À La Recherche de l’Amérique Perdue: Fantasizing America

To say that the French have a love-hate relationship with the United States is an understatement. We’ll be tssk-tssking Americans for their alleged anti-intellectualism and Puritan mores, while unabashedly dreaming Technicolor dreams of New York and California and happily binging on series. There’s also a strong mainstream appetite for American literature, or at least one that delivers a certain brand of Americanness, all in stock images: New York, looming large in the French imagination of what America must be like, and all the noir imagery that goes with it (give us your grittiest cities and your most hardboiled fedora-wearing detectives); the small sleepy towns, their closets always full of skeletons; the Deep South, though that’s usually more popular among academics than in pop culture; the hallucinated landscapes sung by the Beat generation. Lately, Montana writers are also getting their share of the spotlight, with the allure of great open spaces.

But this means that you don’t have to be American to give us the America we want: more than a few French-language writers have dreamed of penning the next Great American NovelTM. Among these is a young Swiss writer, Joël Dicker. His novel The Truth about the Harry Quebert Affair has been marketed as no less than “a reflection on America, on the flaws of modern society, on literature, on justice, and on the media,” and crowned by several distinguished prizes, including one from the French Academy.

Never mind that, to get to the denouement, we must trudge through over 600 hundred pages of sloppy, cliché-riddled writing: young “brilliant” male writer in NY (where else?) is hit with writer’s block after the overwhelming success of his first book, and seeks out “genius” male mentor from college who lives as a quasi-recluse in New England and abuses the boxing/writing metaphor; mentor is falsely accused of murdering a teenage girl eons ago (but he did have a liaison with her, and he did love her like he loved no one else before); young writer takes it upon himself to clear his name. There’s also mentally ill women, jealous women, and a healthy dose of suburban suspicion. All in all, a brittle collage of genres, thriller noir and romance, sub-Rothesque cinematic realism and pseudo-experimental writing.

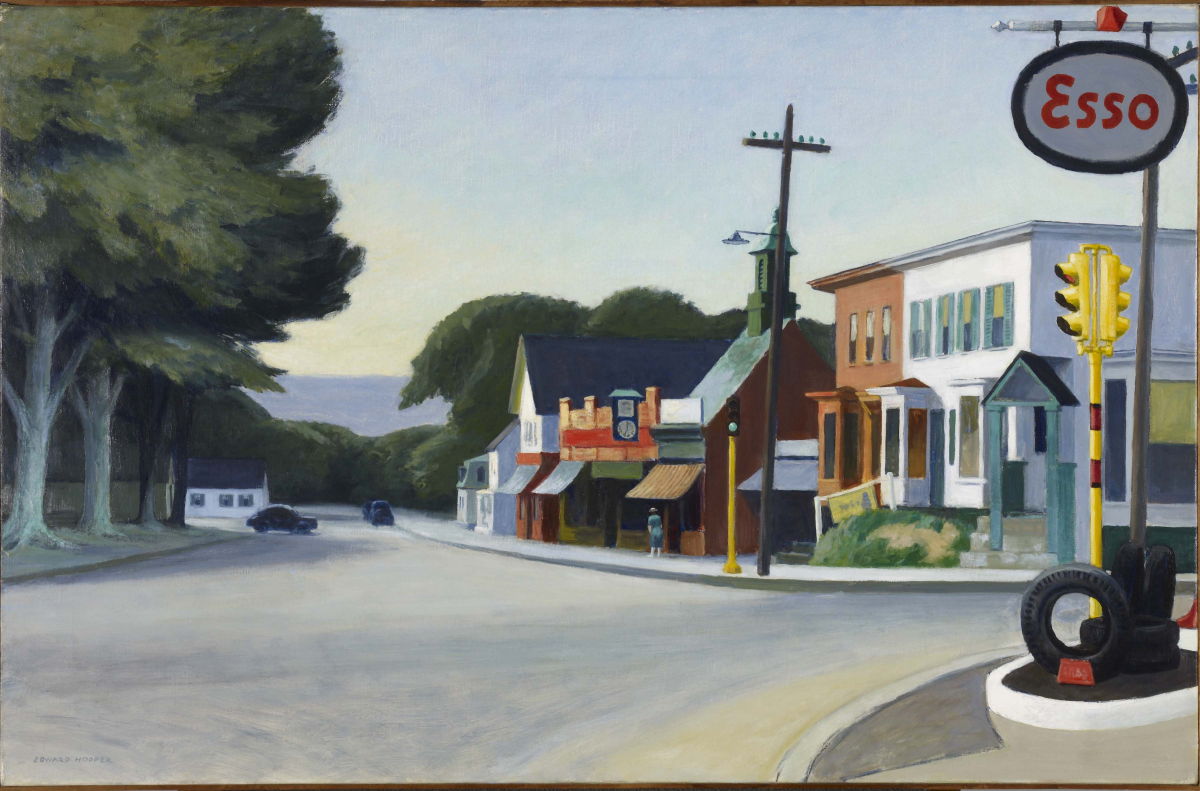

The interest of the book—at least for me—lies then in the way it attempts to sell us a version of America that we’re already familiar with, starting with the front cover, which, in the French edition (and the UK one for that matter), features a lesser-known painting by Edward Hopper—Portrait of Orleans. This was a deliberate choice by the author who saw in Hopper someone who captured with exceptional talent the “atmospheres of America”—and he’s not the only one. To the European mind, Edward Hopper is the quintessential American painter. Nighthawks especially condenses the entire myth of the nocturnal, lonely city life in the 40s, with its veneer of glamour and hint of lurking menace. Hopper’s works, especially the ones depicting urban settings, routinely pop up on the covers of books by American and European writers that are set in the US.

Portrait of Orleans, however, has less of the iconic feel to it, even though it bears Hopper’s distinct touch. It was painted in late August 1950, and pictures the Cape Cod town seen from the corner of Route 6 and Main St, according to notes written by Jo, Hopper’s wife (and a painter herself). On the right hand side, there’s an ESSO sign, then moving to the left, a row of low houses and stores, one with a bell tower, a tiny figure in a blue dress walking down the street away from us, the road receding in the distance, into a mass of trees. It’s at once full of signifiers and tremendously empty. Interestingly enough, Jo’s notes indicate that the most important point in the painting for Hopper—the dusky yet luminous sky—is artificial: Edward had “given up finding an evening sky in Orleans, so faked one of his own.”

Looking for anything in the book that would properly relate to the painting, that would justify its use as frontispiece, leads to nothing substantial. The book and the painting are both anchored in small-town New England. That’s about it. Props must be given though for choosing a lesser-known painting. But still, why then the enduring fascination with a certain vision of Hopper? Why the constant attempts to shoehorn him into any narrative that remotely deals with “urban/suburban America” and “loneliness”?

Portrait of Orleans was actually used to illustrate another article, published in the UK, about the author Marilynne Robinson. The caption read, “Portrait of Orleans by Edward Hopper: The protagonist of Lila ‘is uncomfortable with the stable world her husband wishes to provide her.’” It seems the painting is meant to illustrate the analysis of the characters; yet we’re still unsure of how the painting figures into the equation—is it meant to represent the safe and stable suburban world promised by her husband, or to allegorize the landscape of her mind, empty and vacillating?

It’s a pity that a painting such as Portrait, which has not yet been hackneyed by hermeneutics, should come to merely serve an illustrative purpose, reduced as it is to a handful of familiar symbols. Hopper’s paintings represent unsettling, liminal scenes, neither here nor there, and that’s what makes them riveting. His is no easy realism (many have pointed out he wasn’t a particularly good painter to start with, but this is precisely the point: to ask him for pure realism would be misguided). The scenes he depicted most often resided in his imagination (Nighthawks, for example, never existed). And I keep thinking about how Hopper used to work as a magazine & commercial illustrator, mostly to pay the bills, and resented it. Reducing his paintings to snapshots of a bygone, quasi-mythical but largely fabricated America on covers of books that vaguely embody an “Hopperian spirit” may be precisely the kind of reductive interpretation that strip him of any true imaginative power.