Bruno Schulz and a Mother’s Tough Love

Like many things in my life, the writer Bruno Schulz is an example of how I used to focus on men. Men’s troubles, men’s heartache, men’s surprising capacity for emotion. The sight of a man crying would put me in a state. Not only did Schulz himself, with his curious, sorrowful semi-autobiographical fiction and artwork and tragic life story, elicit this kind of attention, but so did his character of the father. Recurring and central to Schulz’s interconnected stories (of which there are two collections: The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass), the child narrator’s father is a shopkeeper who gradually loses touch with reality. He breeds and raises rare birds in his attic and, maddened, fights off a swarm of cockroaches with a javelin until finally becoming a cockroach himself in the first in a series of metamorphoses, a myriad deaths (“each one shorter, each one more pitiful”) his family must endure.

But ever since I became a mother, something has shifted in my perspective, and I am growing ever more aware of the muted force managing and laboring behind the scenes of these extraordinary men. The secret agents quietly packing tomorrow’s lunches, noting the shortage of whole milk, calculating the day’s plans in correlation with naptimes and a change of clothes. They are mothers. Sweet, loving mothers who have taken it upon themselves to be the fixers and facilitators of family life.

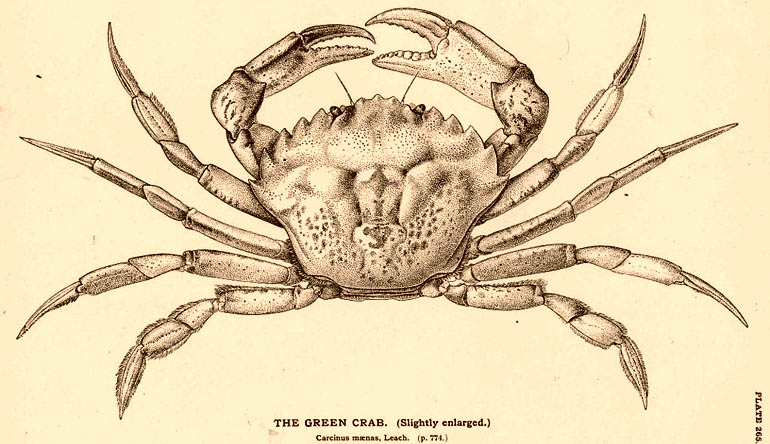

In “Father’s Last Escape,” the eponymous father undergoes his final transformation—into a kind of crab. The crustacean scurries through the family home, scaring its residents and getting caught in all sorts of precarious predicaments. Merciful and kind yet guiltily disgusted by this new creature, the family members lose their footing and grow untethered from their normal lives. Finally, when the situation becomes too upsetting to bear, Bruno’s mother gives the order to have the crab-father cooked and served for dinner.

Appalled, the narrator confronts his mother. “How could you have done it? If it were Genya”—the maid—“who had done it—but you yourself?”

Too distraught for words, the mother offers no response and is easily overlooked in this story, her motives written off as a moment of inattention or immorality. Her role in the story becomes even more forgettable when, after finding the sight of her cooked husband too upsetting to handle and ordering the dish to be exiled to the living room, the dead crab flees his destiny, never to be seen again, leaving behind one water-gray leg and some tracks in the tomato sauce.

I see it differently now. Bruno’s mother knew that to be the mom often means to take on the role of the bad guy. The one who informs everyone that, no, we can’t go straight to the party, we have to stop at home for a quick nap. Wait, you can’t jump into the water just yet, you have to put on sunscreen. Yes, bedtime is enforceable. No, baby can’t eat an entire ice cream cone.

Bruno’s mother, in this new reading, takes on the role of both sacrificer and sacrificed. She does what the entire household knows deep down must be done, placing herself in the role of the villain because somebody has too. Simultaneously, another outcome of her actions is that the rest of the family also feels complicit and morally reprehensible. But is it because her deed implicates them with her act, or with their own inaction?

There was nothing in the parenting manuals to suggest that motherhood would make me so rough around the edges. I knew I would have to be a disciplinarian in addition to a nurturer, but I thought this would be exclusive to moments when my child acted out or tried to put his finger in the electric socket. I didn’t think I’d be attempting to discipline everyone around me. I find myself saying “no” a hundred times a day, not only to my child, but to my husband, my parents, my in-laws, my colleagues, and my friends. I say no when a relative wants to show their love for the baby by overfeeding him. I say no when a friend invites us to a party that starts at seven. I say no when a client offers an urgent job on a day when my son stays home from school. I say no to myself a million times a day, when I feel like not cooking and instead feeding my son bread with nothing on it; when I want to lie around and stare at the ceiling rather than do my work when he naps; or when I feel like setting both of us in front of an episode of Gilmore Girls because I’m tired and out of ideas and the day doesn’t seem to end.

But saying “no” is just the tip of the iceberg. As my son approaches the terrible twos, I begin to practice the art of tough love. Suddenly I am ignoring his pleas for just another little snack come naptime, keeping a straight face when he cries because something he wasn’t supposed to be touching in the first place has fallen to the floor, and holding tightly onto his little hand as I say in the sternest voice I can muster, “No hitting.”

Bruno’s mother was living in a house controlled by the whims of a varmint and a man whose ego had grown so madly out of control that he would not allow his family to grieve for him and move on. When she saw that her loved ones were losing sleep at night for fear of an unwelcome visit, that the integrity of her household was compromised, and that the only outcome in sight would be to have odd and unpleasant Uncle Charles stomp on the crab, she decided an intentional act of tough love, performed by an affectionate hand, would be the lesser of two evils. She knew that to care for her family sometimes meant to do what no one else had the guts to, offering herself as the object of their shock and abhorrence so that they can rest easily at night, knowing they’d been cared for.