Sappho’s Tweets: A New Kind of Fragment

The “Sappho Bot” (@sapphobot) is a Twitter account that tweets a fragment of Sappho every two hours, using the English translations and formatting from Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter. With over 16,000 followers, every single one of these tweets gains traction — often hundreds of retweets. Sometimes it’s just a single word (“honeyvoiced”) or a phrase (“with what eyes?”), and sometimes it’s several lines of a poem:

The “Sappho Bot” (@sapphobot) is a Twitter account that tweets a fragment of Sappho every two hours, using the English translations and formatting from Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter. With over 16,000 followers, every single one of these tweets gains traction — often hundreds of retweets. Sometimes it’s just a single word (“honeyvoiced”) or a phrase (“with what eyes?”), and sometimes it’s several lines of a poem:

And what excites my mind,

Your laughter, glittering. So,

When I see you, for a moment

my voice goes,

What does it mean for an ancient poet and her translator—both women—to be taking up this kind of space in our ‘timelines’? How is this bot interacting with the long history of Sappho’s work undergoing fragmentation and ruin?

The aesthetics of ‘ruin’ in its different manifestations are so attractive and interesting to readers and writers that we now have a whole contemporary poetic genre of ‘erasures’ or ‘blackouts’ from other texts. But the idea that ruin or brokenness might be inherently beautiful bears a lot of gendered baggage, especially considering the way we value female sexuality in real life as well as in the literary imagination. While thinking about Sappho and ruin is nothing new, the phenomenon of the Sappho Bot lends new layers to the discussion.

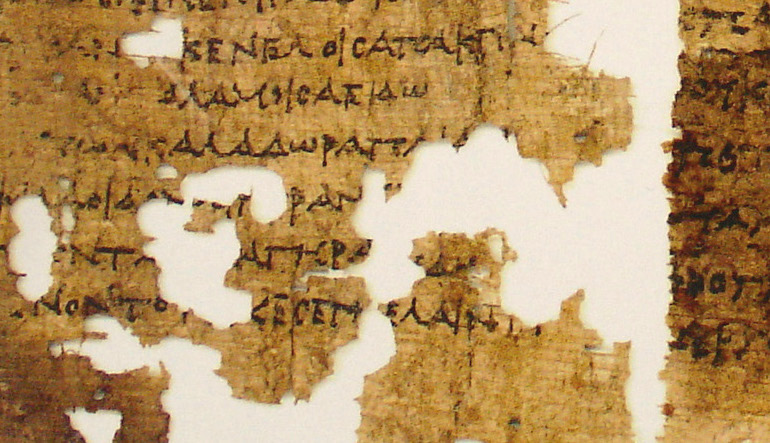

In order to examine how the Sappho Bot engages with the idea of the fragment, it’s important to first consider the source text—not the hundreds of fraying pieces of manuscript that make up the known Sappho canon, but the actual text that the bot is using: Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter, an English translation published side-by-side with transcriptions of the original Greek in 2002.

What does it mean to compile Sappho into a book? Anne Carson’s translation does more than just swap Greek words for English ones: it sets Sappho’s fragments into the format of a single book. It’s neatly bound between covers, safely cushioned by an introduction on one side and an appendix on the other. It is a whole. The word ‘codex’ sounds ancient and mysterious, but on a basic level, it refers to the method of binding pages together between covers, to make a text into a single, tangible object.

If Not, Winter streamlines the fragments of Sappho into an (unavoidably) phallic structure of linearity and singularity, yet the fragments are nonlinear by nature. Additionally, consider how the book represents the combined labor of a female poet and a female translator, plus the implicit inputs of classicists, archaeologists, and archivists of the past who have contributed to finding and identifying partial manuscripts over the centuries. Even before crossing into digital space, the project is already fractured across time, space, and genders.

But Twitter is not a codex. In a way, Sappho has been returned to the ‘scroll’: that verb we use to describe continuous movement on digital platforms finds its origin in a noun, the scroll, an older form of reading where the reader has to carefully turn the handles on either side in order to reveal more of the rolled-up text.

When the Sappho Bot breaks up If Not, Winter into tweets, divorcing the lines from what little context there was to begin with—no more introduction, no more appendix—we have a new kind of text: broken pieces of a reassembled ‘whole.’ Digital texts are not subject to the natural weathering of plant-based paper, but they do open up new horizons for how we think about taking up space and the spaces that marginalized genders can or should occupy. Within the constant stream of news and opinions, it can be startling to come across a tweet mostly characterized by blank space. For example:

Holy and beautiful

maiden

around[

]

]

]

to be

]to arrive.

These brackets, according to Carson’s introduction to If Not, Winter, indicate “destroyed papyrus or the presence of letters not quite legible somewhere in the line.” They also invoke a sense of ghostliness—a trace of the missing text, which was always already lost before any English translation could have been attempted. The gesture, transferred into the ephemeral space of the Twitter timeline, signifies the right to occupy space even in the face of a perceived lack.

Sappho’s work has faced many other forms of ‘ruin’ besides those associated with the physical words. Editors and translators have historically skewed the homoeroticism of her lyrics, either to increase the taboo quality of the work or, on the other extreme, to entirely discount female sexuality and queerness from their interpretations. It can also be tempting to romanticize the fragmentary nature of the Sappho canon; pining for what is lost feels inherently poetic, and the lost material itself becomes an object of desire.

But women have never benefitted from the fetishization of brokenness, and neither does Sappho’s work. It’s important to keep in mind how valuing the brokenness of the fragment can spill over into harmful territory, such as romanticizing trauma. Even the general concept of ‘ruin’ has become gendered as feminine through social constructs of virginity. Texts and bodies have always been inextricably linked, and that doesn’t change in conversations about brokenness.

Digital spaces are excellent for exploring new modes of literary fragmentation, but we have to explore mindfully. When we engage with innovative forms of literature like the Sappho Bot, it’s important to stay cognizant of how the dynamics of fragmentation and ruin are always interacting with the way we approach social issues in our own time.