Henry James on Honoré Daumier

In juxtaposition to his stature as a theorist and practitioner of the art of fiction, Henry James’ writings on the visual arts are primarily known as the works of an art amateur. These publications mostly include exhibition notes that he sent back to American journals and newspapers such as Harper’s, the New York Tribune, and Century; James’ later and most sustained critical appreciations of John Singer Sargent and Honoré Daumier would appear after the majority of his art criticism had been already accomplished. The transformative “Art of Fiction,” published in Longman’s Magazine in 1884, came in the interval between.

The significance of this sequence lies in that masterful essay on his craft: James was able to articulate and synthesize with clarity the integral relationship he had come to perceive between the activities of writing and the visual arts. James remarks toward the beginning of “The Art of Fiction” that “the analogy between the art of the painter and the art of the novelist is, so far as I am able to see, complete. Their inspiration is the same, their process (allowing for the different quality of the vehicle), is the same, their success is the same.” The nature of the relationship, he goes on fittingly to observe, is both filial and competitive: the author “competes with his brother the painter in his attempt to render the look of things, the look that conveys their meaning, to catch the colour, the relief, the expression, the surface, the substance of the human spectacle.” Perhaps the competitiveness comes out most clearly in James’ 1890 essay on Sargent, a painter with whom James shared models similar in class and attitude. Indeed, James’ compliments of the younger man are often tempered by references to a certain stylistic facility that results in oversimplification.

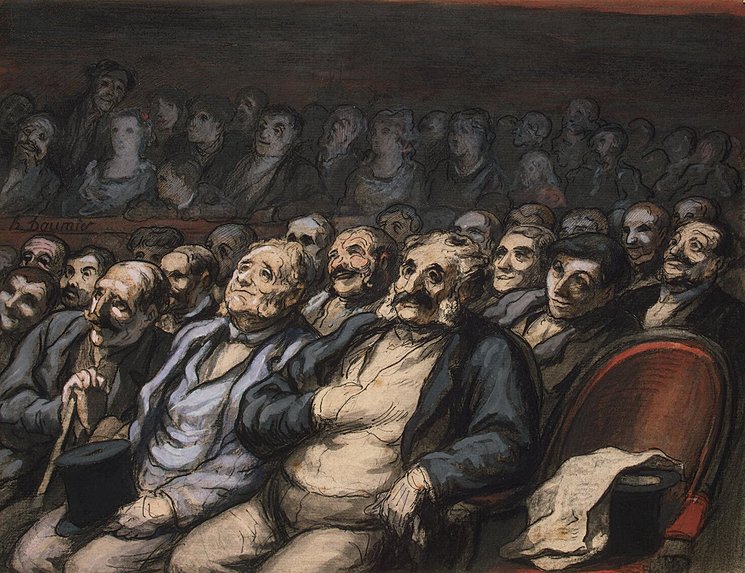

James’ meditation on Daumier appeared in Century Magazine in the same year, when James was turning his attentions away from the exhibition and toward the theater. Through its grappling with the juxtapositions between meaning and color, surface and substance, this essay further fills out yet another dimension to this relationship between the two art forms. James reports that he composed the essay in response to having just missed the exhibition de la Caricature Moderne at the École des Beaux-Arts. James’ description of his spontaneous encounter with the caricaturist’s work bears more than a passing resemblance to Daumier’s painting fittingly titled L’Amateur d’estampes:

at the hour I speak of, the old Parisian quay, the belittered print-shop, the pleasant afternoon, the glimpse of the great Louvre on the other side of the Seine, in the interstices of the sallow estampes suspended in window and doorway—all these elements of a rich actuality availed only to mitigate, without transmuting, that general vision of a high, cruel pillory which pieced itself together as I drew specimen after specimen from musty portfolios. I had been passing the shop when I noticed in a small vitrine, let into the embrasure of the doorway, half a dozen soiled, striking lithographs, which it took no more than a first glance to recognize as the work of Daumier.

This contrast between the serene Parisian afternoon and the “cruel pillory” fits perfectly his admission that it was dubious to pursue, outside the reification of a reputable exhibition, the “strange indigestible stuff of contemplation” that the French artist presented him. James’s reserved appreciation stands in contrast to many nineteenth-century artists and writers who admired Daumier’s work, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Eugène Delacroix, Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, and others. Even Honoré de Balzac, perhaps James’ greatest literary light, was an admirer. Had James been more aware of Daumier’s paintings, which he just mentions as an aside in the essay, perhaps he would have been more sympathetic to the French artist’s range of powers. But how else, then, to account for this divergence in view between James and the other artists who saw a talent in Daumier that exceeded mere journalism, political commentary, or aesthetic curiosity? It has something to do, of course, with issues of class, as well as with James’ often vague stance upon the relative aesthetic merits of beauty and ugliness in the visual arts, and, finally, with the perception that seemed, by this time, to extend to James’ attitude toward the visual arts in a more general way—that visual works variously risk oversimplification of the subject.

Part of the oversimplification, in the case of Daumier, has to do with the artist’s devoting himself to “the expression of the spirit for which humanity is definable primarily by its weaknesses. For Daumier these weaknesses are altogether ugly and grotesque.” Because this approach to representation violates all that James has loosely associated with the best in art, he finds something else in it that he can begin to appreciate with palpable ambivalence: Daumier’s “manly touch” that is “so full of the technical gras, the ‘fat’ which French critics commend and which we have no word to express. It puts power above all …. His persons represent only one thing, but they insist tremendously on that, and their expression of it abides with us, unaccompanied with timid detail.”

Even though he spends the majority of his essay condemning Daumier for his perceived limitations, toward its conclusion James generalizes that such characters “give us a strong sense of the nature of man. [His figures] are so serious that they are almost tragic.” James, for the moment, overcomes the problem of oversimplification when he comes to a sense of Daumier’s “strange seriousness.” Within all the violence, grotesquery, and bold approximations appears an unexpected collision between grandeur and misery. Perhaps the most vivid instance of this appears in Daumier’s La Parade (ca. 1865-66). James calls it “a page of tragedy, the finest of a cruel series.” He goes on:

It exhibits a pair of lean, hungry mountebanks, a clown and a harlequin beating the drum and trying a comic attitude to attract the crowd, at a fair, to a poor booth in front of which a painted canvas, offering to view a simpering fat woman, is suspended. But the crowd doesn’t come, and the battered tumblers, with their furrowed cheeks, go through their pranks in the void. The whole thing is symbolic and full of grimness, imagination, and pity.

Later critics would identify this work as Daumier’s embodiment of the artist-hero in relation to the culture in which he finds himself a part but unavoidably separate from at the same time. Of the many ideas James approaches in the essay, Daumier’s “strange seriousness” is the one that has had the most lasting resonance. For yet another artist whose career and life ended with nowhere near the degree of recognition that the posthumous period has brought, the ongoing yearly international exhibitions featuring Daumier’s work attest to the staying power of his vision. For James himself, this embodies the filial connection between the artist and the novelist—with all of the love and strife that implies.