Compensation and Nuance: An Interview with Michele Hutchison

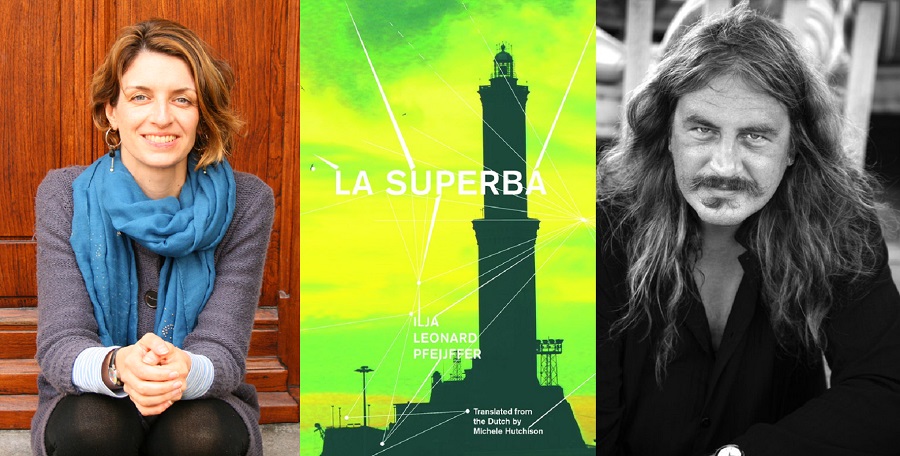

Michele Hutchison is an editor, blogger, and translator of both Dutch and French living in Amsterdam. For this interview, we’re talking about one of her latest projects, La Superba, a novel written by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer recently published in the US by Deep Vellum. Pfeijffer is known in the Netherlands for both his prose and his poetry, and this is the second novel of his that Hutchison has translated. La Superba is a semi-autobiographical account of a Dutch poet living in Genoa. The novel has won multiple awards, including the Libris Literatuur Prijs and the Tzum Prize for most beautiful sentence.

Michele Hutchison is an editor, blogger, and translator of both Dutch and French living in Amsterdam. For this interview, we’re talking about one of her latest projects, La Superba, a novel written by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer recently published in the US by Deep Vellum. Pfeijffer is known in the Netherlands for both his prose and his poetry, and this is the second novel of his that Hutchison has translated. La Superba is a semi-autobiographical account of a Dutch poet living in Genoa. The novel has won multiple awards, including the Libris Literatuur Prijs and the Tzum Prize for most beautiful sentence.

Graham Oliver: Tell me about that Tzum Prize. Did that add some weight when translating? Did you seek out those sentences first, or did you try to keep yourself unaware of which sentences they were?

Michele Hutchison: Yes, I did worry about those sentences and to be honest, I think other sentences in the translation worked out better. So if you were going to look for a Tzum contender in the English edition, I think you’d choose something different. Translation’s always like that—you try to pick up elsewhere what you’ve dropped along the way. To be more explicit, I’m talking about compensation, often discussed in translation circles. I try to compensate by imitating the author’s style where possible. For example, if he’s used alliteration in a passage, I might not be able to replicate it at that exact same point, but I hope to get it in somewhere.

GO: In the book, the protagonist mentions how he’s frequently approached when in his home country of the Netherlands when he’s out in public by people who recognize him. Do you have a sense of how true this is? While we have a few iconic writers in America, I can’t imagine there are many who worry about being recognized every time they go out in public.

MH: Remember that the protagonist is an unreliable narrator who lives in a fantasy world, so everything should be taken with a pinch of salt. That said, it’s actually true that Ilja is a very famous figure in the Netherlands and does frequently get approached in public. He’s a large, striking-looking man so it’s easy to recognize him. Actually, he was primarily known as a poet before he broke out as a novelist with La Superba which won a major prize. It’s hard to imagine, but poetry is a major art form in the Netherlands. Poets are famous here and poetry is well-respected. Ilja has won a lot of prizes for his poetry including a recent grand slam of three awards in a row for his latest collection, Idylls. Add to that a writer who has an amazing stage presence and is a great performer and yes, you’ve got a national celebrity.

I’d like to add that in real life he is quite modest. I’m concerned about Americans not getting the dry Dutch sense of humour in the book. The Dutch are quite self-deprecating and don’t mind having a laugh at their own expense.

GO: A lot of this book is exploring the difference between the southern, Italian way of life that the protagonist is trying to assimilate into, and the northern, Dutch way of life that he comes from. One of my favorite distinctions drawn is that in the Netherlands they drink beer while watching football and at some point the beer becomes more important than the football, whereas in Italy they drink coffee while watching and become almost fanatical. He simultaneously mocks/loves parts of both cultures. As Americans looking in, we might miss some of the nuance presented. What should we pay attention to?

MH: I think Americans tend to lump everything European into a big mixed bag called “Europe” which means history and quaintness and tradition and old buildings. Americans often think the Netherlands is part of Scandinavia, getting it confused with Denmark, but I guess the cultures are similar so we shouldn’t find it as laughable as we do. Northern Europe is cold and wet and dark and it’s a very typical thing to long for a place in the sun—hence the dream of moving to Italy. Italy is to the Netherlands what Spain is to the UK, so we get that sense of longing to move somewhere that is warm and romantic. The USA is so massive you’ve got all those things in the same country.

GO: I have to ask, did it bother you at all that part of this semi-autobiographical novel involves the poet’s German translator throwing herself at him?

MH: That’s a good question. I found it rather hilarious to be honest and laughed out loud as I translated those sections. As you say it’s a semi-autobiographical novel, so part based on actual experiences, part based on fantasy. Where some characters are directly drawn from real life like Don, whom I met when I was there, others are not. The character isn’t a particularly realistic portrayal of a translator, is she? I doubt any translators I know would make such social faux pas as she does when out with Ilja’s Italian friends. We tend to be a little quieter and more observant. So she must be at least part fantasy, right? Part of her function in the story is for her big, blonde Germanic physicality to clash with the dark, elegant fragility of Italian women. The use of dichotomies and the carnivalesque are typical stylistic devices in Ilja’s work. Almost everything is larger than life.

GO: Who else should we be reading from Dutch literature?

MH: I’d like to recommend the wealth of Dutch poetry available in English language translation. Plenty can be found on the English-language website run by Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam.

In terms of recent collections, David Colmer’s fine rendering of Hugo Claus’ poetry in Even Now is a gem (published by Archipelago Books). The same translator has just finished Paul van Ostaijen’s Bezette Stad (Occupied City) which is one of my all-time favourites. It’s a groundbreaking work of Flemish expressionism written in 1921 and has amazing typography. Smokestack Books will be publishing in October 2016.

Dutch children’s literature is world class. Pushkin Press in the UK are doing an excellent job of rediscovering Dutch classics by Annie MG Schmidt and Tonke Dragt. Laura Watkinson’s translation of The Letter for the King by the latter has been picking up a lot of prizes.

And in terms of contemporary Dutch literature, well, I’m afraid Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer is hard to beat. He’s really my writer of choice.

Read about Deep Vellum’s decision to bring La Superba to the US here.