“I Refuse to Review”: Literary Criticism and Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death

The first time I sat down to read Don Mee Choi’s translation of Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death, a collection of fifty poems that—except for the last—each represent a day in which the spirit roams the world after leaving the body at death, I could hear my grandmother getting ready for bed in the next room. Earlier that day I had discovered a poem, untitled and scrawled on a weathered piece of paper, among her things. It read:

I stayed too long

watching the bats fly

in the warm summer evenings.

I should have flown away,

blown away,

hurried through the exit sign.

Instead, I stayed

drinking Canadian Club

blurring the edges

of the escape route in my soul.

And when I looked

there were no wings left

in the locker room.

She had been pickling onions one hot August day in 1979—looking out over the fields in the furthest easterly tip of England—expecting my grandfather to arrive back soon from his workshop, where he fixed up machinery to sell. She was married at nineteen with little family—her mother had died of a miscarriage when she was a child, her father remarrying soon after and sending her to live with an aunt—so she stood by the window pickling onions on a day in which her life did not feel her own, when a feeling came over her, pure sensation. It culminated in a single thought: “I just knew I wouldn’t be there the same time next year.” It was a decision as much as a desire: to leave an unhappy relationship, an unhappy life. It wasn’t a weighing up of pros and cons—leaving was potentially impossible as she had little money of her own saved from her hairdressing job—but rather an instinctual bodily feeling, a “just knowing.” “Poetry comes to know that things are,” writes Lyn Hejinian in The Language of Inquiry, “but this is not knowledge in the strictest sense; it is, rather, acknowledgement—and that constitutes a sort of unknowing.”

That same year, Kim Hyesoon debuted her poems and became one of the first women in South Korea to be published in a literary journal, while General Chun Doo-hwan—already trained in “psychological warfare” from his time at a “special combat school” in the US—led a coup in her country that resulted in a US-backed military dictatorship, one that oversaw the mass killing of citizens. In Autobiography of Death’s translator’s note, Choi recalls how Kim was working as an editor at the time, and had to frequently visit city hall to submit each manuscript to the military censors for review. Kim spoke of one play that was returned to her completely redacted, except for the title and author’s name. She remembered weeping through the play’s debut as the actors performed it entirely without speaking.

To speak back—to speak “up” and “out”—is often considered the strongest form of resistance to repression and censorship. But how to speak of—speak back to—that which is created “inside the world of parting” as Kim says of Autobiography of Death—that which exists in the gaps—the gutter—between language, between violence, between death? “It feels very normal for poems to be ‘inspected,’ ‘looked at,’ ‘examined’ ‘investigated,’ ‘explored,’ and even ‘interrogated,’’ write Jo Walton and Ed Luker in Poetry and Secrecy. “Even more than this, the whole practice of literary criticism tends to organise itself around the inspectability of its objects, and the necessary alignment of scrutiny and knowledge.” Whether intentional or not, much of current review culture presents reviewers not as readers, but as elevators of reading—subscribing to the idea of objective, universal interpretation and a prescriptive approach to reading. We are afforded our own subjectivities in writing, but not, it seems, in how we approach the writing of others in public, in print.

Johannes Göransson, who as editor of Action Books along with Joyelle McSweeney has published much of Kim’s work in the English-language market, draws attention to how “the idea of context as a stable, determining force has become pervasive in our culture…that context [then] basically determines ‘meaning.’” Göransson instead argues that “what translation—and art!—does is continually forge new contexts.” Similarly to how there cannot result one “true meaning” of a poet’s work based on the supposed “stability” of the context in which they’re writing and living, there is neither “one true context” for reading, interpreting—and thinking on (as an alternative to “theorizing”). In allowing ourselves and our surroundings to filter through the cracks, context no longer becomes the attempt—as in many reviews—to master, “quarantine” or “instrumentalize” (as Göransson writes of translation) a book, but to enable ourselves to be “overcome, possessed and changed” by the context in which we live—here, now, alive. “We are committed to giving each other the space for such an opening, and we call this gift politics,” write Lisa Robertson and Matthew Stadler in their introduction to Revolution: A Reader. Through her essays and the brilliant pamphlet Freely Frayed,ᄏ=q, & Race=Nation addressing the ever-present political aspect of translation, Choi offers this opening, writing about the feminist and decolonizing strategies of her translation process—why “translation must continue to remind us of the hell within and outside of the US empire.”

For Kim, poetry is a place in which “names are never called out. It’s a place where names are erased…To write poetry is to witness the names that die inside poetry.” Rather than attempting to bridge (and therefore, like “bridge” translations, disappear) the gaps within language and living—between life and death, self and other, absence and presence, memory and future—that Kim’s work has always alerted us to, Autobiography of Death recognizes the possibilities of preserving the gap—of inhabiting the gap, the gutter. “Perhaps poetry can be a space where it is not only the capacity to seek knowledge that is awoken and compensated in complex ways, but also the capacity to draw back from knowledge, to honour the keeping of secrets,” Walton and Luker propose. Can secrecy, most often alluded to in reviews through the label of “difficult,” protect from and resist erasure? Does secrecy deny the act of “speaking out,” or is it a different form of speaking out? “A poem is not going to give precise directions,” the British poet Anna Mendelssohn wrote, “you mustn’t touch the hiding places.” While Autobiography of Death draws on many “tragic and unjust historical events” that have taken place in South Korea—such as the Sewol Ferry Disaster of 2014, in which over 300 (mostly school students) died—Kim refuses to name specifics, stating in an interview with Choi, “Only I know that the poems are based on those fatal events.”

Yet Autobiography of Death recognizes the necessity of persisting nonetheless, of tracing lives erased and extinguished by political repression, patriarchy, and capitalist imperialism—like the neoliberal practices of deregulation and privatization that led to safety violations onboard the Sewol ferry. “But many secrets should never have been hidden at all,” say Walton and Luker. “I Want to Go to the Island: Day Twenty” asks, “What if starting tomorrow the days without sunrise continue? / Then we’d be inside this black mirror 24 hours a day, and who’d dip a pen into the mirrorwater to write about us? / Why is there so much ink for writing?” Elsewhere Kim refers to how “we have shamefully stayed alive” to witness what fellow poet Yi Yon-ju discerns as, “those who are dead because of those alive, / their bodies incinerated each night”—and the collusion between state governments to package and present them publicly as anything other than what they are. The speakers in Autobiography of Death live in the gaps between these disputed states of being and believing—scrawling their shrieks across toilet stalls, abandoned classroom desks and among the rubble of collapsed department stores—all of the places filled with the presence of absence:

Stepmom has died. Just now

The clear silence of the shimmering crazy bitch

lifts up the house

Throws down the house

The underground stream gushes out

“Hiccups: Day Thirty-One” exists firmly within the “structure of death” that presides over the book—a structure that we remain living in. Autobiography of Death makes me think of Véronique Le Guen, a woman who spent 111 days living alone in a cave 275 feet underground in France as part of a scientific experiment in 1988; she set a world record for the longest time spent in isolation. Deprived of natural light or a clock, her only contact with the outside world was through the telephone calls she received from the experiment’s team. “The calls put into my ears the sounds of people living without me, in the free air,” she said, before dying by suicide two years after the experiment. Kim says that what the poems in the book are reaching for is “sound”; I think of them as reaching for the sounds of all the people subsumed by the structure of death—both above and below ground. The air, however, is far from Le Guen’s “free”—cue political repression, cue patriarchy, cue neocolonialism, cue capitalism and the social conditions it creates—cue “Commute: Day One”:

You must have bounced out of the train. It seems that you’re dying.

[…]

Oh what’s wrong with this woman? People. Passing by.

You’re a piece of discarded trash. Garbage to be ignored.

[…]

Will I get to work on time? You head toward the life you won’t be living.

Kim has said that since the Sewol ferry capsized, “words such as ‘child’ or ‘sea’ are yet to function as metaphors for me…When you live in a society where these experiences keep repeating themselves…people’s freedom is lost and metaphor loses its brilliance.” In being “of” death, Autobiography of Death denies the distillation of poems—of lives—into “aboutness.” This is sharpened through the shift from “I” into the relentless “you” that proliferates and reverberates throughout the book—reminding us that language “not only exists in multitudes of context, it is multitudes of context,” as Lyn Hejinian writes. By being “of” and not “about” death, Autobiography of Death recognizes both individual and collective involvement in the structure of death—unable to unstick itself from the structure of power. Secrecy, too, is power—as is resistance; to “speak out” is not to speak outside of power—“power has no outside” as Kim has written. In observing this, Autobiography of Death shakes off the poetically omnipresent and sloganized function of poetry as necessarily “transformative” or “transcendent.” Rather, as Choi has previously described, “there is no before or after hell. All is hell.”

Like Le Guen reminded of her own conditions in the cave through the sounds of a world occurring outside, Autobiography of Death explores how death is dependent on its proximity to living bodies, those which register the spaces—the gaps—that will be left when we leave this place. Neo-colonialism and global capitalism attempt to subvert this, rendering some bodies more forgettable than others—but no one is marginal to their own life. The speakers in Autobiography of Death remain dead yet alive, erased and yet continuing to exist. This is not transcendence, as each is kept alive by death. To transform is not to abolish, we are warned. The final lines of the final day—“Don’t: Day Forty-Nine”—wonder: “Don’t miss you just because you’re not you and I’m the one who’s really you / Don’t miss you as you write and write for forty-nine days with an inkless pen.” This might be what it means to speak in the silence of erasure, to protest through the dying language and yet have them remain secret, “inkless” and invisible.

The collection ends with “Face of Rhythm,” a sixteen-page “follow-up” poem about individual pain, illness, and meditation; the “I” reappears here, but offers a “rhythm” that “isn’t a method of existence but a method of lack.” Reading “Face of Rhythm,” I’m reminded of a line from the poet Alejandra Pizarnik: “How I would have loved to see myself in some other night, beyond this madness of being two sides of the mirror.” Mirrors—“black mirror,” “mirrorwater,” “mercury mirror”—pile up in multitudes throughout the final poem and the forty-nine days preceding it. Although “Face of Rhythm” situates us on the other side of the mirror, its speakers have not transcended one side to reach the other. Rather, like the artist and author Unica Zürn who divided herself “into two halves” as a strategy for survival, a “twoness is forged,” one that echoes defiantly: “I’ve split in two but I’m alive.”

“A common vocabulary is not necessary, and probably not desirable,” Lisa Robertson and Matthew Stadler write in Revolution: A Reader. I often think of something the poet C. D. Wright wrote: “There are so many approaches, so many innovative moves, so many oddly shaped ears in the field; may they never sing in unison.” In one of Choi’s own books, Hardly War, she repeats lines of Korean text, then, beneath the Hangul, writes in English, “I refuse to translate.” Translation is so often used as a tool of “integration”—of state-sponsored assimilation and standardization—to suppress the proliferation of ways of being, seeing, and feeling in favor of a dominant “universality” which only ever represents a select few. Poetry translations too often simply substitute one “stable” context for another. Choi’s translation work demands us to question what might be possible, what we might be able to see more clearly, if language inhabits the gaps between contexts—the hiding places in which Autobiography of Death’s own speakers reside. By refusing to substitute our own experiences and contexts in reading and reviewing for “objective” understanding that privileges critique over sensation, we reject the idea that a poem would be—feel—the same reading it aged twenty as reading it thirty years later. Their “aboutness” would differ.

Nothing appears from nowhere. For reading and reviewing—for my grandmother to be able to have left the life she could no longer live—subjectivity must give way to agency. “If it’s not all juxtaposition, she asked, what is the binding agent?” wrote the poet Forrest Gander. By allowing ourselves to discover and create connections and associations—to be the “binding agent,” present to that which surrounds us, whether it be a grandmother, the books we’re reading at the same time, snippets of conversation on the bus, or anything going on while everything else is—we permit poems to be altered by our looking. We too can then live within the gaps. But first we must look.

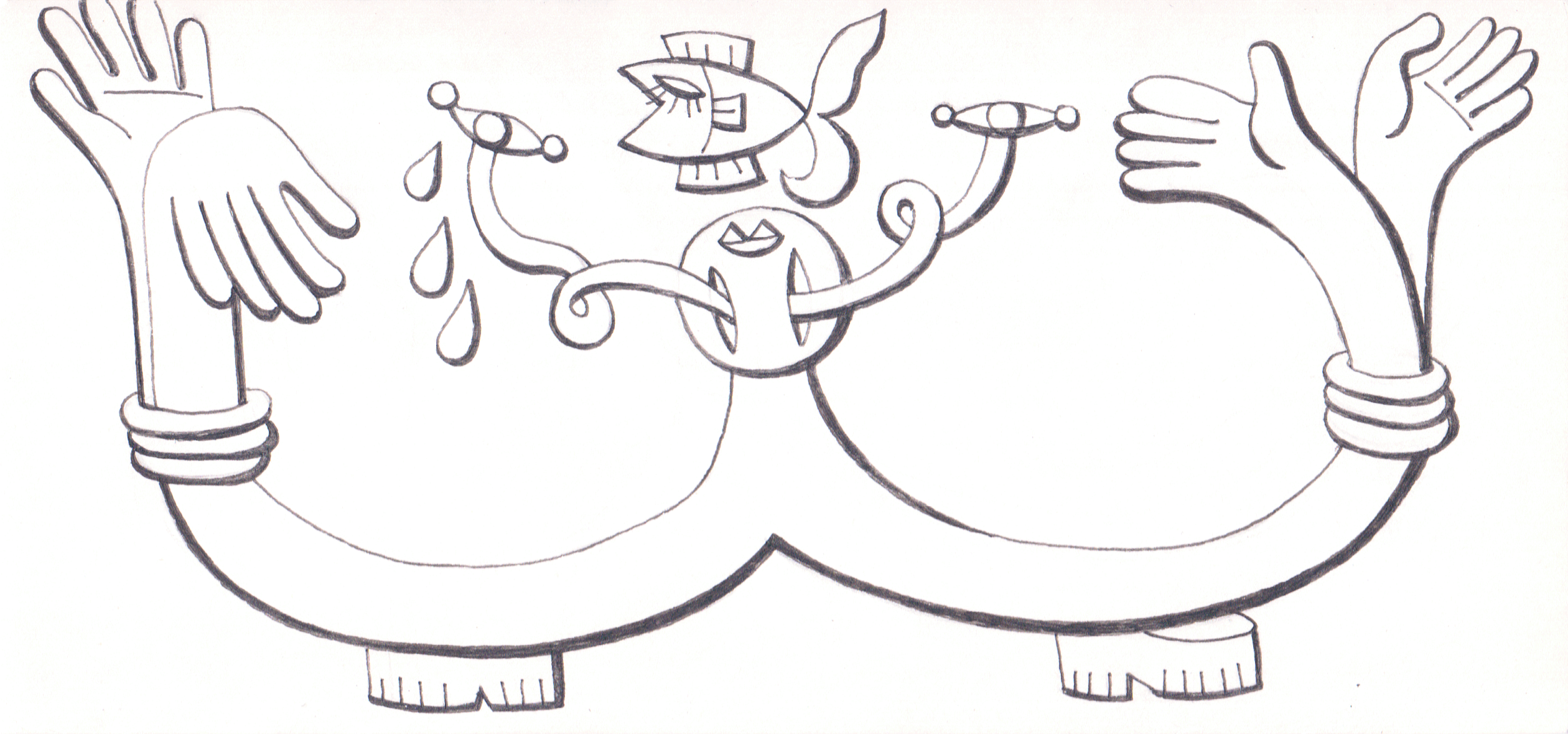

Artwork by Fi Jae Lee