Navigating the “Pitiable Skull” in Jean Stafford’s The Interior Castle

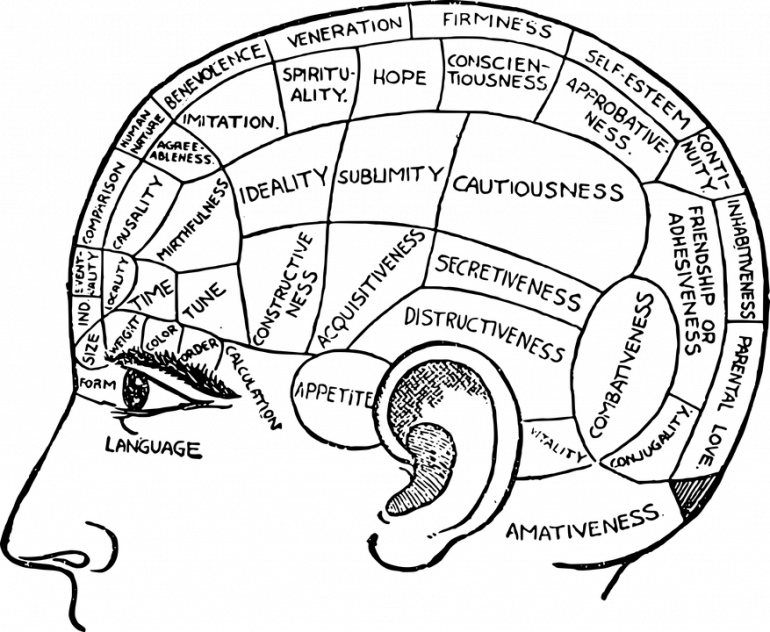

How characters locate themselves in a story shows readers how they encounter the world around them. It provides roots—gives them an identity. In the case of Jean Stafford‘s The Interior Castle, the setting is a hospital room and a surgical ward. It’s also the imagined space inside the protagonist’s skull. Told from the perspective of a woman who’s barely survived a horrific car accident, readers enter Pansy Vanneman’s mangled head, roaming imagined corridors of the mind, protecting her “brain”—a treasured artifact she keeps hidden from the hospital staff, those she believes would take away access to her mind. Stafford utilizes imaginary settings to display the importance of self-ownership and authority. By placing significance on the concrete and the ephemeral, writing about instances of control, and using pain as a ballast for maintaining boundaries between the real and the imagined, Stafford actualizes setting as a marker for autonomy. When place is lost, self is lost.

How characters locate themselves in a story shows readers how they encounter the world around them. It provides roots—gives them an identity. In the case of Jean Stafford‘s The Interior Castle, the setting is a hospital room and a surgical ward. It’s also the imagined space inside the protagonist’s skull. Told from the perspective of a woman who’s barely survived a horrific car accident, readers enter Pansy Vanneman’s mangled head, roaming imagined corridors of the mind, protecting her “brain”—a treasured artifact she keeps hidden from the hospital staff, those she believes would take away access to her mind. Stafford utilizes imaginary settings to display the importance of self-ownership and authority. By placing significance on the concrete and the ephemeral, writing about instances of control, and using pain as a ballast for maintaining boundaries between the real and the imagined, Stafford actualizes setting as a marker for autonomy. When place is lost, self is lost.

Who Pansy was before the accident is a mystery. She has no identity outside of her head, her injury, and the hospital room, which is a bland, bleary limbo. Time passes indiscriminately. There are no seasons. No cityscape or town. Sterile descriptions of space reinforce the monotony:

Her room accomplished no alterations from day to day. On the glass-topped bureau stood two potted plants telegraphed by faraway well-wishers. They did not fade, and if a leaf turned brown and fell, it was soon replaced; so did the blossoms renew themselves.

There’s little to anchor readers to the present outside of what’s happening with Pansy’s surgery and how she endures pain. At one point, Pansy spots a ribbon on one of the flowerpots and understands that Christmas passed without her notice. The outside world is a window in her hospital room, highlighting weather that is singularly dreary, cold, and gray. But unlike the bleak uniformity of her hospital room, Pansy’s brain is described in glowing, exclamatory detail:

The physical organ which she envisaged, romantically, now as a jewel, now as a flower, now as a light in a glass, now as an envelope of rosy vellum containing other envelopes, one within another, diminishing infinitely. It was always pink and always fragile, always deeply interior and invaluable.

The flavorless exterior of Pansy’s world—populated by a faceless, nameless hospital staff—and the richness of her interior life show what’s important to the story. By drawing parallels between the gray, nonexistence of the hospital room and the luminous, detailed brilliance of the mind, Stafford allows readers a richer insight into the significance of Pansy’s self-ownership. Her brain and where it’s housed is worthwhile because it is hers to map—hers to own and control. The room might be barren and her body might be broken, but her mind is fecund, flourishing. It’s the landscape that matters.

Alongside the concrete and the ephemeral, control determines autonomy and setting in The Interior Castle. One way Stafford does this is by showing readers how Pansy experiences and attempts to control pain. It is a consuming, violent force. Aside from her interior life, pain is the only thing described in rich detail. Unlike the beauty of her brain, however, pain is a monster that causes misery and fear.

The demon, pain, which skulked in a thousand guises in her head, and which often she recklessly willed to attack her and then drove back in terror…to be sure, it came of it’s own accord, running like a wild fire through all the convolutions to fill with flame and leave the small sockets and ravines and then, at last, to withdraw, leaving behind a throbbing and an echo.

Pain is a constant presence. Like the weather and the hospital room, it cannot be controlled, but rather endured. While Pansy works to keep her interior life sacrosanct, outside forces work to drive into her head. One of those invaders is Pansy’s surgeon, Dr. Nicholas. Pansy denies him access to her pain, hiding reactions to his invasion beneath a veneer of calm detachment. Controlling her reaction to pain is one way that Pansy keeps her autonomy; this allows her to maintain the closed borders of her mind:

There was, for example, the matter of her complete passivity during a lumbar puncture…except for a tremor in her throat and a deepening of pallor, there were no signs at all that she was aware of what was happening to her.

Dr. Nicholas repeatedly scrapes and prods at her with his surgeon’s tools, implements he uses to reshape her face. Pansy fears pain in these encounters, but mostly, she is afraid of allowing access to her “sacred brain,” the landscape she values above all else. While he works to ready her for surgery, she uses the pain as a way to focus on closing access to her innermost self. Her nose is prepped and stretched with gauze and anesthetic. The landscape of her face—her concrete physical identity—is of no consequence to Pansy. When the nurses hold her up to a mirror to see how funny she looks with wads of cotton stuffed inside her nostrils, Pansy stares at a stranger. Her true self, her autonomy, is entirely inside her head.

After the anesthesia is administered and she receives a narcotic, Pansy loses control. Since pain is no longer an issue, she’s unable to use it as a locus, cannot grasp what’s occurring as the surgeon works to right the mess of her nasal cavity. Pansy floats unmoored above the scene in the operating room, separate from her body. It’s only when the doctor makes a statement about her brain that she startles to action:

A murmur, sanguine and slumberous, came to her and only when she had repeated the words twice did they engrave their meaning upon her. Dr. Nicholas said, “Stand back now, nurse. I’m at this girl’s brain and I don’t want my elbow jogged.” Instantly Pansy was alive. Her strapped ankles arched angrily; her wrists strained against their bracelets. She jerked her head and felt the pain flare; she had made the knife slip.

By conceding momentary access to her brain, control is taken from Pansy. Once she’s back in her hospital room, she looks around and notes that things remain unchanged—the gray, dreary weather outside her window, the same plants, sheets, and water pitcher. But her treasure, the “sacred brain” she had so valued, is gone. The landscape is altered and inaccessible.

Throughout The Interior Castle, Pansy’s autonomy is viewed as something valuable and worth protecting. It’s also utilized in conjunction with place and identity. Because Pansy’s lost in the unreality of the situation—the accident, its aftermath—we are shuttled alongside her into her mind, a space where she maintains authority, more vibrant than the airless, lifeless void of the hospital room. When that space is violated, Pansy loses what little control she had over her life. We feel the loss as keenly as she does.