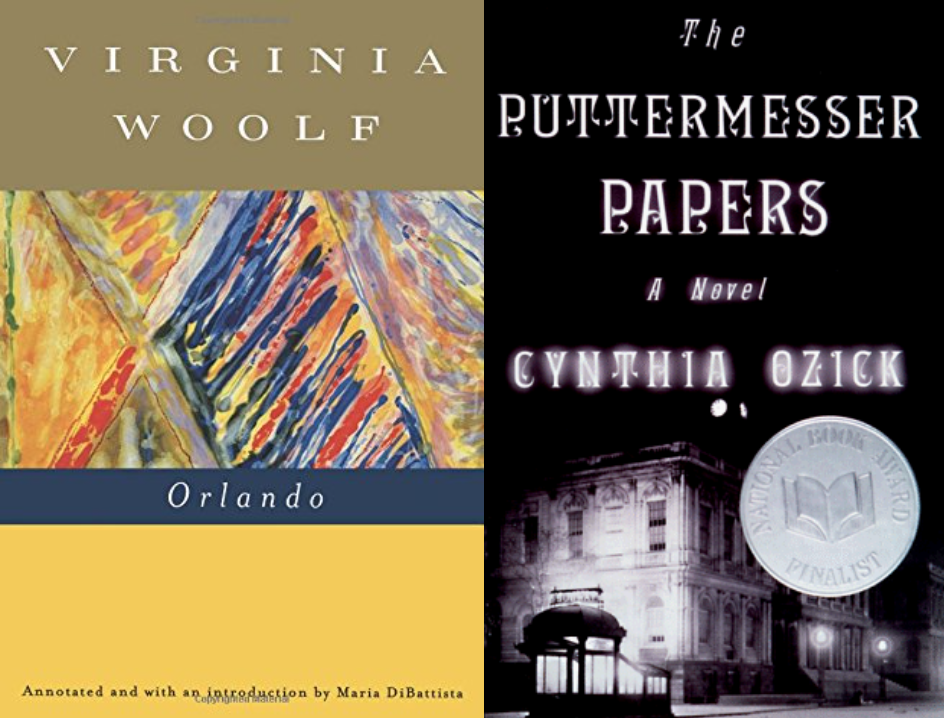

Exploring the Self in Orlando and The Puttermesser Papers

Over the past couple of years I’ve found myself drawn to novels, often by women, that explore selfhood—as well as friendship, marriage, art-making, and motherhood—through a self-reflexive, autofictional first-person voice. Books like Rachel Cusk’s Outline, Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, and Nicole Krauss’ Forest Dark explore the self through a ruminative first-person and are structurally focused on everyday episodes that resonate over the course of many years. Recently, though, I’ve also begun to reread two zany, sprawling, somewhat manically-narrated novels that first shaped my understanding of the vast and various ways to write about the self—and how the self relates to gender, history, and work. Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, published in 1928, and Cynthia Ozick’s 1997 novel The Puttermesser Papers are both comic, picaresque mock-biographies of brainy, somewhat eccentric characters. Both stories show a disregard for strict realism, the protagonists of each flaunt societal gender-based expectations like marriage and children, and both narratives are insistently funny, peppered with metafictional nods to the reader and side commentaries on the nature of writing. They’re expansive and kinetic books. The protagonists’ adventures and misadventures are romp-like tours of female agency, freedom, and the exhilaration of making one’s own way in the world.

Orlando, which is dedicated to Woolf’s lover and friend Vita Sackville-West, follows its title character over the course of his three hundred year lifespan. Orlando, whose character is modeled off Sackville-West, is born a man during England’s Elizabethan period who, after some adventures and love affairs, wakes up and finds he’s been transformed into a woman. Orlando then passes through the centuries, her life intersecting with the literary history of England in various ways. The writing is as playful as the story, and the story is as much one about the difficulty of pinning a character on the page as it is about Orlando in particular. One of the purposes, it seems, of Woolf’s deathless, childless, fluidly-gendered protagonist is that Orlando never runs out of time to think—she is never pushed to the margins. Woolf has allowed her protagonist to take up a superhuman amount of space in a form, the biography, which was originally designed to venerate supposedly Great Men. Orlando’s impact on history is unclear, but she’s mesmerizing—Woolf uses the book to question whose stories we allow space on the shelf. Orlando, without the pressure of time and death, can linger. In an early chapter Orlando muses about fame and obscurity, and then “stretching his limbs out under the oak tree”—a tree which will give Orlando’s book, a project that follows him over the centuries, its title—Orlando has the following realization:

Rid of the heart-burn of rejected love, and of vanity rebuked, and all the other stings and pricks which the nettle-bed of life had burnt upon him when ambitious of fame, but could no longer inflict upon one careless of glory, he opened his eyes, which had been wide open all the time, but had seen only thoughts, and saw, lying in the hollow beneath him, his house.

The payoff of all the wandering and Orlando’s many picaresque adventures, it seems, is this sort of presence—indeed, the novel ends with Orlando, now a woman, again under the oak tree, contemplating the relationship between poetry and fame. Orlando earns sight, and insight, through motion and experimentation.

Cynthia Ozick’s protagonist, Ruth Puttermesser, doesn’t have the luxury of immortality. Her world isn’t Elizabethan, then Victorian, then modern England; rather, the book opens when she’s a young law school graduate working in the “Municipal Building” in her native New York. Like Orlando, she has various affairs; like Orlando, she remains childless; like Orlando, she’s intelligent and has a life’s work.

The book is divided into five sections. In my favorite, “Puttermesser and Xanthippe,” Ruth Puttermesser accidentally constructs a golem from the soil of her houseplants. The golem looks like a woman, and though, as in Jewish folklore, she’s designed to obey Ruth, she still insists on being called Xanthippe, rather than Leah (the name Ruth wants to give her). Ruth isn’t particularly excited by the idea of this pseudo-motherhood, but rather what it says about her intellect. She muses, after reading extensively about golems:

What interested Puttermesser was something else: it was the plain fact that the golem-makers were neither visionaries nor magicians nor sorcerers. They were neither fantasists not fabulists nor poets. They were, by and large, scientific realists—and, in nearly every case at hand, serious scholars and intellectuals.

Xanthippe will ultimately bring Puttermesser both success and destruction—as in Orlando, Ozick reminds the reader that fame and success can often obfuscate true purpose. But, like Woolf, Ozick gives her protagonist the space on the page to fully inhabit her successes and her downfalls—we never get the sense that Ruth’s missing out on life, but rather that she’s often at its churning, if sometimes ridiculous, center.

I’m struck by the epigraph to The Puttermesser Papers, which Ozick attributes to a Dr. Enid Starkie “disapprovingly” cited in Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot:

Flaubert does not build up his characters, as did Balzac, by objective, external description; in fact, so careless is he of their outward appearance that on one occasion he gives Emma brown eyes; on another deep black eyes; and on another blue eyes.

Ozick has re-spun the “disapproving” quotation as a kind of manifesto: this is a novel about the flights and fancies of an intellect, and rather than this being a detriment to our understanding of Puttermesser, it helps us understand her character at its deepest level. Orlando, too, is ultimately about a character’s mind. The picaresque humor of these novels, along with the occasional disembodiment of their protagonists, allows for exciting studies in the freedom of thought—and the powerful impact intellect can have on the physical world.