Interactivity and the Game-ification of Books

As an undergrad studying creative writing one of the first things I remember learning was the sin of gimmickry. Readers, I was taught, would see through your cleverness—it would be vile to them and they would hate you. But as a kid and teenager my favorite books employed some pretty neat sins and I don’t remember ever hating those authors. I relished a novel approach to novels and welcomed those books that didn’t just swim in standard conventions. Some of the most memorable artifacts of my youth, in fact, were more bound riddles than books, and each riddle taught me how to open myself up to uncertainty, ambiguity, and irresolution (all concepts more true to life than your traditional cut and dry, happily-ever-after tale).

More specifically, the books I tended to gravitate toward were texts in which the role of the reader could more aptly be described as that of a player, or collaborator. (Though one could argue all books are collaborative in nature, the ones I tended to flock to were especially open-ended, demanding a higher degree of interactivity.) I would remain captivated by these books infused with a sense of play/collaboration and it would eventually become an important element in my own work.

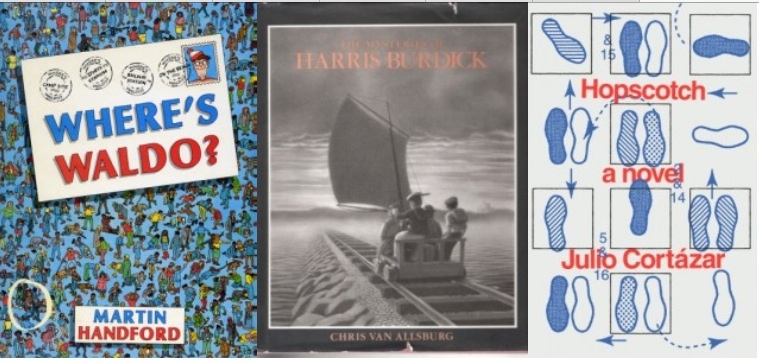

I first devoured picture books like the Where’s Waldo series, for instance, less interested in the eponymous red and white striped protagonist than in the sheer overstimulation of colorful characters and anachronistic situations swirling in the background. They might have been my first writing prompts, actually. I remember writing little stories about the wizard and how he came to be lost in the scene, or what events must’ve transpired to rip a Viking out of time and space to plop him smackdab in the center of a bustling mall.

Later I would discover Chris Van Allsburg’s The Mysteries of Harris Burdick, in which the strange and surreal black and white illustrations of Allsburg juxtaposed with terrific titles and brief captions, nothing more, challenge you to play detective and ferret out the story for yourself. (For example, the picture of a nun seated in a levitating chair, floating aloft through a cathedral is titled THE SEVEN CHAIRS, with the caption “The fifth one ended up in France.”)

And, of course, the Choose Your Own Adventure series was a revelation. That I could “lose” within only a few pages if I wasn’t careful taught me a crucial lesson about consequences, reminiscent of the wisdom of Heraclitus: The content of your character is your choice. Day by day, what you choose, what you think and what you do is who you become. I vaguely remember dying in one book because I had failed to notice some seemingly insignificant detail about a monster. I had failed to observe that the blood on its hands was its own, not that of a victim—that it had been wounded, and though it would have gladly accepted my help, guiding me safely through the dark forest to return the favor, it instead had been left with no choice but to become the monster I assumed it was when I rushed to preemptively attack it.

When I got older, I discovered that this sense of play wasn’t limited to the young. There were plenty of adults out there writing radically experimental books formally guided by the notion that a book could be more than a book—it could be a vexing puzzle, a winding labyrinth, a stubborn gauntlet, a spooky carnival full of creaky rides, even a sandbox. It could be anything it wanted to be, subject only to the vision and craft of its creator.

For Hopscotch, Julio Cortázar loosely borrowed the artifice of a child’s game, allowing the reader to choose their own progression through the story. With Speedboat, Renata Adler gave us a frenetic flipbook of dream-fragments while Mark Z. Danielewski crafted an ergodic tome of textual cat’s cradle with House of Leaves. The French novelist Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1—a box full of 150 loose, unbound pages—is basically the equivalent of a Legos set missing the instructions. Books such as these, which many writers and reader have attacked for their sinful gimmickry over the years—that lot of purists for whom the word experimental will forever remain a dirty word—represent the incredible elasticity of the novel. They are a testament to the book’s ability to slough off tradition and chameleon into whatever it wants to be, by adapting and absorbing other forms, even a game.

Today the tradition of game-y literature (or “play lit,” if you will) continues. The books of Keri Smith are interactive diaries which eschew narrative altogether, challenging young readers to explore the outdoors, “create as many sounds as they can using the book, like flipping the pages fast or slapping the cover,” and joyously deface or destroy large portions of pages in creative ways. Ben Carey’s This Book Will Change Your Life is basically a print version of truth or dare in which you’re given an excuse to do things like glue a spatula to your arm. S. by J.J. Abrams challenges readers to read between the lines, literally, to unlock the Rubik’s cube of a story behind a story in a meta-love letter to marginalia. Horrorstör by Grady Hendrix is “a traditional haunted house story in a thoroughly contemporary setting…packaged in the form of a glossy mail order catalog, complete with product illustrations, a home delivery order form, and a map of Orsk’s labyrinthine showroom.”

The jubilant experiments belonging to this genre offer a more active and whimsical experience, one bound to tickle a reader’s creative muscles and delight in the way a playground at recess once delighted us so: by inviting us to play, without shame and far from the restrictive, disapproving eyes of the teacher.