Bullets into Bells: Gun Violence and the Nuance of Suffering

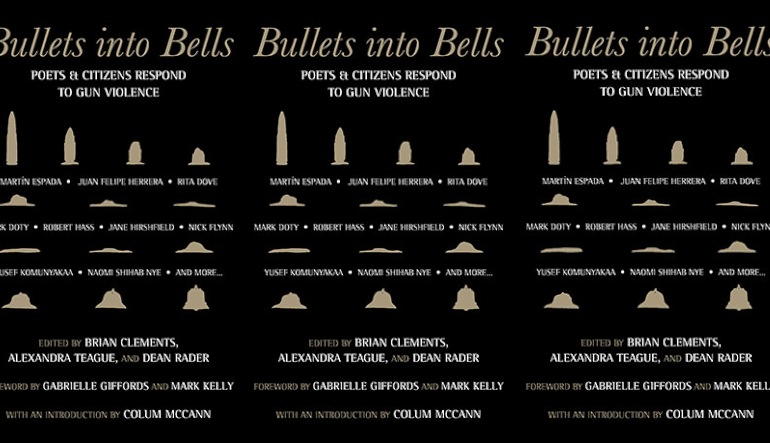

Just days before the fifth anniversary of the shooting at Newtown’s Sandy Hook Elementary school, Beacon Press published Bullets into Bells, an anthology of poetry and prose responding to gun violence in America. Edited by poets Dean Rader and Alexandra Teague as well as Brian Clements, whose wife survived Sandy Hook, the book features writing by poets, activists, lawmakers, and survivors. In its 171 pages, these writers recall tragedies like the murder of 12-year-old Tamir Rice by a police officer and the 2012 shooting in an Aurora, Colorado movie theater. Each poem is followed by a response from a “citizen,” often someone who has experienced a similar tragedy and now works to prevent them. By including this wide range of stories, Bullets into Bells portrays gun violence, which multiple contributors describe as a public health emergency, as a multifaceted issue.

While one might argue such a collection runs the risk of poeticizing violence, of indulging nostalgia for a nonexistent peaceful past, Bullets into Bells succeeds in quite the opposite. Instead of romanticizing suffering, particularly a kind that disproportionately affects marginalized groups, the book’s contributors work to “untangle” and communicate what Colum McCann describes in his introduction as “the intricate nuances of that suffering.”

In “All the Dead Boys Look Like Me,” for example, Christopher Soto grapples with the simplicity of fact. Through long, plain-spoken lines, he considers his resemblance to multiple dead. “Last time I saw myself die,” Soto begins, “is when police killed Jessie Hernandez // A 17-year-old brown queer, who was sleeping in their car.” Here the poet’s use of present tense—is opposed to was—insists on the omnipresence of this trauma. Written in the wake of the shooting at Pulse on June 12, 2016, Soto’s poem also likens his body to those:

Now, on the dancefloor, in the restroom, on the news, in my chest

There are another fifty bodies, that look like mine, and are

Dead. And I have been marching for Black Lives and talking about the police brutality

Against Native communities too, for years now, but this morning

I feel it, I really feel it again. How can we imagine ourselves // We being black native

Today, Brown people // How can we imagine ourselves

When All the Dead Boys Look Like Us?

These resemblances are not coincidence, of course, and this interrogative poem emphasizes the pervasiveness of that truth. “It centers the identity of queer people of color in the face of not just one isolated, horrific and horrifying tragedy,” explained editor Adam Fitzgerald when the poem was first published by Literary Hub, “but in the ongoing history of what Claudia Rankine evokes with her chilling line ‘And still a world begins its furious erasure.’” If the writer’s responsibility is, in the recent words of sam sax, “to hold up a mirror” and “to make strange what we take as baseline reality,” then Soto accomplishes this kind of meaning-making.

Jameson Fitzpatrick’s “A Poem for Pulse” takes a similar approach, making strange the conflicting realities of an uneventful June 12th in New York City and what happened, only hours later, in Orlando. In the poem, the speaker goes to a gay bar with a man he “[loves] a little,” and they wonder together what might happen when or if the place closes. Later, they walk back to his apartment “next to a bar that’s not a gay bar” and kiss goodnight, acutely aware of the “people who aren’t queer people” watching them. “We just call those people, I guess.” Despite the audience, he refuses to feel afraid:

I left

the idea of hate out on the stoop and went inside,

to sleep, early and drunk and happy.

While I slept, a man went to a gay club

with two guns and killed forty-nine people. At least.

Today in an interview, his father said he had been disturbed

by the sight of two men kissing recently.

Originally posted on Facebook, “A Poem for Pulse” was shared widely and picked up by Newsweek. “I was just struck by how small and quotidien the act of two men kissing is, how many times I have participated in it,” Fitzpatrick explained to Newsweek’s Tufayel Ahmed. In other words, his poem attempts to confront the unequivocal, asking “What’s a single kiss?” How does it wield such power?

Like Soto’s and Fitzpatrick’s poems, Ada Limón’s “The Leash” untangles and questions the ways in which trauma infiltrates the everyday. Alluding to environmental degradation as well as the proliferation of hate and hostility in America, the poem portrays gun violence as concurrent with other forms of systemic violence. Through such allusions to “the birthing of bombs of forks” and a river “poisoned / orange and acidic by a coal mine,” even the trucks that come “break-necking” up the street as the speaker walks her dog seem menacing.

Astonishingly, the dog runs toward them. “She thinks she loves them,” Limón explains, “she’s sure, without a doubt, that the loud / roaring things will love her back, her soft small self / alive with desire to share her goddamn enthusiasm.” The dog’s absurd ardor breaks the poem open, inviting the reader to imagine her stupid, canine glee, her owner panicked and jerking the leash. At the beginning of the poem, the speaker wonders what’s left after “the frantic automatic weapons unleashed, / the spray of bullets into a crowd holding hands.” The dog’s indisputable desire offers up an answer.

Bullets into Bells was titled after Martín Espada’s “Heal the Cracks in the Bell of the World,” which references the practice of melting bullets, cannons and other weaponry to make bells. “Now the bells open their mouths of bronze to say: / Listen to the bells a world away,” Espada writes in the poem’s opening. Much like these bells, contributors to this anthology do not sing or chime as much as they announce, their rhythm a reiteration of what we already know. “There is a reason we recite poems at funerals and births and weddings,” McCann writes near the end of his introduction. “This is where life is most fully engaged.” Resisting—or maybe exhausted by—lyricism, these poems instead make room for such engagement, and for the simultaneous plainness and complexity of suffering.