Bridging the “Dreadful Gulf”: An Interview with Sarah Death

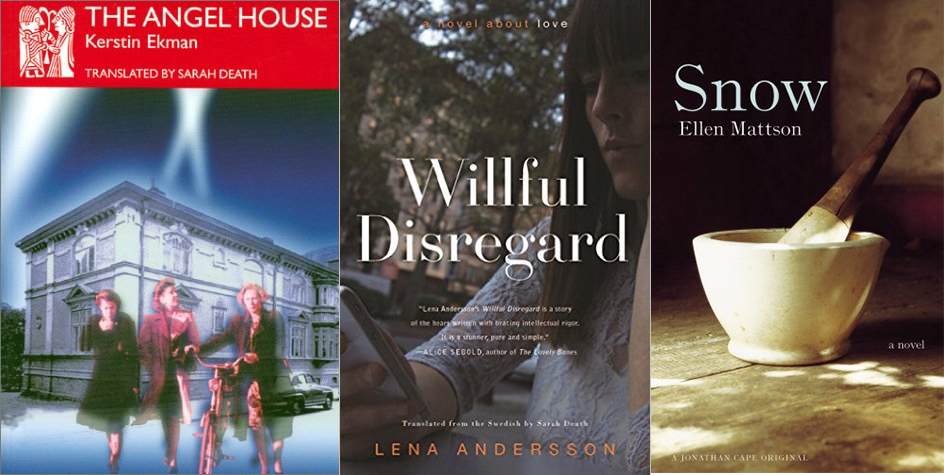

Sarah Death is a translator and scholar of Swedish literature. She edited the Swedish Book Review from 2003-2015 and lives in Kent, England. She has twice won the Bernard Shaw Translation Prize: in 2003 for The Angel House by Kerstin Ekman and in 2006 for Snow by Ellen Mattson. Her most recent novel translation is Willful Disregard, by Lena Andersson, which was published in the US by Other Press at the beginning of February. While Andersson is known primarily as a cultural and political critic, Willful Disregard is “a novel about love,” and tells the story of Ester, a young female academic who falls obsessively in love with an older, pretentious artist. It won the 2013 August Prize, the highest literary award in Sweden.

Sarah Death is a translator and scholar of Swedish literature. She edited the Swedish Book Review from 2003-2015 and lives in Kent, England. She has twice won the Bernard Shaw Translation Prize: in 2003 for The Angel House by Kerstin Ekman and in 2006 for Snow by Ellen Mattson. Her most recent novel translation is Willful Disregard, by Lena Andersson, which was published in the US by Other Press at the beginning of February. While Andersson is known primarily as a cultural and political critic, Willful Disregard is “a novel about love,” and tells the story of Ester, a young female academic who falls obsessively in love with an older, pretentious artist. It won the 2013 August Prize, the highest literary award in Sweden.

Graham Oliver: I love that this book starts with a brief treatise on language always being an approximation of reality, on there being a “dreadful gulf between thought and words.” Later in the book, we’re led as readers to question the usefulness of this belief, but how do you think this idea plays into the act of translation?

Sarah Death: Expectations certainly should not be lower; any self-respecting translator will be striving to bridge the gulf, if it exists. My focus was on the “dreadful gulf” between the way Ester presents things to herself and what the reader can increasingly see to be the blunt truth of the matter, namely that Hugo, the object of her affections, is incorrigibly self-centred and cares nothing for her except when he can use her to advantage. I was constantly aware of the need to encompass both aspects whilst still creating a readable flow.

GO: Andersson’s other works sound much more overtly political than this one. Was that a surprise to you when you read it? I also think the fact that she is known for being “one of the country’s sharpest contemporary analysts” is fascinating given this book seems to be a criticism of being overly critical. Should we read this as the author being slightly self-deprecating?

SD: You are right that much of Andersson’s previous work – and indeed much that has come since – is quite overtly political. Willful Disregard, her ‘novel about love’ (to borrow the sub-title) was thus a rather unexpected departure, though I am sure she would argue that the personal, too, is political. Andersson is a very funny writer and there is undoubtedly a hint of self-deprecation, although Lena and Ester are not the same person. The author reserves her sharpest scalpel for dissecting the power play between the sexes and examining the all-devouring, totalitarian nature of the emotion we call love – or ‘the malarial love itch’, as she puts it in the novel.

GO: I want to ask about one specific sentence that I really enjoyed. The narrator, who frequently zooms out to make broad observations like this one, says: “Interestingly, in general linguistic perception a ‘good friend’ counts as more distant than a basic ‘friend’ just as an ‘older person’ is younger than an old one.” That’s such a clever insight, but I was curious as to whether this came from Swedish seamlessly, or did you have to finesse the reference to have the same meaning?

SD: Yes, I loved this observation, too, so perceptive. It did indeed come fairly seamlessly from Swedish although I am generally happier rendering the individual word ‘äldre’ as ‘elderly’, rather than ‘older’, but then the sentence would not have worked so well in English.

GO: Some of the language in Willful Disregard seems to be purposefully stilted to show the protagonist being unable to turn off her overly critical, academic mode of thinking. I’m thinking here of lines like, “She did not like the censure she had allowed herself, the self-pitying passive-aggressiveness, the tone of rejection which, she knew, kills all desire and delight the other person might feel by the sense of guilt it engenders in them,” which comes after their first night together, as well as Ester’s dialogue when she’s trying to rationalize/justify her feelings and behavior to Hugo. Is it obvious when the language hits those notes in Swedish as well? Did you have conversations with the author about what the vocabulary accomplished?

SD: The original also has a series of long words, although the Swedish language’s large number of compound words can produce a slightly neater result. Ester is a woman who thinks that if she can clothe something in precise and impressive language, she can somehow fix it, so in my translation I felt I should try to do justice to that and not reduce or fudge her words, even though this can occasionally result in some rather densely written passages.

Unusually, I had no dialogue with the author in this project. Authors vary greatly in the amount of input they want – and the level of English-language proficiency they claim to have; Lena Andersson was happy to leave me to get on with the work in my own sphere of expertise – and I did benefit from an excellent UK editor and subsequently an attentive US one.

GO: I always end with a request for recommendations. What should we be reading from Swedish literature?

SD: Carl Jonas Love Almqvist’s Det går an (1839, literal title translation: It Can Be Done. Published in English as Sara Videbeck, 1919, transl. Adolph Burnett Benson) is a brilliant short novel that has aged extremely well. The novel was, for its time, a bold attack on marriage as an institution and women’s financial dependence. A new translation is surely overdue.

Elin Wägner’s Pennskaftet (1911, which I translated as Penwoman, Norvik Press, 2009) is the novel of the Swedish women’s suffrage campaign, a vibrant period canvas, spotlighting an era when women’s transgressions of the boundaries were still severely judged.

All the novels of Kerstin Ekman, including those as yet untranslated.

Lena Andersson’s Utan personligt ansvar (working English title: Limited Liability) is her follow-up novel, in which Ester finds herself in thrall to another love object with commitment problems. Andersson did not want Willful Disregard to be seen as an isolated case study, she said in an interview; her aim was to underline the pattern in human relationships.

You can read an excerpt from Willful Disregard at LitHub, click here.