Hearing Voices: Women Versing Life presents Tarfia Faizullah and the Unpublished Manuscript

The work of getting a manuscript published, that rejection and frustration, begins to feel at times like self abuse. Writing is a lonely adventure, but most of us feel driven to it; quitting is inconceivable. Submitting work, though, is more like managing a business, and most poets I know are not business managers, so it’s easy for us to get bogged down in the nays.

Maybe in addition to writing workshops, we should join rejection workshops to be reminded that we’re not alone. Because we’re not alone.

In lieu of a rejection workshop I offer you the camaraderie of Tarfia Faizullah.

I read Faizullah’s poem, “Dhaka Nocturne,” in New Ohio Review. It opens: “I admit that when the falling hour/begins to husk the sky free of its/ saffroning light, I reach for anyone,” and from there it becomes an eerie, beautiful mingling of the sensual and the grief-stricken.

After reading “Dhaka Nocturne,” I searched for Faizullah’s book. When I didn’t find one, I read her poems on the Internet (all stunning) and emailed her. I was thrilled when she agreed to chat about her as yet unpublished manuscript, Seam.

PC: Tell me about your manuscript.

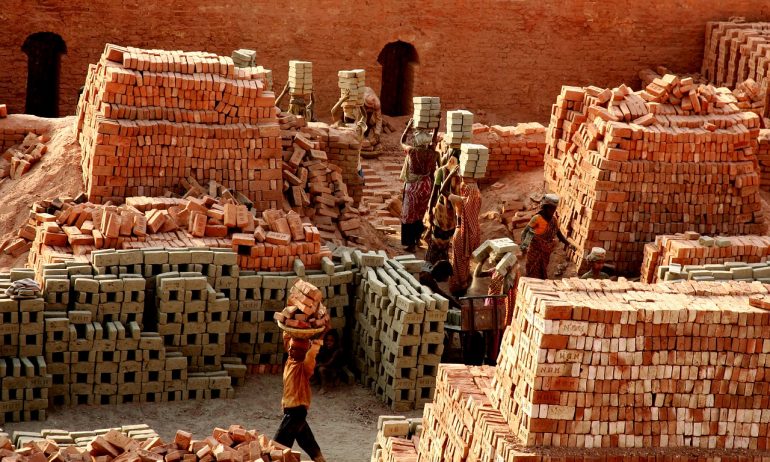

TF: Seam centers around a long sequence of poems entitled “Interview with a Birangona,” which imagines conversations between a Bangladeshi-American interviewer and a birangona (war heroine), a Bangladeshi woman raped by Pakistani soldiers during the 1971 Liberation War. The sequence is bookended by more personal poems that attempt to enact and interrogate not only my background as a Bangladeshi-American, but also the complexities of memory, witnessing, and grief.

PC: Has it always had the same title?

TF: Titles can be such powerful frames for poems, thereby making the titling of a manuscript all the more daunting. The manuscript went through a couple of titles before becoming Seam. The original title was Interview with a Birangona, which eventually seemed redundant since the sequence was already a large part of the manuscript. Heroine was the next working title, but I grew uncomfortable with the implication that the interviewer herself was a heroine.

My friend Amanda Abel suggested Seam after reading a recent version of the manuscript. I appreciate how simple yet nuanced “seam” is: it’s a one-syllable word that can be defined as a line of junction formed by sewing together two pieces of fabric, a scar, or a band of smooth river water that appears when currents of differing speeds meet. All three definitions of seam repeat throughout the manuscript.

PC: When did you begin writing it?

TF: I began writing poems toward the “Interview with a Birangona” sequence in 2007 during my second year of graduate school at Virginia Commonwealth University. A large portion of what ended up in the manuscript I wrote during my year in Bangladesh from 2010 to 2011, including more personal poems such as “Dhaka Nocturne.” Other poems, such as “Reading Willa Cather in Bangladesh” and “Reading Transtromer in Bangladesh” I wrote during or after visits with my family to Bangladesh between 2007 and 2010.

PC: What inspires you?

TF: Lately I’ve returned to Fanny Howe’s consideration of “bewilderment as a poetics and an ethics . . . bewilderment as a way of entering the day as much as the work.” Her invocation of the Muslim prayer “Lord, increase my bewilderment” in the same essay reminds me that a poem can and perhaps should encompass the wilderness as much as act as the compass out of the wilderness.

PC: Are you ever-tinkering with your manuscript?

TF: Absolutely. Over the course of the past year, Seam has undergone multiple revisions: some radical, others microscopic. I’ve continued to work on both individual poems while reevaluating the overall shape and scope of the project. Each time I do, Seam feels stronger, surer, sharper. I do worry that some of the revisions do more damage than good. To borrow from Adrienne Rich, I don’t want to mistake “the story of the wreck” for “the wreck” itself.

Other days I think I am closer to what Jean Valentine might have meant in her poem “The Pen”: “And this pen its thought//lying on the thought of the table/a bow lying across strings//not moving/held.”

PC: Have you ever attended a manuscript retreat (like Colrain) or hired an editor? If so, how was that experience?

TF: I have not, though I am lucky to have a few generous friends and colleagues who have read Seam and have given me thoughtful feedback. Ultimately, I want the process of writing, amassing, and reshaping a manuscript to be more my own than anyone else’s. Though I always take into consideration the opinions of others, I’m going to be stuck with myself as a writer for the rest of my life, so I might as well try to learn to trust my own impulses.

PC: Do you have a writing group?

TF: Lately, I privilege individual conversations over collective narratives. The closest I have to a writing group is The Grind, which emphasizes the disciplined and daily practice of writing over the course of a month, though you can participate many months in a row, and some folks do. Those of us who do The Grind make up a kind of family, because we are with each other through the rough, early, and often tenuous drafts of poems. I am also fortunate enough to be a part of Kundiman, an Asian American poetry collective. It’s not technically a writing group, but the ways in which Kundiman supports me and other Asian American poets are myriad.

PC: Do you have a submission process?

TF: I try to send my best work to journals and contests I admire. I’m a total nerd, and therefore keep track of my submissions via a color-coded Excel spreadsheet, inspired by Oliver de la Paz, who generously showed us his impressive submissions organizing system during last year’s Kundiman retreat.

PC: I’m writing a piece for Superstition Review about how much harder rejections are for me now that I’ve given up sweets. Do you struggle with rejections? What keeps you going?

TF: Rejection has been part of the process from the beginning. I send out and I send out, and then I send out some more. Sometimes it’s the acceptances that come in thin envelopes or with vague e-mail subjects, and other times, it’s the rejections. It’s interesting how comfortable one can get with failure—I stopped taking rejections too personally a long time ago, because I want to focus on the work, and any time I spend feeling sorry for myself is time spent away from the work. These days, because I’m submitting to first book contests, I’m fascinated and horrified by how much dread and excitement I feel when an unknown number calls. I’m humbled by the fact that usually, it’s an old friend whose number hasn’t survived my clumsy destruction of another phone.

PC: What do you do when you’re not writing/submitting?

TF: I just moved to DC a few months ago, so if I’m not missing a Metro train, I’m trying not to get lost. Otherwise, I’m trying to be as good a cook as my mother, teaching creative writing, helping edit Asian American Literary Review and Trans-Portal, and subjecting loved ones to repeated listens of my favorite song of the moment.

PC: Do you have a favorite, lesser-known, no-longer-living, female poet.

TF: Lynda Hull. Her intricate, beautiful, devastating poems make me want to weep, make me want to throw up my hands and never try to write again, and then somehow I find myself picking up the pen.

En Route to Bangladesh, Another Crisis of Faith

We pass over heavy shadows

of large clouds pinned to traincars

lined up like unused blocks

of colored chalk—red then green,

blue then orange—until we are

propelled higher, and the trains

are swallowed by these jagged

strictures of land that are no longer

sand nor rock nor water, but a child’s

drawing instead—until the distant ocean

is the only fabric that fills this punched-

out plastic hole of a window—that is

the blue that falls over everything, that is

everything—blue on blue on blue—like the one

strip of light left always on the airplane ceiling

that the pale, plastic shades cannot shut away—

until that narrow vein of light is the only

belief left, a cream-thick ribbon across our eyes—

(The Massachusetts Review)

———

Tarfia Faizullah’s poems have appeared in Ploughshares, The Missouri Review, Passages North, Poetry Daily, Crab Orchard Review, Ninth Letter, Southern Review, The Massachusetts Review, Mid-American Review, New Ohio Review, and elsewhere. A Kundiman fellow, she received her MFA in creative writing at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she served as the associate editor of Blackbird. She is the recipient of an AWP Intro Journals Award, a Ploughshares Cohen Award, a Fulbright Fellowship, scholarships from Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop, as well as other honors. Her manuscript, Seam, was recently named finalist for the Alice James Beatrice Hawley Award and the Crab Orchard Series in Poetry.