Pop Survey: Do You Write in Your Books?

It’s a digital age, but we’re still mad for paper! Even as readers embrace the connectivity and convenience offered by iPads and Kindles, there are still many good reasons to celebrate a book’s physicality. In Ploughshares’ Book Arts series, we’ll be looking at some of the artists, curators, and craftspeople who work to keep things fresh and relevant.

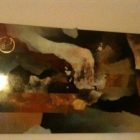

Marginal notes re-purposed to create fine art: “A black rose is planted over the scrawled notes of some long ago student struggling with the text of Macbeth….The student’s handwriting is so uncertain and you feel the tremendous desire to understand. I like the anxiety and striving to grasp the meaning of the printed word.” Jane Buyers, Notes on Macbeth: Enter Lady Macbeth, 2004. Lithograph, etching, chine colle. 81.5 x 102 cm. Photo credit: Laura Arsie. (Via Numéro Cinq, used with permission. Visit NC’s site for the full interview.)

Okay, Ploughsharers, it’s time to share some of your opinions! Today we’re taking a little squiggly, ink-stained side road in our journey through book arts with a special question just for you:

Do you write in your books?

Or do you prefer to keep them pristine?

(Tell us in the comments section below!)

Readers are a passionate bunch. I did a little informal pre-survey of some of my friends and found the responses ranged from horrified gasps of “No, never!” to enthusiastic, fist-pounding “Hells, yeahs!”

Along the way, I gathered some colorful (and sometimes methodically color-coded) stories I’d like to share with you.

A Confession

But first a confession. I’m a careful abstainer, a longtime, diehard member of the Keep It Pristine club.

A conservative approach: My copy of Don DeLillo’s Mao II from the mid-1990s, its tiny shred of Post-it still sticking fast to a passage I loved.

Writing instruments never touch my reading materials. I’ll mark pages and passages with a Post-it, jotting down my thoughts, with their corresponding page numbers, in a notebook. There’s always a crisp roll of Brodart book jacket covers at the ready in my desk drawer. I take care to use bookmarks and never dog-ear. My books are scrupulously clean.

Doesn’t sound like much of a confession, does it?

Well, here’s the thing: I’ve always somehow wished I was the kind of person who wrote in books, who was so full of spontaneous creativity, literary passion and spark that I just had to scrawl all over them. Once, as a teenager, I even tried to deliberately cultivate the habit, but my heart just wasn’t in it and the whole thing felt contrived. As I self-consciously circled and underlined and annotated, all I could think was You’re ruining that book.

A few years working in a used bookstore during college reinforced the No Writing in Books policy for me. There I learned the value (resale and otherwise) of clean pages, tight bindings, and crisp jackets. Still, I’m fascinated by what drives others to make their mark.

Loving Them to Bits

My friend Quintan Ana Wikswo describes herself as “one of those hideous beasts who loves to crack spines.” In a confessional blog post about her no-holds-barred habitual rough-housing of bound, printed matter, she describes one of the more hair-raising book-ravaging indiscretions of her youth. Loving some borrowed library books to bits, she marked them up mercilessly, consuming their pages the way “a drowning rat might gnaw at the cracker he’s floating upon.” The resulting $17,000 library fine, however, was rather sobering.

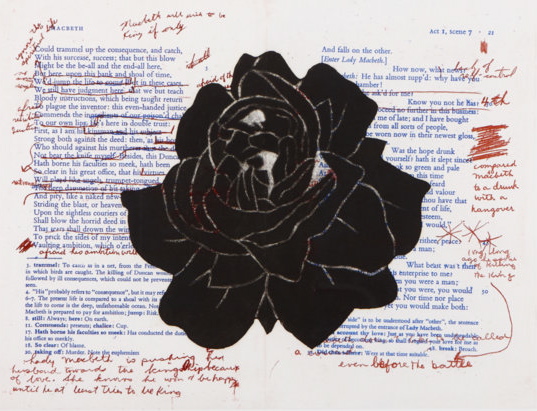

Megan Mayhew Bergman’s copy of Henry Miller’s The Tropic of Cancer, marked up for a class she was teaching at Bennington. (Shhhh, don’t tell Seinfeld‘s Bookman the Library Cop!)

Writer Megan Mayhew Bergman demonstrates a similar visceral love for her books—albeit one guided and tempered by pedagogical practicality: “I underline, make exclamation points, star passages—the more scribbles, the more I’ve loved the book. It makes it easier to return to passages when I’m writing academic or critical work. It’s one of the ways I truly engage with a text, especially if I’m teaching it.”

Marginalia as Time-Travel: Encountering Others (and Past Selves)

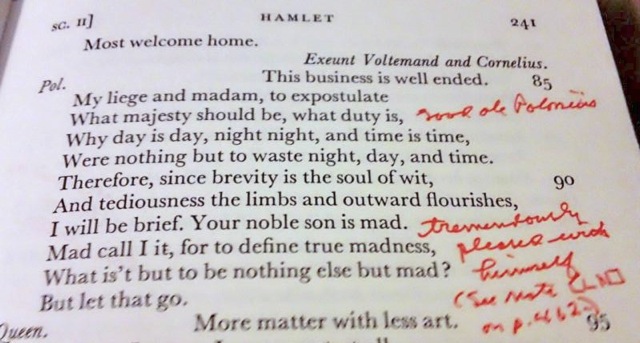

Toni’s Thayer’s late grandfather’s passed-down copy of Hamlet: “Teaching Hamlet for the first time with him sitting there on the page with me was one of the true joys of my life .”

Toni Thayer, a writer and writing instructor based in Cleveland, is also in the love-to-write-in-books camp (are we seeing a trend with teachers here?): “It’s one of the major reasons I dislike eBooks—highlighting and adding comments electronically just isn’t the same… I sometimes teach from books owned by my grandfather, who was an English professor, and I LOVE LOVE LOVE the conversation I get to enter into with him through his margin notes! Teaching Hamlet for the first time with him sitting there on the page with me was one of the true joys of my life.”

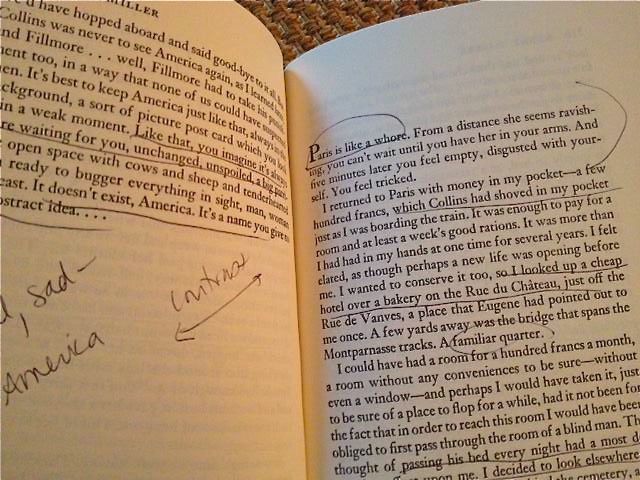

Somewhat less charming, however, are the random jottings of even more random strangers, as noted by my writer friend Laura Catherine Brown: “I really hate buying a used book online only to find it written-in and/or underlined and/or highlighted and/or notated. It’s like running into a gossipy person who shoots his or her mouth off at you when you’re trying to process and form your own opinions.”

Others I surveyed expressed chagrin at re-encountering their own less than brilliant comments scribbled decades ago. Sometimes we really don’t want to get reacquainted with our past selves.

Teenage Daydreams: Doodles, Graffiti, and Fighting the Power

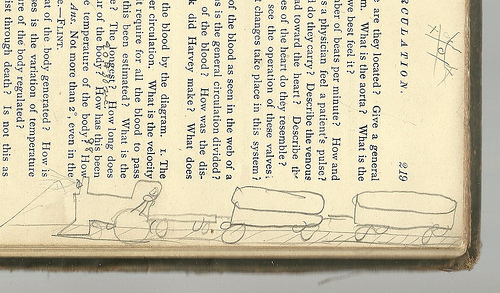

Following a different train of thought: 100-year-old doodles in a textbook on human physiology (image via Ross Griff on Flickr, licensed under Creative Commons)

Call it the graffiti of the book world. Mustaches, glasses, and all those other scribbled add-on, um, appendages. Creative enhancement to Board of Ed-issued textbooks deserves a special category all its own.

I remember being by turns annoyed and entertained by the many “reinterpretations” I encountered in my well-worn and often comically outdated public elementary and high school texts. A recent viral post on Buzzfeed showcases the work of some of that rebellious, covert art’s most accomplished practitioners.

Getting Artful

Not all doodles decrease value. Sometimes a little extra ink can transform an otherwise ordinary book into a hot commodity. For example, Frida Kahlo’s doodled, painted and collaged copy of The Works of Edgar Allen Poe—a worn old copy of a mass-produced book that would otherwise be worth only a few dollars on the market today. With the artist’s enhancements, it fetched over $24,000 at auction last year.

I suppose the writers and artists among us can always dream our own colorful scrawls will someday be so sought-after.

My Precious?/Finding Balance

When I visited artist and hand bookbinder, Regin Igloria, at his community binding space, North Branch Projects, earlier this year, he said something about his hand-bound sketchbooks and notebooks that really stuck with me. I told him I found it easy to write and draw in cheap, disposable notepads, but that when it came to using ones that were made with considerable care and craftsmanship—such as the ones at North Branch—I find it really hard to make that first mark.

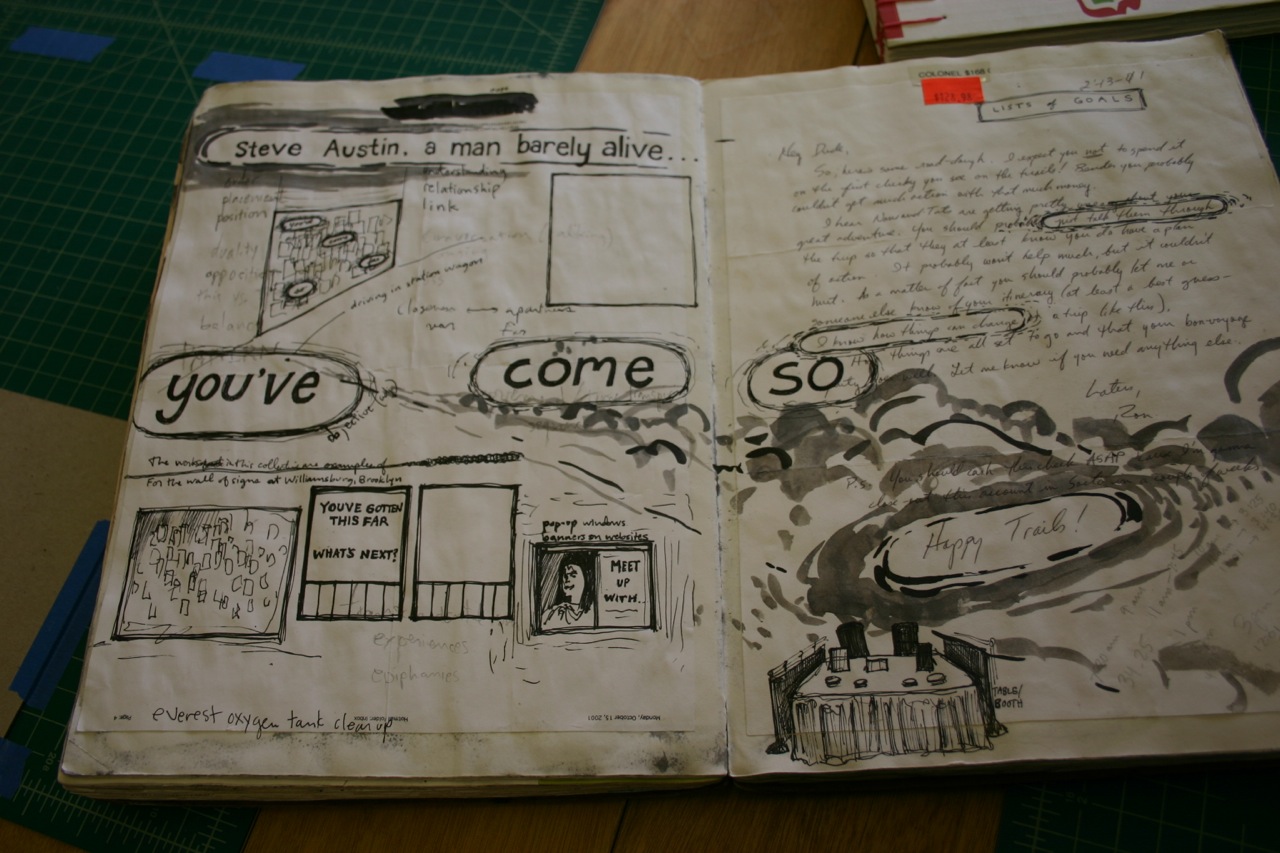

A page from one of Regin Igloria’s hand-bound sketchbooks: “I [wanted] my own students to become less inhibited about putting content into the pages…to lose the preciousness about them.”

Regin said that many others who came to his bindery shared my attitude, but that he’d found a remedy for it, a sure-fire way to break a new blank notebook in: “My drawing teacher at SAIC [School of the Art Institute of Chicago] had us pour coffee or tea in our sketchbooks in order to draw abstractions from them. I went ahead and used his idea to get my own students to become less inhibited about putting content into the pages of our hand-bound sketchbooks, and to lose the preciousness about them.”

Books, like sketchbooks are meant to be used, aren’t they? When I think about that copy of Mao II still sitting on my shelf with its 20-year-old Post-it, I realize I still love that line I flagged, that what makes that paperback valuable to me isn’t its potential for resale, but the words and memories its pages contain. Maybe I should pick up a pencil and mark it now.

Readers, now it’s your turn. Tell us: Do you write in your books? Why? Why not?