A Stone, a Leaf, a Southern Genius

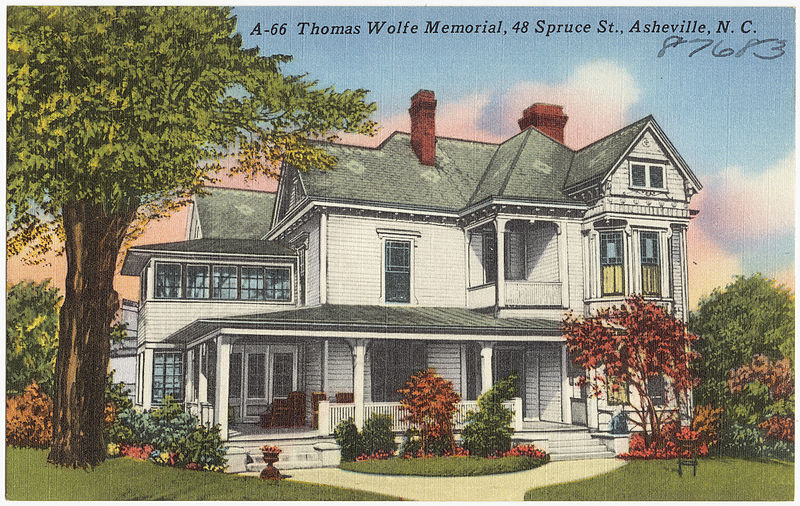

From the moment he steps onscreen in director Michael Grandage’s Genius Thomas Wolfe (played by Jude Law) is an aberration. At 6’5, the writer was literally larger than life. He often worked hovering over a refrigerator-cum-writing desk. He penned thousands of pages in an attempt to share his grand, all-inclusive vision of the United States. He journeyed to its opposite side (the Pacific Northwest), a trip that might have spurred his untimely death at age 37. He was one of the only Southerners on editor Max Perkins’ list of writers at Scribner’s. (Perkins turned down Faulkner at the behest of fellow alpha male Ernest Hemingway.) He obviously had talent. The recent film begs a question: Why is Wolfe so rarely mentioned in the 20th century American literary canon? One major reason—he was Southern.

Southern writers, when included in the national literary narrative, are often pinpointed for their eccentricities, like Flannery O’Connor and her famous pet peacocks or Truman Capote chaise lounging with cocktail in hand. Thomas Wolfe was eccentric too. The shoe fits.

Now, please don’t write me off as just another bitter Southerner trying to get a few words in edgewise about how my people have been maligned by the rest of my country’s people. I can admit some areas ripe for improvement. For instance, Southern writers tend to stick to regional subject matter, many of them choosing to continue to live and work in the South, avoiding the draw of a writerly NYC life. This can throw Southern authors under an isolationist glow and leave writing like Wolfe’s unexplored on dark shelves.

As teens, most of us are required to read The Great Gatsby and The Old Man and the Sea in school. Growing up in the South, I’d heard of Thomas Wolfe but never read him. I overlooked his books mostly due to their length. Years later, I gave one a try.

For those unfamiliar with his style, some of the first lines of the film Genius are pulled from the beginning of Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel:

…a stone, a leaf, an unfound door; of a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces…

Which of us has known his brother? Which of us has looked into his father’s heart? Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not forever a stranger and alone?

…Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When?

O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again.

—Thomas Wolfe, Look Homeward Angel (1929)

The language could be called heavy-handed, pretentious, and regional, but there’s no denying the power in it, the poetry.

Wolfe’s books sold well upon first publication. One of the dramas of the film is whether or not the titular genius is Wolfe or his editor Max Perkins, who helped shape the writer’s unwieldy, winding piles of paper into a seamless narrative. Wolfe strived to put everything into his books, every sensory experience he could recall, every word he ever heard. These words are often racial slurs—another reason why his books are often ignored in today’s classrooms. Wolfe wanted all of it in there—the good, the bad, the pretty, the ugly—he sought to capture life in America as he saw, heard, and felt it.

Had Wolfe lived longer, there’s a chance he might have repeated himself or run out of material, as the bulk of his writing is autobiographical. Perhaps he might have pursued new experiences abroad like Hemingway or resorted to alcohol like Fitzgerald. The writer’s young life is a testament to the search we all undertake to find our voice, our subject matter. All of us, Southern or not, are keeping our eyes peeled for that stone, that leaf, that unfound door—all things we hope to turn over to discover the truth of who we are, why we’re here, and where we’re going.

It’s an ambitious undertaking, one that may yet end in failure but one worth the effort of writing page after page, even if you need help sorting them out later. Perkins, perhaps more friend than editor to Wolfe, put it best: “…the trail he [Wolfe] has blazed is now open forever.”