between pieces of cardboard.” To my mind, a book is the opposite of thousands of tweets. It’s a medium with high barrier to entry—it used to be hard to produce one, and it remains hard to distribute one. Yes, most books quickly end up remaindered, and only a tiny fraction of them will ever be reprinted; they’re designed, in principle at least, for the long haul.

That said, “book” has meant different things to different cultures. It sometimes refers to a sequence of words that’s long enough to form a whole, though short enough that it’s not impossible for one person to read the whole thing—and even then, most books are treated more like a buffet in which readers graze for quotable quotes than like a meal whose different courses need to be eaten in sequence and it’s an insult to the chef if you don’t finish everything on your plate.

That said, “book” has meant different things to different cultures. It sometimes refers to a sequence of words that’s long enough to form a whole, though short enough that it’s not impossible for one person to read the whole thing—and even then, most books are treated more like a buffet in which readers graze for quotable quotes than like a meal whose different courses need to be eaten in sequence and it’s an insult to the chef if you don’t finish everything on your plate.

At other times and places, a book hasn’t referred to a sequence of words but rather to a material object—a roll of a manageable size, for example, or a codex that’s thick enough for its title to be spelled down its spine. This is one reason that UNESCO defined “book” in 1964 as “a non-periodical printed publication of at least 49 pages, …made available to the public”; but the redundancy of “publication made available to the public” points to what remains slippery in that definition. Where do you draw the line between publication and internal circulation, for example? And “of” begs questions as well. The early modern Sammelband is a book made of different works bound together by what we would today call the end user—it’s the reader, not the publisher, who assembled those parts into a whole that we’d recognize as a book. So “book” is a term that has fluctuated and been fought over long before e-books began to face off with p-books.

2 & 3. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading? And what has been your most unusual interaction with books?

My usual interaction: Like most people, I use books as a shield—a “do not disturb” sign when I don’t want to talk to my family; on the subway, as the equivalent of sunglasses. This isn’t a new way to use books: as soon as railroads were invented, Victorian etiquette experts also invented the axiom that “a book is the best resource for an ‘unprotected female’.”

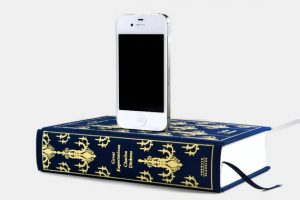

And my unusual interaction: I injured my back a few years ago, and since then I’ve found myself using books as furniture. I prop my computer monitor on books, because the normal height strains my neck; I also prop myself on books, because sitting on a low chair hurts my spine. And this had made me realize one of the things we sometimes take for granted about books: they’re one of the few cheap, ubiquitous household objects that are both uniform in shape (almost all books are some kind of rectangle) and varied in size (so that if you need to prop up one leg of a table, for example, there’s bound to be some book in your possession that fits down to the last millimeter). This makes them tremendously adaptable.

And my unusual interaction: I injured my back a few years ago, and since then I’ve found myself using books as furniture. I prop my computer monitor on books, because the normal height strains my neck; I also prop myself on books, because sitting on a low chair hurts my spine. And this had made me realize one of the things we sometimes take for granted about books: they’re one of the few cheap, ubiquitous household objects that are both uniform in shape (almost all books are some kind of rectangle) and varied in size (so that if you need to prop up one leg of a table, for example, there’s bound to be some book in your possession that fits down to the last millimeter). This makes them tremendously adaptable.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

For the Victorians whom I study, “furniture books” meant something different: what we would today call coffee-table books, books that are meant to be seen and not heard. But they also worried about what you could call the ethics of books use: is it fair game to hide behind the newspaper, use an encyclopedia as a doorstop, turn a newspaper into fish wrapping, match the binding of your bible to your dress, fill a study wall with hollowed-out books, decorate a living-room table with intact ones that you have no intention of opening? And is it legitimate to use books for ritual purposes, like kissing a bible before taking an oath in court? This was outlawed, for what it’s worth, in the early twentieth century – ostensibly because of germs, but also, I think, because of discomfort with treating a book as if it were a person. It disturbs us when the books that are supposed to spread Enlightenment rationality become enlisted in more superstitious kinds of attachment.

For the Victorians whom I study, “furniture books” meant something different: what we would today call coffee-table books, books that are meant to be seen and not heard. But they also worried about what you could call the ethics of books use: is it fair game to hide behind the newspaper, use an encyclopedia as a doorstop, turn a newspaper into fish wrapping, match the binding of your bible to your dress, fill a study wall with hollowed-out books, decorate a living-room table with intact ones that you have no intention of opening? And is it legitimate to use books for ritual purposes, like kissing a bible before taking an oath in court? This was outlawed, for what it’s worth, in the early twentieth century – ostensibly because of germs, but also, I think, because of discomfort with treating a book as if it were a person. It disturbs us when the books that are supposed to spread Enlightenment rationality become enlisted in more superstitious kinds of attachment.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

At the risk of sentimentality, I would keep the oldest books I own—oldest not in when they were produced, but in when they fell into my hands. My family moved every year when I was a teenager, so I now own only a couple of books from before college. Every August, books out on the curb; every September, a stranger’s cookbooks in a new sublet along with a stranger’s frying-pans. Cooking in their kitchen and reading their penciled checkmarks or metric-to-imperial conversions, I stepped in and out of their lives. So many of the books that made the deepest impressions on me are ones that I don’t own now because I never owned them.

But one of the few books that didn’t get left behind during that time was a two-volume selection of the Grimm’s fairy tales, translated by Lore Segal and illustrated by Maurice Sendak (New York: FSG, 1973). My copy is the second printing from 1974, which means that it probably didn’t enter into my possession when it was new—in 1974 I was three and my brother four, both too young to have a book like this bought for us. There’s no writing in it: it’s clearly a gift book (maybe for some subsequent birthday?), and I probably wanted to keep it clean. But in one of the shortest stories, “Mrs. Gertrude,” a corner of a page is torn off, I think because the story frightened me so much that I needed something to clutch.

My grandmother Gertrude was a pianist—her name is part of why the story about an old woman who turns girls into logs frightened me so much—and when she died last year we didn’t have a funeral. So the moment that took the place of casting the first dirt on her grave was dropping a piece of her sheet music down the recycling chute, down into what looked as far away as the underworld. No one will take old sheet music if it’s been scribbled up and taped back together the way well-used music always is.

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

The book was never the only game in town: it’s always coexisted with other media. A big part of any history of the book would have to be a history of its successive collaborations: authors interviewed on the radio; print manuals for digital devices; films adapted from books and vice versa. Rather than thinking about print and digital media as competing, it may help to borrow that old trade phrase: they’re “competing and complementary.”

The book was never the only game in town: it’s always coexisted with other media. A big part of any history of the book would have to be a history of its successive collaborations: authors interviewed on the radio; print manuals for digital devices; films adapted from books and vice versa. Rather than thinking about print and digital media as competing, it may help to borrow that old trade phrase: they’re “competing and complementary.”

But it’s true that we’ve suddenly become more aware of the shifting division of labor among different media. And that awareness has the unintended consequence of making intellectuals more invested than ever in taking the book as a proxy for certain larger cultural practices that we feel slipping away: attention, concentration, imagination, analysis. The problem is that for most of its history, the book hasn’t embodied any of those virtues. Most books throughout history have been utilitarian, instrumental, meant to be searched rather than read from cover to cover—think of the phone book. And even the absorbed, linear reading of a continuous fictional narrative from cover to cover didn’t use to be seen as a virtue: until radio and film and TV came along to compete, losing yourself in a book was a mark of idleness, not of industry.

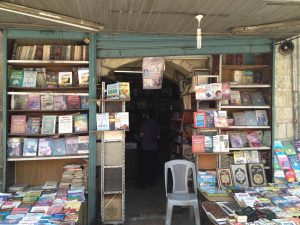

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

What a great question! My new year’s resolution was to put up a little free library in front of our house; I’m still working on it. Cambridge, MA, is a paradise for people who want to leave and find books on the street (at least, for those few months of the year when your discards don’t get buried in a snowdrift). But this neighborly generosity does have a PRISM-like surveillance potential: I confess to data mining one curb down the street where I’ve watched ‘90s dating guides give way to 2005-vintage wedding magazines, 2007-era pregnancy manuals, and board books published eighteen months later.

Librarians can protect borrowing records, but discarded books can tell you more about someone than the books that they keep. And yet I wish I could scramble my memory of these successive trash days to prevent prying into my neighbors’ lives. The judge who denied Kenneth Starr access to Kramerbooks’s record of Monica Lewinsky’s purchases was right to think that the books presented to President Clinton deserved greater privacy protection than did the matted poem she’d sent him on National Boss’s Day or the sterling cigar holder that the Starr Report lists among her gifts.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

The book has always been an early adopter. In the nineteenth century, booksellers pioneered advertising, self-service and consumer credit. In the twentieth, they were the first to try out bar-codes. Ted Striphas points out that Jeff Bezos might never have had the idea of selling books online if their distributors hadn’t already acted as guinea pigs for the digital inventory controls only later picked up by supermarkets. My corner bookstore, Lorem Ipsum, was founded by an MIT graduate interested in experimenting with pricing algorithms and inventory systems. So the only thing I think we can predict for sure is that the book will continue to behave unpredictably.

The book has always been an early adopter. In the nineteenth century, booksellers pioneered advertising, self-service and consumer credit. In the twentieth, they were the first to try out bar-codes. Ted Striphas points out that Jeff Bezos might never have had the idea of selling books online if their distributors hadn’t already acted as guinea pigs for the digital inventory controls only later picked up by supermarkets. My corner bookstore, Lorem Ipsum, was founded by an MIT graduate interested in experimenting with pricing algorithms and inventory systems. So the only thing I think we can predict for sure is that the book will continue to behave unpredictably.

______

Leah Price is Professor of English at Harvard University. Her books include How to Do Things With Books in Victorian Britain (Princeton UP, 2012) and The Anthology and the Rise of the Novel (Cambridge UP, 2000). She edited Unpacking my Library: Writers and Their Books (Yale UP, 2011); Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture (with Pamela Thurschwell); and (with Seth Lerer) a special issue of PMLA on “The History of the Book and the Idea of Literature.” She writes on old and new media for the New York Times Book Review, London Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, San Francisco Chronicle, and Boston Globe. She and Ann Blair have recently organized two conferences, “Why Books?” and “Take Note,” and together with Robert Darnton and Alex Csizsar they direct the faculty seminar on the History of the Book at the Harvard Humanities Center. Price is at work on a new book, Out of Print: Reading After Paper.