The Bottom of the Mere

Guest post by James Arthur

I’d like to think that although poetic styles change, as they should, the themes of poetry are more durable: that poets will keep writing love poems, for example, as long as romantic love exists, and writing elegies as long as there is death, because poetry reflects human experience, and the parameters of human experience are themselves durable.

But lately, I’ve started wondering whether people might someday build a world containing so little wilderness–so little territory beyond the control of human beings–that any poem about a wild place would seem quaint. The Beowulf-poet, in Heaney’s translation, writes:

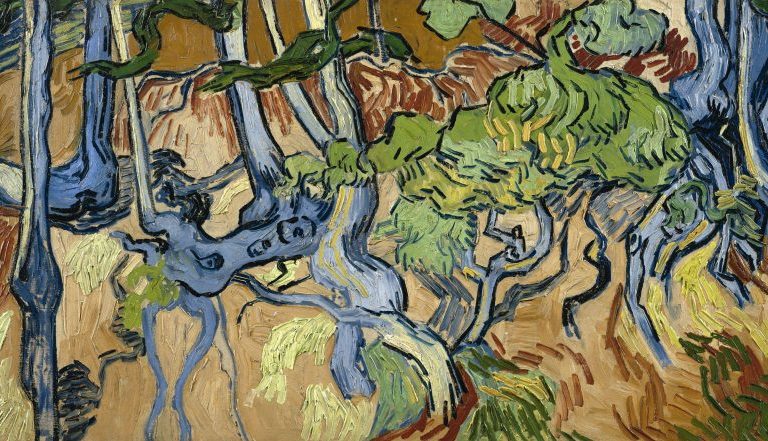

A few miles from here

a frost-stiffened wood waits and keeps watch

above a mere; the overhanging bank

is a maze of tree-roots mirrored in its surface.

At night there, something uncanny happens:

the water burns. And the mere bottom

has never been sounded by the sons of men.

… And I can’t help but feel, despite Heaney’s graceful rendering of the original, that something–a sense of dread, maybe–has washed out of the lines, now that we as a species actually have sounded the bottom of almost every lake and pond. There are very few implacable wildernesses remaining on Earth, so will they disappear from poetry, too? And what if we, like the empire-builders in Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians,” require the existence of something we cannot dominate?

The question sent me rooting around in an essay that I love but hadn’t read for years, “Baler Twine: Thoughts on Ravens, Home, & Nature Poetry,” by Canadian poet Don McKay. A few pages into the essay, McKay remarks, “By ‘wilderness’ I want to mean, not just a set of endangered spaces, but the capacity of all things to elude the mind’s appropriations.”

Wilderness, as McKay defines it, is everywhere and cannot be exterminated, because it is the alienness and ungovernability existing even in objects we think of as our possessions: existing, for example, in the slow disintegration of a wooden chair. Nature poetry, for McKay, is an attempt to praise and translate this alien quality, with the understanding that being translated, being made into an artifact, is antithetical to the very nature of wilderness.

What would such poetry look like? Well, like Don McKay’s poems, of course, which I highly recommend. I also thought of Les Murray’s 1992 collection Translations from the Natural World, full of gruesome pleasures like “The Cows on Killing Day”: poems that find wilderness in domestic environments and, better yet, have the good sense not to sentimentalize their subject matter by making it familiar.

This is James‘s second post for Get Behind the Plough.