The Beauty of Self-deprecation in Andrew Miller’s IF ONLY THE NAMES WERE CHANGED

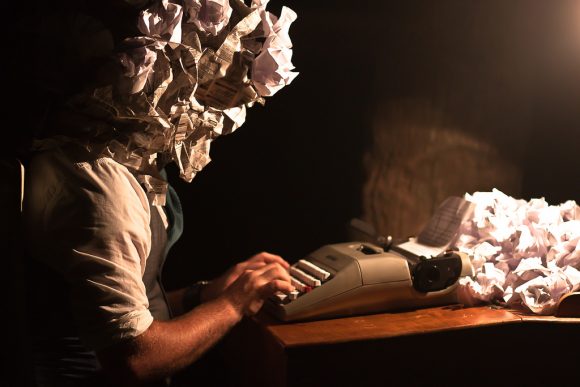

Fasten your seat belts. Andrew Miller’s alternative lit style is about to take you on a bumpy ride. His memoir in essays, If Only the Names Were Changed, vacillates between hyper-masculine and tender in terrain that traverses parental concerns about raising a daughter, drug and alcohol abuse, and how much of a jerk he is.

A host of literary influences appear throughout—the aggression of Henry Miller, the thumbing of conventionalism from William Burroughs, and Lauren Slater’s questioning of truth. Let’s consider the Slater approach. Miller addresses that some facts may not easily be remembered because of his chemical and alcohol intake over the years. Like Slater, he admits that some of the tales may be fiction.

“I know that I’ve lied a lot throughout these pieces. A lot, to both the characters and you, the reader,” he writes. “I also know that I’ve lied to myself, not just in writing but in life.”

Sometimes truth is hard to find not because of mind-altering substances or a forgetful memory. Sometimes it’s hard to know the essence of something, its real truth. In that sense Miller’s essays speak with a universality that we humans can understand as we try to unpack the existential kernels of life.

This is evident in the second essay of the book, “House of Leaves,” in which Miller’s trying to suss out just how much of an asshole he is. It’s a frantic piece. It sways like a roiling ship from action to action.

I listen to “White Riot” on repeat and Joe Strummer asks me if I’m doing just what I’ve been told.

If I’m taking over or just taking orders.

If I’m going backward.

I’m going backward.

And then I think I am meant to be a revolution to myself.

One moment he’s riddling himself with bullets of self-deprecation for being a “good kid” and “ass-kissing” in his youth. He reaches out for confirmation, such as when he’s shooting emails back and forth with a friend:

I’m an asshole. That’s what I’m writing about. I’m an asshole and I feel like I need to deal with that and understand it.

When his friend basically tells him it’s a matter of perspective, the tension falls away like a trap door in the floor and tenderness rushes in to take its place. The prose quiets, softens as he quietly comforts his daughter post-nightmare:

As she falls asleep once more I sit there in quiet contemplation over whether I’m protecting her or just stubbornly hiding from my own fears.

Beyond the tension and the essayistic sojourns, Miller uses fragments of poetry and fiction, sketches of political dissertations, and computer screen shots. Together these hybrid forms contribute to an alternative nonfiction style. He presents multiple examples of this in “Where’s the Octopus?” Sometimes he creates scenes that read like fiction.

Sometimes the lines flash by in a series like poetry.

I need to spin to continue to craft my narrative.

I need double entendre.

I need word tricks and time travel.

He articulates thoughts as a single line followed by another single line followed by another to form fast, often frantic, poetic rhythms. The effect demonstrates his racing thoughts.

As he continues in this section, the reader can relate this frenzy from our own tech-and-info-overloaded days.

I post to my feed.

I don’t feel overwhelmed.

I feel in control.

It’s an illusion.

In “On Our 60th Wedding Anniversary,” Miller dares readers to keep up. This essay volleys back and forth thoughts on aging and anxieties of planning a wedding. The reader feels the tension of comparing regrets and sadness from the past with anxieties for the future. Throughout this essay a thread connects the past and present. It brings forth a calm after the gnashing, rebellious past essays via the memory of his grandfather.

My grandfather gave me little pity figuring this was a lesson to be learned: focus, attention and patience. He, however, swung his hammer true, hanging out the stringers and toe boards, and securing each tread with no split out.

Altogether Miller’s book is full of topics indicative of a middle-aged author from child rearing and self-deprecation, trying to be a better husband and father, dealing with youthful mistakes that have left lingering effects, and reworking personality flaws. It’s easy to get deep into the psyche of an author who uses poetry and screen shots and fictional techniques and existential questioning on his journeys through essays.

Civil Coping Mechanisms, a publishing arm of Entropy lit mag, published this 186-page title in June 2016. Miller also has a book of poetry, You Must Know This.