Exaggeration & Distortion: What Writers Can Learn From Visual Artists

The purpose of art is not to depict reality—it is to transform reality into something more interesting and meaningful. And the only way to do this is to distort, exaggerate, or in some way embellish what is there.

Supernormal stimuli excites us more than reality does. Birds, mammals, fish, all human beings and at least some arthropods exhibit heighten emotional response to exaggeration.

This phenomenon, known as the “peak shift effect,” originated with the discovery by scientist Niko Tinbergen that herring gull chicks will tap the red spot on the beak of their mother when they want to be fed; expose the chicks to a fake beak with multiple red dots and their rate of pecking increases proportionally. A shift of stimuli towards exaggeration peaks the effect.

Neuroscientist Vilayanur Ramachandran, director of the Center for Brain and Cognition at the University of California at San Diego has theorized that visual artists instinctually know how to employ the peak shift effect. The exaggerated female form in ancient fertility statues, suggests that this instinct in artists is ancestral.

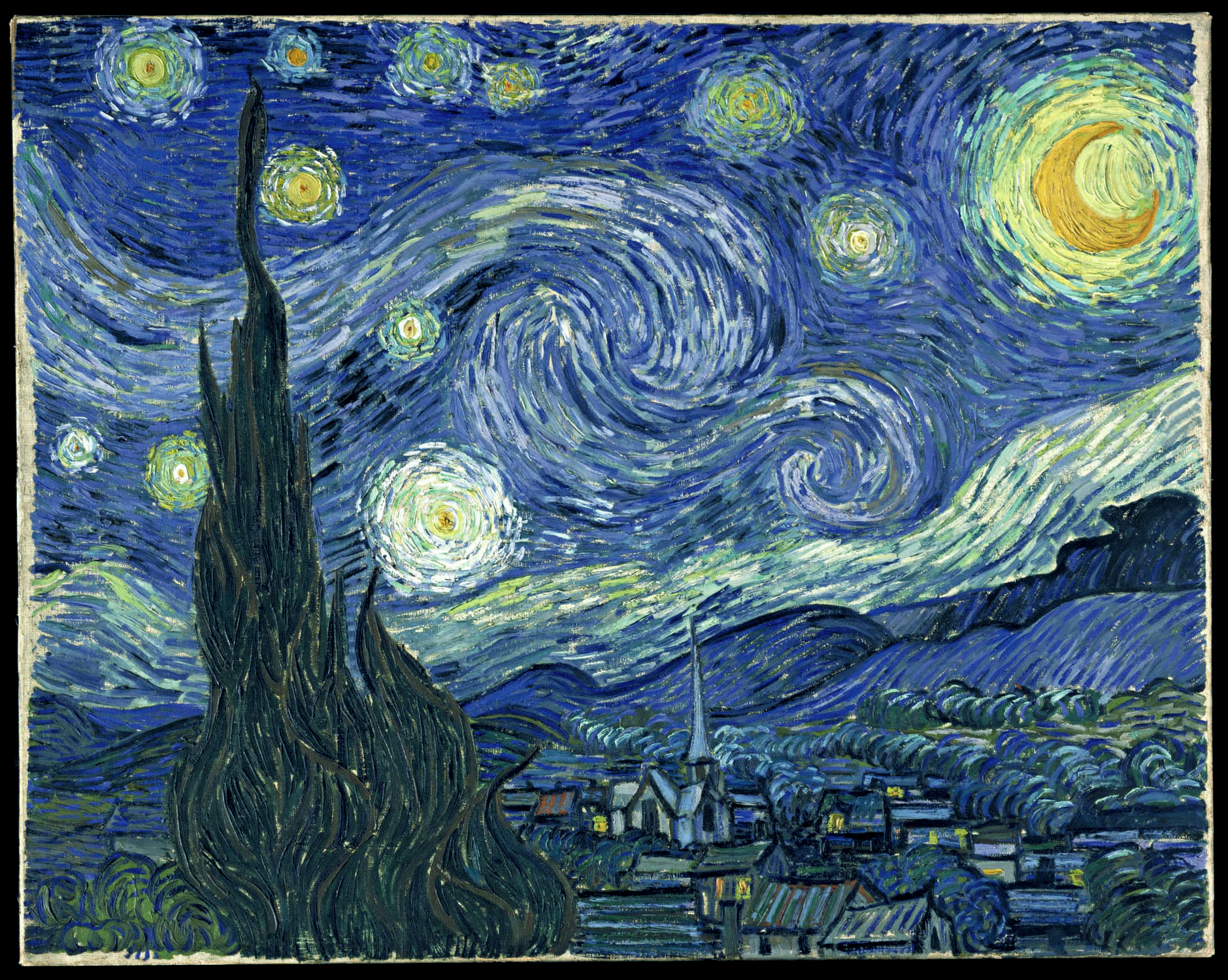

Skilled artists know how to capture the nature of their subjects by amplifying the qualities that make that subject distinct or noteworthy. Caricature artists are masters at this. Studies have shown that we can recognize visual parodies of people more readily than we recognize photographs of them. An experienced painter knows how to use exaggeration to evoke the desired response. To capture a downtrodden, pleading mood, a painter might overstate the droop of the lower lids and redness around the rim. Landscape painters often choose one or two details to highlight. For example the white of shimmering moonlight on the ocean or the yellow of the sun grazing the tops of the trees. In Vincent Van Gogh’s starry night, his exaggeration of color and movement is so emotionally powerful it’s nearly impossible to stand in front of it and not weep.

The painter Alice Neel is known for her use of exaggerated line. She employs it very specifically to draw your eye and make you feel. Picasso chose to exaggerate by flattening perspective and quite literally cubing the human form. Cubism, surrealism, hyperrealism, impressionism, expressionism, virtually all movements in art are rooted in distinct forms of exaggeration. All art forms are a type of exaggeration. Music is an exaggeration of sound, dance, an exaggeration of movement, and great-story telling relies on embellishment. Writers should not shy away from using it as lavishly as artists do.

Reality can be tedious. Day to day life often consists in large part of mundane tasks and superficial conversation. The larger, more dramatic events in life seem random. In the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Everything in the universe goes by indirection.”

When I write a scene, I distort reality as a painter does. I decide first how I want my world to be understood. What is it that I want my readers to feel and see clearly? Then I’ll look around at my setting and ask myself: What’s here that I can use? If there is light coming in the room, I’ll accentuate it to set the mood. If there’s a couch, I might heighten my readers awareness of how it’s worn. And I will study my characters’ faces. Is there a specific feature I can exaggerate to make the reader understand who they are more clearly? And how can I dramatize or embellish what my characters do and say? I will pick and choose and manipulate the essential elements of my scene until I’ve reshaped reality into a new form, one that holds together and sheds an unexpected light.

Picasso once said, “Art is the lie that reveals the truth.” Skillfully told, the lie can elicit an epiphany.