Fiction Responding to Fiction: Jamaica Kincaid and John Keene (and Edgar Degas)

The Fiction Responding to Fiction series considers the influence that a short story has on another writer; all entries can be found here.

Jamaica Kincaid’s classic story “Girl,” first published in The New Yorker in 1978, is a small gem, consisting of less than 700 perfectly chosen words. It seems to belong to that space between short fiction and prose poetry; its lines ebb and flow, the language propelling the piece forward. Comprised of one long sentence, the story is largely advice from a mother to a daughter. The story begins generally but quickly narrows its focus on the girl to whom the advice is being given:

…soak salt fish overnight before you cook it; is it true that you sing benna in Sunday school?; always eat your food in such a way that it won’t turn someone else’s stomach; on Sundays try to talk like a lady and not like the slut you are so bent on becoming; don’t sing benna in Sunday school;…

The piece continues in this manner, juxtaposing different types of advice. At only two times in the narrative does the girl’s voice break through. The story’s focus is on gender, although race and class are integrally woven in as well.

One of the most anthologized stories of the late 20th century and a staple of freshman composition courses, Kincaid’s story has prompted a number of responses, including “Boy” by Bret Anthony Johnston. Up until now, most of the stories that have been analyzed in this series have had connections that are clear and apparent, intended as such by the writer. Here, though, we will look at a story that was not deliberately written to respond to “Girl” and yet the echoes and reflections are there. The story, “Acrobatique” by John Keene, is included in Counternarratives, published in 2015. Consisting of short stories as well as novellas, the book interrogates history and gives voice to those whose stories have not yet been told.

As with Kincaid, Keene’s language—he is a poet, at his heart—is lyrical and beautiful, and his desire to reframe history important and meaningful. (You can hear Keene read a bit of the story here; read an interesting interview with him about the book in Cosmonauts Avenue here; and listen to an interview/performance on WNYC here.) The book, which recently won a 2016 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, is a collection of many voices woven together in an intricate and skillful manner. While “Acrobatique” was not written to respond to “Girl,” Keene has remarked that Kincaid’s voice is often in his head.

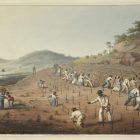

And as with “Girl,” “Acrobatique” is one long sentence. Here, the story represents the thoughts of a historical woman, a circus performer called Miss LaLa. It is ekphrastic, based on an 1879 painting by Edgar Degas entitled Miss LaLa at the Cirque Fernando which is in the collection of The National Gallery in London; the painting is one of Degas’ most famous and yet the only painting that he did of the circus and one of only two that features black figures. Miss LaLa was a famous mixed race circus performer, born in Prussia, to a black father and a white mother. Interestingly, Degas’ relatives in New Orleans were mixed race. In the painting, Miss LaLa is captured high in the air, her face averted, suspended by the rope in her mouth. Needless to say, she is unable to speak, given the rope, and Degas places her body against a rigid, architectural background.

Keene’s story allows us to get into the head of this famous and yet unknowable woman. Her thoughts pour out of her in a stream-of-consciousness, uninterrupted by terminal punctuation, gorgeous words that remind us of her flight:

…plus haut! the voice I can easily discern, it’s the ringmaster’s, the crowd’s, the words, now a lone one in my head, höher, repeating, fleet and fluttering, soaring past me up into the rafters, scattering among the trusses, vaulted arches, the cupola, clambering amid the bats and the blackbirds, across the brickwork seen only by its masons and ghosts…

We learn of her life, of her family, of her friendship with her acrobatic partner, of life in the circus and, finally, of her connection with Degas, the man who would make her body famous to the world. As with Kincaid’s story, race and gender are at the heart of this piece.

One of the fascinating formal components of Keene’s story is that the beginning and end are represented on the page by letters descending vertically, to mimic the rope on which Miss LaLa hangs. The first words in the story are

H

i

g

h

e

r

,

I

h

e

a

r

f

r

o

m

and the final words are

D

e

g

a

s

,

l

e

b

l

a

n

c

,

d

o

w

n

t

h

e

r

e

.

It is, of course, almost impossible to look at the painting without thinking of a lynching, and Keene’s decision to formally present the narrative in this manner underscores that impression.

In “Acrobatique,” while all the thoughts belong to Miss LaLa, there are moments when her mother’s voice takes over the narrative. This feels strikingly similar to the way in which the girl’s voice appears in Kincaid’s story. We know, with Kincaid, when the girl’s voice interjects because those lines are in italics. The girl is pushing back against the onslaught of her mother’s accusations and instructions: “but I don’t sing benna on Sundays at all and never in Sunday school” and “but what if the baker won’t let me feel the bread?”

In Keene’s story, Miss LaLa’s mother emerges in excerpts from her letters, always providing cautionary advice to her daughter:

…but no, Mummi—since Vati has only ever penned one letter I recall—never repeats any of this, instead writing The night, especially in the city is the Devil’s playground and A groshen set aside keeps you out of the almshouse and Remember that not only an accordion makes a pretty song and Don’t forget your family and your Prussian, though how could I, whenever I hear that accent I pause to remind myself where I am…

We can see the echoes of Kincaid in Keene’s work even though the story was not written intentionally to respond. Interestingly, reading “Acrobatique” can also shed a different light on “Girl.” It is possible to read “Girl” as though it is narrated by the mother; it is also possible to see the story as the thoughts of a girl, unable to speak, as she considers how to navigate a world constricted by her gender and her race.

Image: Degas, Edgar. Miss LaLa at the Cirque Fernando. 1879. The National Gallery, London.