The Beasts of Kenzaburo Oe’s Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids

“To them, we were complete aliens.” So begins the first attempt by the unnamed protagonist of Kenzaburo Oe’s Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids to define himself and his fellow reformatory boys in wartime Japan. His last attempt is this: “I was only a child, tired, insanely angry, tearful, shivering with cold and hunger.” Like so much of Oe’s work in this agonizing fable-disguised-as-novel, such deceptively simple sentences pack a hard punch. This is a story of how children suffer graphic violence at the hands of adults, but it is also a tender, romantic coming-of-age.

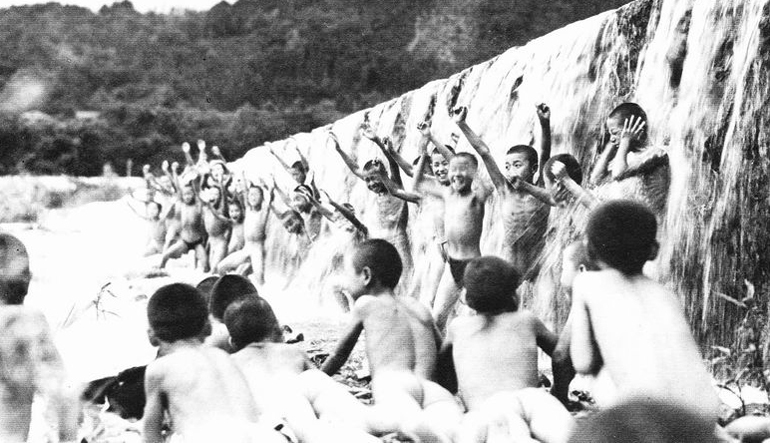

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids glazes over the specifics of time and place on purpose to give the novel a sense of the surreal, though implicitly it occurs during World War II as it was experienced by Oe in his youth. “It was a time of killing,” Oe writes. “Like a long deluge, the war sent its mass insanity flooding into the convolutions of people’s feelings, into every last recess of their bodies, into the forests, the streets, and into the sky.” He portrays war as a force that transforms people into “maddened adults” with a “strange mania for locking up those with skin that was smooth all over, or with just a little chestnut down; those who had committed petty offenses; including those judged simply to have criminal tendencies.” It’s clear from context that this is a description of the fifteen reformatory boys central to the story. As part of the evacuation of school children to rural areas, the reformatory boys are sent on a forced trek to an isolated village in the mountains. The brilliance of this novel lies in Oe’s uncanny transformation of these boys into absolute outsiders who can find compassion only from other outsiders: a Korean boy, a deserter, and a girl whose mother dies in quarantine from tetanus (lockjaw).

Oe explores a common question and concern: “What gives us our humanity?” The answer comes most often via a mob mentality, but the protagonist continually undermines that response with his observations of beautiful expressions of humanity hidden in circumstances of absolute cruelty. The main difference between these two responses is power. The power to define what it means to be human rests, most of the time, with adults who are too caught up in an atmosphere of violence, death, and war to remember that their scapegoats are little boys.

Oe sets up the reader by allowing his protagonist intentionally to push away the reader early in the novel. The reformatory boys say and do provocative, inappropriate, and sometimes disgusting things, often expressing their own lust for violence, such as in these disparate moments from the first third of the novel:

Some of us went up to the hedge, flaunting immature penises like reddish apricots at the villagers.

… Hunting: the silent hunt of villagers bearing spears and hoes; the soldier pursued, running through the wood and drowning in the flooded valley. We sighed deeply, plunged in the bloody image of hunting which shook our bodies. We were really in the maelstrom of war. And a stupefying crisis, like a beast, was nosing its dark head toward us. Ah, hunting.

… The stink which gushed out [of the pile of animal carcasses], twisting and twining, was impregnated with something that tantalized us. Children who have sniffed eagerly with their small noses pressed up against the hindquarters of a bitch in heat, children who have the courage and reckless desire to enjoy, even for a short while, the dangerous pleasure of rapidly stroking the back of an aroused dog, can recognize the subtle human signal and allure in the stink of animal carcasses. We opened our eyes wide, fit to burst, and inhaled lustily.

If the response of the reader to these comments is revulsion or disgust, that’s to be expected. The protagonist is treating readers as if they are in league with the adults who have so harshly ostracized them with poor food, circumcision, and beatings.

The only boy to be regularly excluded from such self-degrading comments is the protagonist’s little brother, an innocent child offloaded by their father at the reformatory school during the evacuation. The little brother brushes with violence over and over throughout the novel, but is never corrupted by it. This is true not only of his interactions with the other reformatory boys and adults but even of his interactions with animals and nature. When he befriends a dog infected with the rabies virus, for instance, he is able to play with the dog unharmed. It “licked my brother’s neck and cheeks and nipped his shoulders and arms,” the protagonist tells us, but it doesn’t bite him. Yet, in a novel packed with violence, even this “angel” cannot avoid tragedy in the end.

In spite of the protagonist’s wistful love of his innocent brother, the emotional punch of this story ultimately belongs with him. The protagonist may not be innocent, but he’s a brave and generous person who attracts all other outsiders to him. He is the one who accepts a Korean boy abandoned by the villagers into the reformatory boys’ inner circle. He is the one who helps a young girl overwhelmed by grief. And he is the one who shares intimacy with the military deserter. He sees and admires the humanity of each of these individuals, and his experiences with them prepare him to make a choice in the final pages of the book that asserts his own humanity when the adults want him to accept shame and cowardice. Yet he frames his own decision simultaneously as a child and as a beast, seeing himself as both at once. Readers, left with the image of a child fleeing like a beast “from the brutal villagers,” can see for themselves that it is the one pursued, not the hunters, who captures what it means to be human.