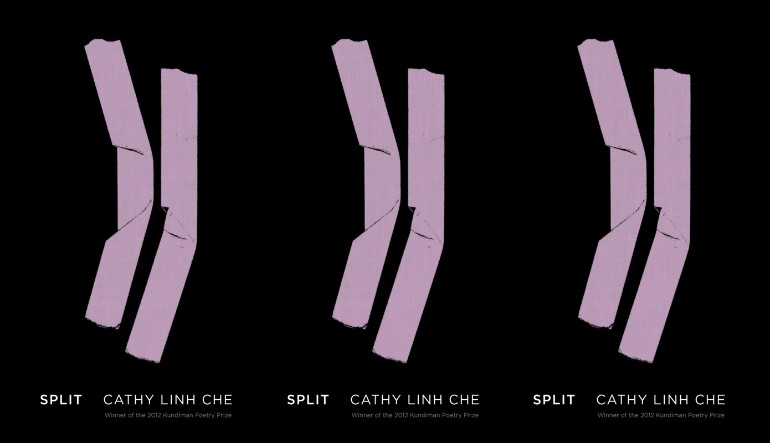

Interview With Poet Cathy Linh Che

Cathy Linh Che is the author of Split (Alice James, 2014), the winner of the 2012 Kundiman Poetry Prize. She received her MFA from New York University and is the recipient of fellowships from The Fine Arts Work Center at Provincetown, Hedgebrook, and Poets House. She currently teaches at NYU Poly and is Program Assistant for Readings/Workshops (East) at Poets & Writers.

Jennifer De Leon: What first brought you to poetry?

Cathy Linh Che: I would have to say that my parents brought me to poetry. Though neither one is a poet, my upbringing was filled with their stories. While sitting at the dinner table, my parents would tell me about their lives during the Vietnam War, the year in a refugee camp, their first years in the U.S. When I began writing, their voices demanded to be told. I couldn’t help but see their stories as fundamentally part of my own.

JDL: What inspires your writing?

CLC: Reading great poetry inspires my writing. I don’t think I’d be a poet if I hadn’t been taken in by its particular magic. I love poems that are deeply felt and teeter on the edge of ruin. I love tenderness. I love intelligence and mystery.

I also find silence very motivating. In my poems, I try to write out the silence that surrounds war and sexual violence. Of course, war and rape are loud topics, but those who are most affected by them don’t often speak out and when they do, they aren’t often heard.

At this year’s Split This Rock Poetry Festival, Patricia Smith talked about ‘the pressure of stories.’ Stories help to change the conversation. My parents’ stories and my stories aren’t part of the dominant American narrative, and why I write, I suppose—to write us in.

JDL: A theme I have tried to touch upon during this blog series is that of ‘bridging the divide.’ I am deeply interested in the ways in which first and second-generation writers straddle the demands and dreams from various worlds. Can you tell me about your own experience as a Vietnamese-American writer? How do you navigate cultural expectations?

CLC: I’m still tussling with the gap—all that is implied in the hyphen or the space between Vietnamese and American, and I don’t know if I’ll ever understand or resolve it.

I was raised in Highland Park in a working class Asian and Latino immigrant community. So, while there were plenty of clashes between my parents and me, it was something that everyone around me experienced—so I never felt different or alone until going away to college.

College was something else. I was miserable as an undergraduate. The students were mostly white and affluent and they just didn’t see me. In class, a student once said, “We’re all white here”—even as I sat across the table from her! Every day, people would stare at me as I walked across campus. And yet, when people would speak to me and a white friend, they’d only address her, as if I weren’t there (or perhaps, they were expecting her to translate for me).

It was during this period of alienation that I wrote out my parents’ stories. Maybe it was a way to bring my family closer to me, or maybe it was a way to explain myself to the people who just didn’t understand me. I don’t know.

Until a few months ago, neither one of my parents had read my poems. On some level, it’s because I write in English, and my parents and I communicate in Vietnamese. But I also like to keep my life compartmentalized. Here, in New York, is my writing life. There, in Long Beach, my family and friends. Here, I’m Cathy. There, I’m Linh. I’m still working on it!

JDL: You recently won the 2012 Kundiman Poetry Prize which includes publication of your poetry collection by Alice James Books in 2014. Congratulations! Where were you when you discovered the news? How did you let your family know?

CLC: A member of the Alice James board called and told me I’d won! I couldn’t believe it! I remember my first sentence was something like: “YAY! Oh, but it’s not ready yet!” He reassured me that I’d have time to revise, and then I started pumping my arms like a train and running circles around the kitchen table making crazy Three Stoogies whooping noises. I’d stop for a minute, then get up and do it again!

I flew back home to California for a brief visit the following week. I sheepishly told my little brother, then my mom, then my older brother. It was kind of like in the movies where you write down a figure then slide it across the table. I was really shy about it.

JDL: So much of what I love about your work has to do with its incredible, poignant balance of time. In a single moment between mother and daughter, you give us history, herstory.

In “Bloodlines,” you write:

With a quarter,

I scrape, press down,bruise the skin,

pink, then red,then purple. Good, she says.

That’s poison drawn out.When I dig in,

the bloodlines emerge,rib from spine,

each line a bone,each bone

a story.I excavate

the war, a seizure,my older sister

buried somewherein the motherland

Can you share the genesis of this particular poem?

CLC: There’s a cure for the common cold or flu called cao gió, which literally means “scrape wind.” The idea is that you got sick because you’ve been exposed to a poison wind, and the way to become unsick is to release this poison by scraping a coin over and over in a single line across the back until redness appears. Then you repeat the process until creating what looks like a skeleton. (Look up images of cao gio, and you’ll see what I mean.)

Growing up, my mom performed cao gió on me when I was sick, and as I’ve gotten older, I did the same for her. We would talk during cao gió. I’d ask questions, and she’d tell stories.

I always felt that I was literally drawing these stories out of her. In the poem, I wanted to enact this process, where the appearance of these red lines coincides with the revelation of buried secrets.

JDL: What’s next?

CLC: Well, I’m still revising my manuscript—writing new poems and changing old ones. I’m also currently super-employed—a full time job and two part time jobs, which is a new development, so I’m figuring out how to balance out different areas of my life.