Five Books That Changed How I Think About Writing

The best books I’ve read haven’t just been good: they’ve changed the way I think about writing, they’ve challenged what I think a book can and should do, they’ve encouraged me to go back to older texts and read them in a new light. In short, they’ve not only provided me with entertainment, but tools with which to explore the world, tools I can bring to bear on my own writing. Good writing, after all, starts with good reading, and here are five contemporary reads I’d count among the best I’ve come across.

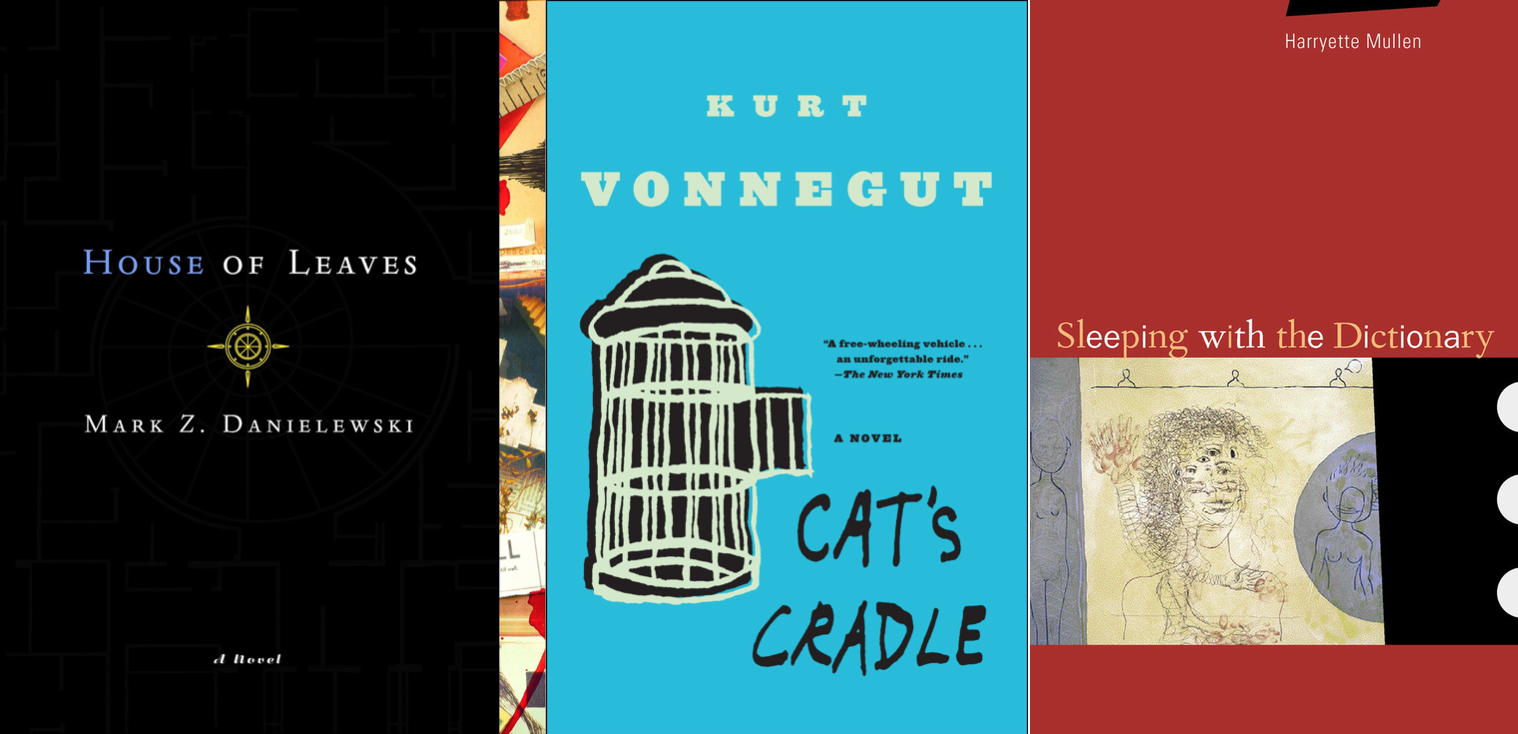

1. Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

This is probably my favorite book of all time. I’ve read it over a dozen times, and each time I pick it up again I find something new to appreciate. The first time I read it, at fifteen, I sat down for the evening and didn’t get up until I’d finished the whole thing, and that was the first time I can remember doing that with a novel. It had everything: war, religion, grief, loss, joy, creation, destruction. And ice-nine! What an invention!

This book proved to me that science fiction and literary fiction could succeed hand in hand and that great writing and great plotting didn’t need to be mutually exclusive. It proved to me that you could write a short book with short chapters and say more than those who had written thousands more words across hundreds more pages.

My favorite lines: “Tiger got to hunt, bird got to fly; Man got to sit and wonder, ‘Why, why, why?’ Tiger got to sleep, bird got to land; Man got to tell himself he understand.”

2. The Girl in the Flammable Skirt by Aimee Bender

I think I come back to these short stories more than any others when I get stuck in my poetry. The images, the ideas, the surreal turns of events, are stunning; to borrow from Coleridge, “that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith” is complete here. Bender’s stories are—to me, at least—enormous poems, and I’m always amazed by the bridging between prose and poetry that manifests itself in her work.

My favorite story from this collection: “The Rememberer,” hands down.

3. House of Leaves by Mark Danielewski

I read this book in college. It so thoroughly took over my life that I stopped going to class for a week so I could read it. House of Leaves blew me away with its structural innovation—this book is in a league of its own when it comes to narrative and typographical idiosyncrasy.

The most succinct summary I can offer is that the book is the purported edited manuscript of a heavily annotated found transcript of a documentary about a supernatural house (say that five times fast). House of Leaves is written in a number of different fonts (some editions include multiple colors), some pages are packed to the margin with text and others are almost blank, some passages appear backward and can only be read in a mirror, some footnotes reference real-life texts, others reference imagined texts, and others reference sections of text or other footnotes that simply do not exist.

To be honest, I had no idea before I read House of Leaves that a book could be so engrossing, so nightmarish (I had weird dreams for months)—I thought only cinema had that power. It comes with my highest recommendation, but I’d advise you not to read it alone or shortly before going to bed.

4. Another Republic by Charles Simic and Mark Strand (eds.)

I’ve only recently been introduced to this text, but it puts so many of my influences under the same literary roof that I’ve already adopted it as a mainstay. Simic and Strand note in the introduction the eclectic nature of the anthology, the disparateness of the authors it draws together, but I’ve found that whatever force drew the editors to these works has drawn me to them, as well. Zbigniew Herbert, Yehuda Amichai, Czeslaw Milosz, Miroslav Holub, Paul Celan, and Italo Calvino have all found their way into my work in one way or another, and I was convinced until recently that their mixture was unique to my own aesthetic; I’m amazed that they could all be assembled—were assembled—by Simic and Strand a decade before I was even born.

5. Sleeping with the Dictionary by Harryette Mullen

(Re)appropriation is the theme of this collection, and the poems here are wonderfully apt and inventive in that pursuit. Mullen riffs on Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, incorporates acrostic acrobatics and surrealist Oulipo techniques, and manipulates the hypercapitalist language of advertising copy into politically motivated poetry to achieve a subtle, incisive wit that often belies the seriousness of her project. Until I read this book, I’d never deeply thought about the raw material of language, its available (re)uses, its many valences and points of interconnection, and ever since my eye and ear have been permanently (at)tuned to the lower frequencies in poetry: connotation, mondegreen, homophone, tone.

Favorite poems: “All She Wrote,” “Elliptical,” “Bilingual Instructions,” and if you read nothing else in this book, make sure you get to “We Are Not Responsible.” You won’t forget it.