Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse: Emerson and the Search for Reality

The posts in this series, Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse, consider various traditions, ideas, and/or authors in the search for imaginative ways to give voice to our current ecological disaster.

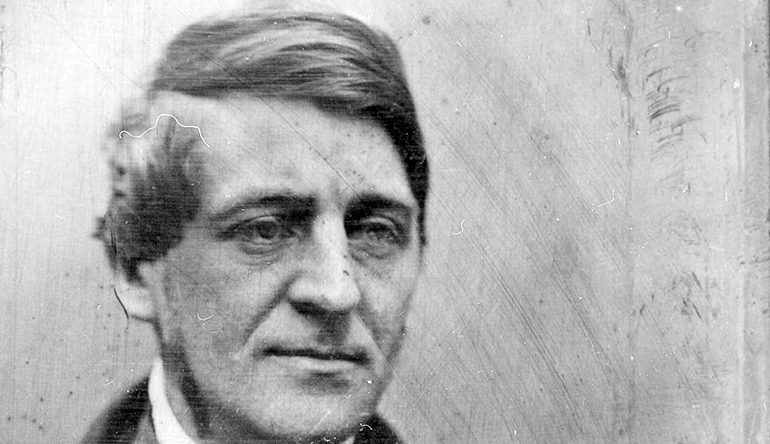

Most of us know Ralph Waldo Emerson as the seer of the individual, a philosopher and essayist who championed nonconformity, blasted social norms, and tasks his readers to dive into the uniqueness of their individual lives and venture forward into unadorned experience.

In one of his typically grandiose statements, Harold Bloom said of Emerson, “From his moment to ours, American authors either are in his tradition, or else in a countertradition originating in opposition to him.” Though Emerson may have served as a font of inspiration for countless minds (such giants as Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman were among his disciples), there remains a widely held opinion that Emerson is little more than a writer of hackneyed inspirational works, with lines like, “Our greatest glory is not in never failing, but in rising up every time we fail,” or “What lies behind you and what lies in front of you, pales in comparison to what lies inside of you,” that belong to the world of greeting cards and graduation speeches, not literature.

But if we cut through the soft, friendly Emerson, we find that for all its optimism and apparent naivety, Emerson’s work is immersed in a mature, tragic vision that asks us to confront the mean aspects of life, the inherent limitations and necessary failures we all must face.

Emerson believed in the individual’s capacity to creatively shape themselves. Through action, risk, and a sort of mental courage that does not rely on the comforts and securities of others or social institutions, individuals can discover the God within and come to realize the full force of their potential. As stirring as his writings on this can be, this inner quest and outer resistance is a lonely and uncertain path that regularly courts delusion. Emerson’s famous doctrine of self-reliance is demanding, for it allows us nothing but our own resources to fall back on, and we are such frail creatures that though we house unlimited potential within, this power is always undermined by our too-human limitations.

Along with his flights of optimism, Emerson recognized that the world owes us nothing, gives nothing in return, mocks our ideals, and, yet, is the reality we must return to and work within. He asks us to be honest, not to hide away in ideals or expectations, to stop crippling ourselves with belief that the world is here to serve us. For all the talk of human potential and ideal power, Emerson, particularly in his later writings, tends to dwell on the disappointments we all must face. In doing so, he crafts a darkly pragmatic vision built within the barriers of fate, the iron laws that bound the world and place the chains of necessity on the wings of possibility.

This is a point of despair as much as it is a source of creative inspiration, for the full energy and power of life is found in taking in and celebrating the whole contradictory mess it offers, especially that necessary, though often avoided, fact that even the most sublime lives must waste away. “Let us build to the Beautiful Necessity,” Emerson writes, as he concludes his great essay, “Fate”:

The Necessity which rudely or softly educates him to the perception that there are no contingencies; that Law rules throughout existence, a Law which is not intelligent but intelligence,—not personal nor impersonal,—it disdains words and passes understanding; it dissolves persons; it vivifies nature; yet solicits the pure in heart to draw on all its omnipotence.

There are perhaps as many Emersons as there are readers of Emerson, and even though it does describe a big chunk of his philosophy, I have always had trouble with labeling his work as “transcendentalist.” Emerson does not want us to be blinded by speculation, he wants sober men who are not suffering an idealist’s hangover. He urges grit in his readers, pushing us to confront the unsavory, the dull, and the unhappy facts that populate so much of our waking hours. The most heavily underlined and annotated pages in my volumes of Emerson are skeptical as they are practical and, if anything, words that temper his more extravagant writings and ideals to this earthly reality we all must collide with.

So, what does this have to do with the literature of climate change?

As we hear people deny climate change, minimize the severe environmental degradation humans have on the world, or simply settle into complacency where they are concerned with the environmental situation but continue to consume and rely on the things that drive climate change, I think there is an imaginative hunger for reality. Reality, as a shout that wakes us from the puerile dreams of how things ought to be. And as we begin to face the consequences of climate change and witness how environmental degradation may impact humans, reality is indeed knocking at the door.

Indications are clear that at some point, maybe not in our lifetime, the great human project of engineering the earth, of colonizing lands, turning an inhospitable world into one capable of sustaining seven, eight, nine, even ten billion people and more, will meet with some sort of reconciliation. The result may be a planet not chemically or atmospherically hospitable to human life.

I do not want to make Emerson into a conservationist or a climate activist. He celebrated the industrial imagination, and plenty of free market capitalists have claimed him as one of their own. What I am interested in is how the drama Emerson saw play out in the life of individuals, that reality will always humble even the greatest and most successful enterprises, may happen on a planetary scale. Bitter though this pill may be, imaginatively, it is a refreshing alternative to the myopic optimism those such as Thomas Friedman and most every TED talk continues to hawk. You know the pitch: technology will fix this or solve problem X, Y, and Z, and human ingenuity, mostly in the form of neuroscience and microchips, will lead to a cleaner, more just, and more equitable world.

What Emerson offers those who want to take an honest and deep look into our troubled relationship with the planet is a kind of negative guidance for the contemporary imagination. It was in that Beautiful Necessity, the physical laws we depend on but that will also crush us, which force the individual to learn that they are subject to a much larger phenomenon than they had the power to imagine, where Emerson believes we may discover the fuller source of energy contained within that elusive phenomenon called reality.

Emerson left fragmented images of this quest for reality, one that is accomplished not through an accumulation of experience or realization of inner potential, but by paring away, reducing our hard-won perspective to a naked truth we can momentarily gleam, but not capture.

Walt Whitman famously wrote, “I was simmering, simmering simmering. Emerson brought me to a boil.” I believe if contemporary writers can look beyond the popular and well-traded image of Emerson as the purveyor of stale inspiration, we may be ready for a darker Emerson to show us that our potential and power is tied to the sublime, though tragic, reality of our times.