Do-Overs: 5 Books that Tell The Untold Story

Some of the best rewrites of classic stories come to us through the author’s imaginings of what the original doesn’t say. Through original work that transcends “fan fiction,” these stand-alone novels and plays work best when they have their own story to tell. Whether this is done through expanding narrative summary into scene, giving complicated back stories to villains or flat characters, or imagining the origins of a character’s motivation, these secondary authors work in collaboration with their sources to present a new view.

Some of the best rewrites of classic stories come to us through the author’s imaginings of what the original doesn’t say. Through original work that transcends “fan fiction,” these stand-alone novels and plays work best when they have their own story to tell. Whether this is done through expanding narrative summary into scene, giving complicated back stories to villains or flat characters, or imagining the origins of a character’s motivation, these secondary authors work in collaboration with their sources to present a new view.

Here is a list of several works that fill in the gaps left by the originals:

- March by Geraldine Brooks | Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

March imagines the life of the mysterious absentee father of Alcott’s classic tale. In part, Brooks bases her version of the March family patriarch on Alcott’s father. March fights for the Union in the Civil War, often choosing not to reveal the horror of battle in the letters he writes home. In her Washington Post review of March, Karen Joy Fowler notes how “The Alcott book and characters have floated like ghosts all through March. That story of scorched gowns, amateur theatricals, pickled limes, balls and picnics and pianos provides a wonderfully effected, unstated but understood contrast to this story of the war.”

- Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal by Christopher Moore | The New Testament

At first glance, Moore’s Lamb seems like little more than a gleefully blasphemous romp through the New Testament. But as he said in an interview with Christianity Today, the author spent countless hours working with his source material to establish a cogent timeline of events so he could work Biff and some colorful commentary into the life of Jesus.

“What I wanted to do,” Moore says, “was show the ‘behind the scenes’ aspect of the gospels, without boring people with a lengthy retelling of a story they already knew. So, where in the gospels there’s one line about how Jesus cast seven demons out of Mary Magdalene, in Lamb you see that happen. I wanted the effect to be additive, hopefully enriching the experience of the story with humor, while giving those familiar with the gospels a sense of discovery: ‘Oh, that’s the way it might have happened.’”

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard | The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark by William Shakespeare

Yeah, everything goes back to Hamlet. But this classic play that imagines the confusion of Hamlet’s friends who aren’t privy to the main action of the play is Stoppard’s way of having fun with the original while still echoing its existential questions.

- Finn by Jon Clinch | Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Jon Clinch’s 2007 backstory for Pap Finn takes Mark Twain’s original tale and strips away any niceties Twain relied on as he composed his tale for children. Twain famously complained about the constraints of writing for young readers, and Clinch seizes the opportunity to paint Pap as a complicated, tragic figure. Does it work? While Finn has many fans, Ron Powers, in his New York Times review of the work said, “Working from [the] compost [of Twain’s original], Clinch transports Pap Finn to a parallel universe; and this universe diminishes ‘Finn.’” But whether we accept Pap as a character is less important than Clinch’s goal: ultimately, with his work he furthers Twain’s and creates his own world.

“Poor Grendel’s had an accident,” the famous, hapless monster muses. “So may you all.” Perhaps the best known of the “villain’s story” genre, Grendel is often admired for how Gardner handles his source. The author spoke of his fondness for inspired work in an interview quoted by the Paris Review:

“When you tell the story of Grendel, or Jason and Medeia, you’ve got to end it the way the story ends— traditionally, but you can get to do it in your own way. The result is that the writer comes to understand things about the modern world in light of the history of human consciousness; he understands it a little more deeply, and has a lot more fun writing it.”

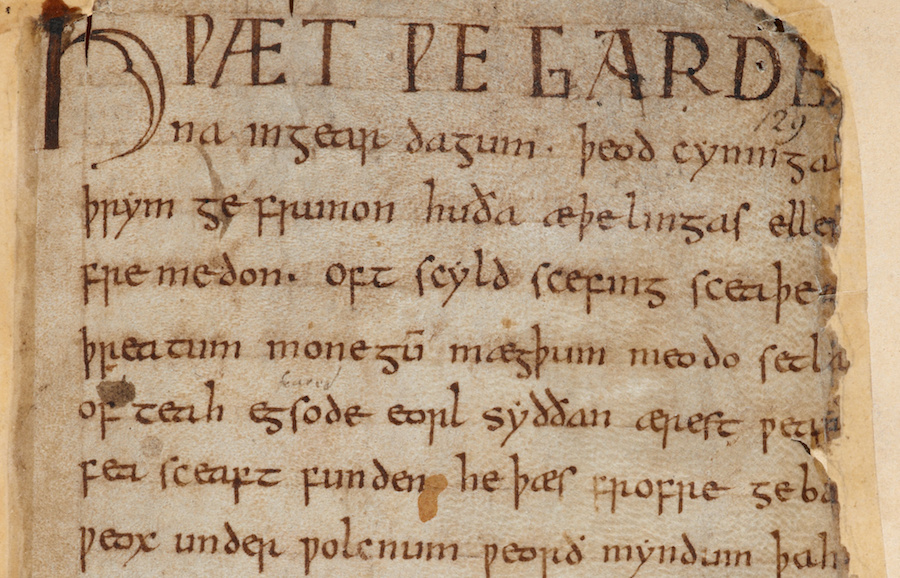

image: The Nowell Codex (Beowulf Manuscript), located at The British Library