Faith and Sycamore

The richest and weirdest secret my five-year-old daughter has involves a tree on her school’s playground she calls “Rosey Treezy,” her “favorite tree,” she says. She tells me she “protects the tree and won’t let anything happen to it,” that she huddles around it with two of her friends during recess. “Then you three,” I say, “are the Guardians of the Tree,” and just like that, a new faith is born.

She draws Rosey Treezy all the time—a squat brown trunk with a green crown, a rainbow above it, three figures in triangle dresses and puffed sleeves below it: a religious icon.

Sometimes I imagine that with my daughter’s crayons I might draw a timeline. On it I’d make little wax hashmarks for the moment nature-worship became patriarchy-worship and when religious art began to secularize. But then my timeline would grow messy, grow limbs, show overlapping dates, parallel marks, and perpendicular ones, marks branching off in all directions—to suggest our sense of mystery, of the sacred, hasn’t really changed, only been layered over, circled back to, revisited at certain moments in time. In fact, it might begin to look like a tree.

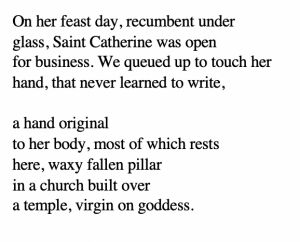

In her poem “Santa Caterina’s Tomb,” Kathy Fagan writes,

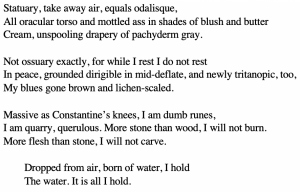

Earlier, she describes a similarly prone sycamore tree, felled and cut in “Sycamore Stacked in Lengths & Pieces”:

Words like “statuary,” “odalisque,” and “torso,” evoke the sculptor’s studio, probe the aesthetic and economic value of a tree robbed of its height, laid low, changed in shape for the sake of something else—art or commerce or love. In “Santa Caterina’s Tomb,” Saint Catherine’s bones retain a kind of glamor codified by the Catholic Church, though we imagine the Church remains willfully ignorant of the older goddess buried beneath her, while perhaps even deeper still lies Sycamore who emblematically belongs to the speaker and who is, so often, emblematic of perseverance and resurrection. This is not, the poem tell us, the work of Fra Angelico who painted “the miracle of blood / sacrifice again and again,” but the manifestation of something far older, something wordless, and therefore easy to speak for, to speak over, to subjugate.

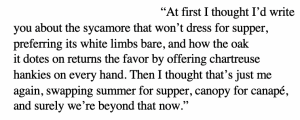

It is up to the sycamore to speak for herself. I say herself because Fagan’s newest collection, Sycamore (Milkweed, 2017), leans on its eponymous tree’s multi-colored, mottled trunks, its hefty size and spreading canopy, to provide a material figure for perseverance and resurrection, replacing those old images of “angel / wings of gold and mica.” What’s fascinating about Fagan’s sycamore is how it’s presented from a multitude of angles, becoming prismatic in its resistance to easy answers or platitudes, remaining unstable despite its apparent stability—it is a tree, after all.

But the sycamore isn’t only a symbol or heraldic device. It’s a compatriot, pet name, secret friend. In the book’s first poem, “Caro Nome,” the speaker establishes her affinity with the sycamore, her “dear name”: “I am the color of that tree / she loves and nearly as still,” a kinship begun by simple association that grows from a partner’s nickname for the speaker into something “metaphorical yet concrete,” even an object of worship.

If religion is a method of narrating mystery, of giving it shape, a face, a character, a name, then Sycamore is a backyard goddess. Yes, Sycamore is a deeply religious book. I can’t say spiritual—which may be the softer word, the less polarizing one. I say religious because in their own, diffident way, the poems in Sycamore mean to seriously question power structures that would shore up environmental exploitation and inflict cruelty. They are both in love with religion’s trappings and skeptical of them. They look for traces of ritual and tradition in unusual places, and find the goddess under the saint.

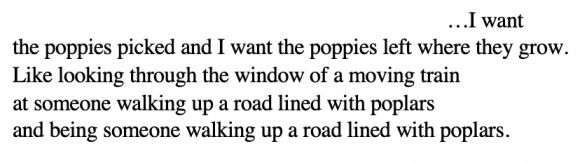

In “Suburban Canticle,” Fagan writes, “The Global Fellowship of Future Saints runs in soccer socks on Razor scooters. / Fireflies light the night for you, saith the Lord, and you shall have dominion / over all the creatures you spy with your little eye as you lie / on your back watching clouds float by.” The conflation of religiosity, childish games, and monorhyme works to undercut the seriousness of Francesco’s “offal perfume, all five wounds seeping and your blind eyes tearing / in the sun.” The saint to whom the speaker is addressing and who is transformed by contemporary American life into a lawn statue “spotted with birdlime among / the mounds of daylilies” is the old-world saint to whom Sycamore confesses, “I, too, was a child among gas mowers, picking warm tar from my foot soles. / The blades of the rotary fan reflected my days like a flip-book. / I was devout for such a long time, but wore my summer clothes and walked / barefoot on the bees and their clover so briefly.” Maybe what the poem’s speaker is asking for here is a new object of devotion or—rather—that object has already arrived in the guise of suburban joys and childhood’s golden haze. But the poem ends, “Let me be clear: / If I pray to you on my knees under the sycamore, I am asking you to let us stay. / Like the honeysuckle, we love it here. We don’t care who we crowd out.” Honeysuckle is invasive and the speaker is conflicted: “we love it here,” but, as the speaker tells us in “Perpendicular,”

The trouble with faith is that it requires faith. The trouble with being alive is that it requires living. For the young, perhaps, these contradictions are less cumbersome, though “Middle-Aged Sycamore” is “only more grateful, if weary of the gratitude / it takes to feel alive.” As Sycamore matures, its capacity for contrast and incongruity grows—think of the multi-colored bark, its empty branches in winter. Language, too, is rife with mystery, prone to inaccuracies, misdirection, misunderstandings. It is the flawed material with which we name ourselves and the world around us.

Throughout Sycamore, there is a growing sense that word games—homonyms, puns, mis-readings, translations—are, like religious ritual, beautiful, colorful, rich in material, but in danger of turning hollow; the misunderstandings are bound to finally add up. “Kaboom Pantoum,” for example, is a poem whose very form lends itself to iterations and playful re-articulations, warning us that, “maybe more than last words / word games reveal a lot—.” She writes: “sequoia, for example, is / the shortest word to use each vowel once. / Word games reveal a lot. / Short word. Tall tree. AEIOU.” In “Letter to What’s Mostly Missing,” Fagan writes:

Language is inaccurate, deeply imperfect, much in the same way the sycamore’s perceived emptiness should be reconsidered. In “Letter to What’s Mostly Missing,” Fagan writes, “The old ones / are nearly hollow, therefore unstable. The fox and rabbit / like to make their dens inside. Empty isn’t always / the opposite of perfectly full.” Silent isn’t always the opposite of perfectly loquacious either; though the sycamore appears mute in winter, she tells us in the poem “Diagnosis,” “Either way, my leaves fell. / And it took a good while, but I grew new / ones. Then the birds came back.”