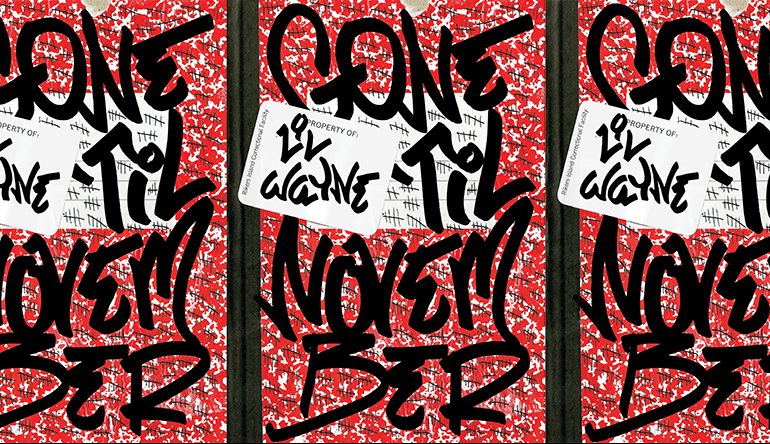

Boredom in Lil Wayne’s Gone ‘Til November

My son’s dad calls from jail almost every day. He’s been there for a few months now. He’s also been in involuntary protective custody for the majority of that time after getting jumped in his sleep, so he spends twenty-three hours a day in his cell. At some point during his free hour, we catch up on what the baby’s been doing and whatever else is new, and I eventually ask him what he’s going to do with the rest of the day. There are really only a few things he could be doing, like reading, working out, or making a hookup, so I ask things like What books are you reading? How many push-ups can you do now? What foods are you going to cook with?

My son’s dad calls from jail almost every day. He’s been there for a few months now. He’s also been in involuntary protective custody for the majority of that time after getting jumped in his sleep, so he spends twenty-three hours a day in his cell. At some point during his free hour, we catch up on what the baby’s been doing and whatever else is new, and I eventually ask him what he’s going to do with the rest of the day. There are really only a few things he could be doing, like reading, working out, or making a hookup, so I ask things like What books are you reading? How many push-ups can you do now? What foods are you going to cook with?

I thought a lot about our conversations while I was rereading Lil Wayne’s book, Gone ‘Til November, recently. The book is Lil Wayne’s prison journal from the eight months he was incarcerated on gun charges in New York City. I remember there being very little literary buzz surrounding the book when it came out in 2016; one of the only critical reviews was published by the LA Times, in which writer Baz Dreisinger calls the book a “flagrant missed opportunity.” She wanted more social awareness and creativity from the rapper. To her, Lil Wayne’s reading of Rikers Island is only “mildly unpleasant.” She admits that “prison’s psychological violence … is occasionally captured by Wayne’s spare, mundane, repetitive language,” but, for me, that was what made the book so engaging. It’s true that the book is not an academically researched text, but there is value in the way Lil Wayne presents his boredom.

Gone reads like a series of interconnected poems. It’s not Assata Shakur’s Assata: An Autobiography or Mumia Abu-Jamal’s Live from Death Row or Clifton Collins Jr. and Gustavo “Goose” Alvarez’s Prison Ramen, but it doesn’t have to be. Lil Wayne’s book, instead, offers access to the stream of consciousness produced by an imprisoned mind—Lil Wayne told Revolt that the book was just a journal he kept that someone else had suggested he publish and that he never even read back over the manuscript before it went to print, not wanting to relive the experience.

The monotony depicted in Gone is a tool used by the American prison industrial complex to dehumanize imprisoned people. Limiting what, when, and how inmates do things helps train incarcerated people to comply with inhumane living conditions. By tackling the monotony of prison life through routines and rhetoric, Gone ‘Til November helps redefine what’s considered productive in prison.

The community of people Lil Wayne falls into have been using food to keep busy long before he arrives at Rikers Island. They cook for each other, share snacks between one another, and eat together for celebrations. It’s so much food that Lil Wayne constantly worries he’s going to get fat. He’s always on the receiving end of extra sugar packets. God knows how many Dorito burritos this man has consumed. He’s very meta about the redundant food choices, though—probably because acquiring food is just something to do. He writes that “this is the kind of shit that has become worth writing about: eating Oreos and drinking grape Kool-Aid. Damn!” The overindulgence in food quickly becomes a coping mechanism for the drudgery of prison life.

That use of “Damn!” is one instance of many. He writes “Yeah!” or “Damn!” on at least every other page, like a generously used ad-lib. The repetitive language reads like a kind of call and response, like a reaction to whatever he has just finished writing, as if the tone of the line weren’t transparent enough alone. Even though his own mind was the only audience for his journal at the time of its writing, he hypes himself up in a way that reflects his occupation as a performer. All of the exclamation points he uses seem to serve a similar purpose—to manually insert emotion into a dire situation.

Lil Wayne’s tone is especially solemn when he catches himself slipping into assimilation. He says that “it’s crazy how jail can make doing what you wouldn’t regularly do make sense. I’ll have to be mindful not to get lost in this opposite world.” About a hundred pages later, he writes: “and because I was in jail, I was like, Damn, that [n*gga] is crazy … Oh well, what we eating tonight? Jail desensitizes a lot of things. The reality in here is so harsh. I will never understand how anyone think that this shit is cool.” It’s clear that his original fear has come true—he has been desensitized to the life prescribed for him in prison. His use of the word “crazy” in both statements is anticlimactic, and food continues to be an outlet for his emotional numbness.

Lil Wayne’s description of the culture continues to be pretty blasé, with his attitude reflecting the disempowered population he is a part of, even when matters are serious. At one point, he says: “I wrote some letters … Charlie cooked dinner … Al was mad that his meds didn’t come … and I’m bored out of my fucking mind … Jail!” This list of events addresses casual and serious situations, but they are all regarded with the same flatness. This happens again during his reflection on a fight: he writes that “there was a brief fight on the other side … don’t know who won/lost … and really don’t care … it’s just the type of stuff that’s talked about in jail.” He can’t seem to get interested in other people’s trauma, and that’s not abnormal. He’s taking things as they come. The repeated use of ellipses in these sections also suggests that there is an impulse to just keep the pen moving even while he’s thinking of what to write next, just to keep busy.

But beyond everyday things like making calls, eating, reading, working out, praying, and writing in his journal, Lil Wayne manages to keep up with his artistic career. Performing for inmates or being recorded rapping over the phone is what truly excites him. Knowing that he’s going to get out and still have the privilege of being himself motivates him through the end of his sentence. The arc of his journal entries turns positive (he describes himself as “happy” even) also because he is content with his ability to still be creative in a place that wears him down psychologically.

There are more exciting books written in and about imprisoned life, but the casual nature of Lil Wayne’s journal shows the complex side of playing it cool. He’s locked up with the best situation possible—money on his books, people coming to visit, fans writing him letters, protected from any kind of violence because he has the resources to sue—and yet, he still feels lost. Reading prison writing like this helps unearth systematically hidden stories and feelings.