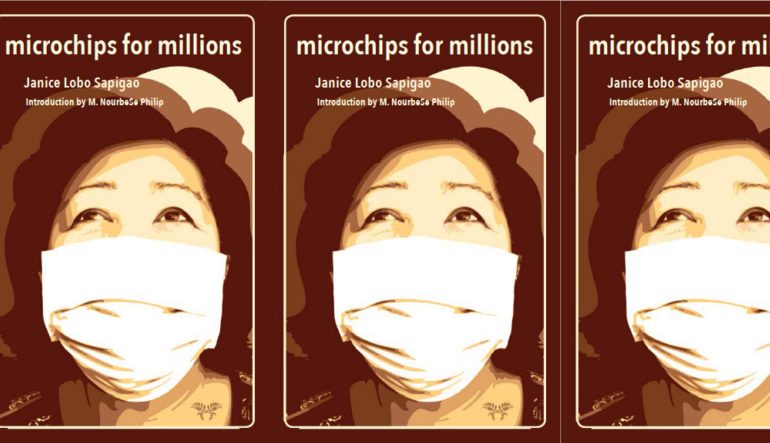

Disrupting Silicon Valley in Janice Lobo Sapigao’s microchips for millions

Disruption is the word in Silicon Valley. Almost every startup promises it: Uber with ride-sharing, TaskRabbit with odd jobs, Bodega with…bodegas. In corporate conversations, “disruption” means innovation, groundbreaking change, a better, cleaner future. It is valued above all else. Which is why there’s a violence to disruption, too—the rapid gentrification of the Bay Area by tech companies, the toxic chemicals contained in phones, the exploitative labor practices that keep corporations afloat. In her debut poetry collection microchips for millions, Janice Lobo Sapigao disrupts Silicon Valley itself, revealing the structural violence that is encoded into it.

In microchips for millions, Sapigao mixes personal memoir with the history of the Bay Area, drawing parallels between colonial and contemporary exploitation. The book opens with a page-long acknowledgement of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe who first lived in the Bay. The “moment of recognition” is followed by a page of binary code, the language composed of zeroes and ones that is used by computer processors, and then ends with another recognition, “Let these pages allow empathy for the immigrant women and their families whose livelihoods are always, always at stake.” The exploitation of immigrant workers, and the gentrification of the Bay Area, are part of a lineage of trauma and theft that have occurred through the years on the land where Silicon Valley is now.

The poems in microchips for millions are multilingual: Sapigao includes English alongside binary code and Ilokano, the language of her Filipino family. She juxtaposes modes of communication, breaking down the meanings of words. In “the clean room” she lists the rigid uniform guidelines that factory workers like her mother must follow whenever they enter the workplace in parallel to quotes from conversations with her mother about work.“1. / hairnet / 2. / shoe covers / 3. / gloves,” is juxtaposed with, “‘they don’t like you / to wear sneakers. / they like you wear / the shoes they give you. / my feet is hurt.’ // ‘it’s hard to breathe, / sometimes. oh my god.’” This is a poetry of political refusal, the voice of immigrant women workers is the one that speaks most loudly, most vividly in this book. The corporate voice of Silicon Valley is left sterile, stripping the farce of its labor practices to their base cruelty: the workers don’t matter, but the microchips they make do. Sapigao quotes official sources, “A clean environment is designed to reduce / the contamination of processes and / materials. This is accomplished by / removing or reducing contamination / sources,” then adds, personally, painfully, “my mother is contaminated.” Behind the wealth, the technological innovation, is the terrible precarity of immigrant women workers—the labor exploitation, the fear of being fired without benefits, of being caught organizing a union.

One poem, “the start-up,” is structured in the shape of the 101, the freeway that traverses the entire state of California. Two black lines in the center of the page filled with binary code mark the freeway, which is lined on either side with boxes filled with text that represent buildings. One side of the freeway chronicles a reality show about Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, and the other shares the history of East Palo Alto, a city left behind by the tech boom. In the corner of the page there is a small note: “map not drawn to cartographic or traumatic scale.” It’s impossible for the page to hold the many histories of trauma that have happened on this land, but Sapigao draws the map anyway.

The whole of Silicon is contaminated, by the tech companies and the toxic fumes that emit from their factories. Sapigao documents this in screenshots of Google maps of the Bay Area that appear in intervals throughout the collection. The maps are layered—one pictures San Jose, the map marked with purple oblongs and dots that indicate chemical plumes. Overlaid in white text, Sapigao has written, “strange leftovers.” Sapigao won’t let Silicon Valley’s leftovers go unmapped. Near the end of the book she asks, “what do we do with / a map?” One answer might be, turn it into a poem. Gather the leftovers, the marginalized stories, and erased voices that have been left off the map, and write them down in a new language.