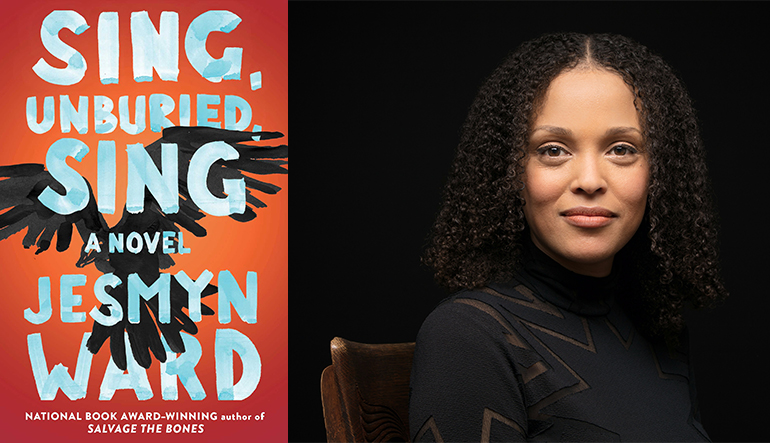

Jesmyn Ward’s Southern Roots

Jesmyn Ward has proven to be, in her decade-long and award-garnering career, a versatile writer. She’s published short stories, three novels, a memoir, and edited a collection of essays on race titled The Fire This Time. But while her style and format has changed, all of her works are centered on the American South, primarily in the area of Mississippi between New Orleans and Biloxi. The Mississippi of Ward’s books is a land of devastating natural power, of backwoods drives where the seats for social gatherings are the hoods of cars, where any traffic is expected or suspect, and where every iota of pleasure life offers her Black characters is overcast by clouds of tragedy and fear.

Jesmyn Ward has proven to be, in her decade-long and award-garnering career, a versatile writer. She’s published short stories, three novels, a memoir, and edited a collection of essays on race titled The Fire This Time. But while her style and format has changed, all of her works are centered on the American South, primarily in the area of Mississippi between New Orleans and Biloxi. The Mississippi of Ward’s books is a land of devastating natural power, of backwoods drives where the seats for social gatherings are the hoods of cars, where any traffic is expected or suspect, and where every iota of pleasure life offers her Black characters is overcast by clouds of tragedy and fear.

She grew up there, in a small town called DeLisle (population 1,147 in the 2010 census), and her prose has returned to the region again and again, and with each revisitation she digs deeper, reexamining the same themes with a new and brighter light. Her latest novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, which was longlisted for the 2017 National Book Awards last week, carries on this vein. It’s centered on three generations of a Black family: Leonie, her half-white children Jojo and Kayla, and her parents Pop and Mam. Each generation has been shaped and continues to be shaped by their own trauma, traumas that are personalized but depressingly close to being interchangeable.

The narrative of the book is centered on a road trip to pick up Jojo’s white father, Michael, from the Mississippi State Penitentiary, or, as it’s better known to the characters of the book, Parchman. Decades before Michael was locked up, Pop had served time there as well, doing back-breaking slavery-by-another-name labor in the work-farm fields.

Pop came out of Parchman with the blood of a fellow inmate on his hands; Michael exits with a desire to garden. This reflects the difference in racial experience with governmental institution, but that’s not to say that Michael is unscathed while moving through the world. He tries to overcome his own racist family and is haunted by his own flavor of PTSD at the hands of being a worker on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig.

Like the regional setting itself, the past is never further than arm’s reach from the events of the novel. History overlaps with, influences, and outright intrudes on the present, and in Ward’s fictional world that happens metaphorically, mentally, and then literally through visions and ghosts. Jojo is drawn to the power of the stories of the past, begging his grandfather to endlessly repeat the same handful of tales:

Hearing him tell them makes me feel like his voice is a hand he’s reached out to me, like he’s rubbing my back and I can duck whatever makes me feel like I’ll never be able to stand as tall as Pop, never be as sure. It makes me sweat and stick to the chair in the kitchen, which has gotten so hot from the boiling goat on the stove that the windows have fogged up, and the whole world is shrunk to this room with me and Pop.

These stories are at the heart of the book. How does Pop try to prepare Jojo for facing the world, given Leonie’s inadequacies as a mother? What does Pop’s wife Mam do with her last days on Earth as she’s dying of cancer? When drug-addicted Leonie has lucid moments, what does she do to try to redeem herself? The answers to these questions are intertwined with the history of both the family and their country’s relationship with race. A police stop during their road trip immediately echoes back to Pop’s own reason for being in Parchman. The friends and family who have been lost are always in the characters’ thoughts, as is the possibility of losing the people around them who remain. Ghosts watch over the character’s shoulders as they move through the world.

Mam sums it up succinctly when she says, “We don’t walk no straight lines. It’s all happening at once. All of it. We all here at once. My mama and daddy and they mamas and daddies.”

Ward built her story on this overlapping of past and present, on the layering of trauma over trauma. The epigraph of Sing, Unburied, Sing contains a Kwa chant, a snippet from Eudora Welty, and an excerpt from Derek Walcott. The South of the novel is all of these things: centuries of history from a swirl of races and distant corners of the world. Many stories would depict the weight of this history but ultimately end by expounding upon the strength such a foundation can offer. Ward does not offer a cheery out, though. Mam and Pop and everyone that came before them offer Leonie and Jojo strength, but the characters and Ward’s narration are all almost certain it won’t be enough to combat the unending oppression working against them. It’s brutal, it’s depressing, and it’s tough to argue with.