The Destruction of the World in Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead

In Olga Tokarczuk’s newly translated novel, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Janina Dusezjko’s neighbors keep turning up murdered. The police do a terrible job of looking into the deaths, and Janina tries to help them out by writing long, increasingly insistent letters about the suspects being ignored. The culprits, she says, are the wild animals of the snowy Polish plateau that she calls home. The victims were all hunters on the plateau, and in each case they have been surrounded by the fingerprints of animal kind. As far as Janina understands, the hunted are taking their rightful revenge. Originally published in Polish in 2009, Tokarczuk’s novel, published last month in English after translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, has been marketed as a murder mystery, albeit a strange one. It is that, partly, but underneath the whodunit is another novel: one about how our obsession with usefulness leads to greed, and the devastating impact of both on the environment.

Janina likes to keep busy. Somewhere in between letter-writing, horoscope calculating, and checking on her neighbor’s houses, abandoned for the winter, Janina meets and befriends an entomologist named Boros. One day, as they are walking through the woods together, Janina asks Boros which of the beetles he has been pointing out to her are useful. The entomologist snaps at her, saying, “‘From nature’s point of view no creatures are useful or not useful. That’s just a foolish distinction applied by people.’” Later, Janina ponders the implications of this distinction: “Does a thistle have no right to life, or a Mouse that eats the grain in a warehouse?” she asks. “What about Bees and Drones, weeds and roses? Whose intellect can have had the audacity to judge who is better, and who worse?” Tokarczuk understands the insatiable drive we all feel to look for the usefulness in others above all other traits. But, she reminds us, this is a terrible way to see each other. More importantly, it is the driving force behind humanity’s destruction of the natural world.

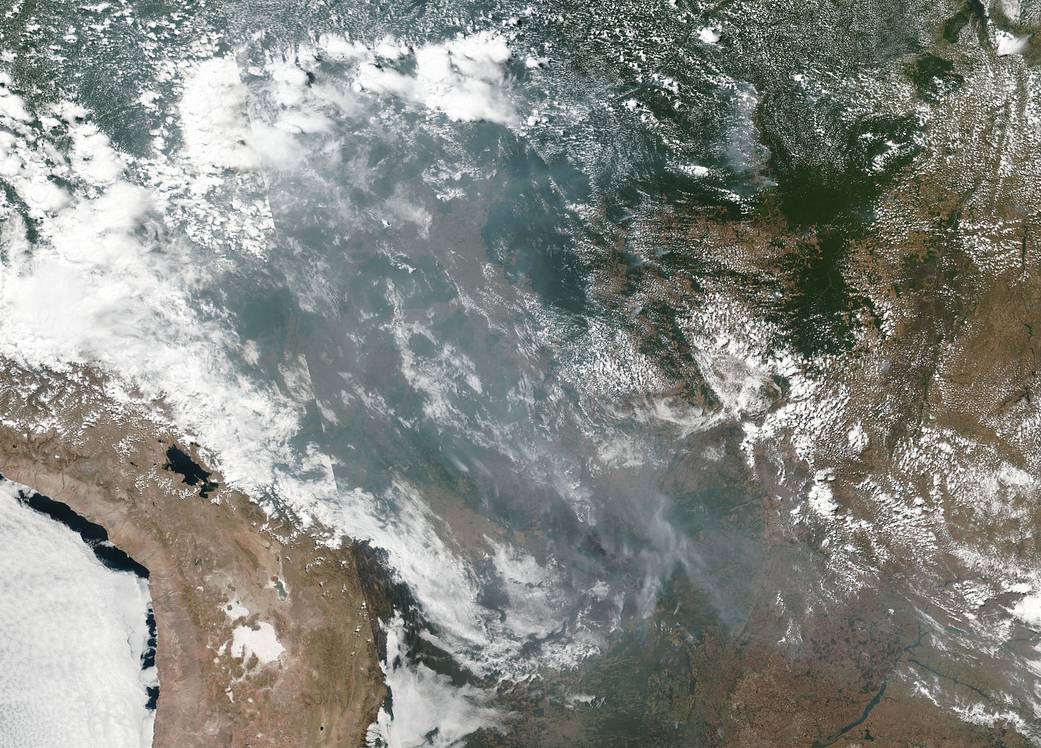

The novel’s Polish release predated the newest and most apocalyptic visions of climate change—the ones that really keep us up at night. One of the many horrors on our minds these days is the burning Amazon rainforest, which is being clear cut and set aflame to create space for farmland. Brazilian president Bolsonaro has been famously smug about the whole thing, and Trump is, of course, behind him one-hundred percent. Such capitalist villains stick together. Last October, when Bolsonaro took office, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation ran an article titled: “What a far-right Bolsonaro presidency in Brazil means for Canadian business.” It included the statement that “a Bolsonaro presidency could open new investment opportunities . . . as he has pledged to slash environmental regulations in the Amazon rainforest.” Countless generations have been blinded by visions of the usefulness of some natural resource or another; in our time, we are privy to a darker truth: people can be blinded in this way even when it threatens all human life on earth. All of us seem capable of a kind of depraved ambivalence. In Tokarczuk’s novel, as in life, depravity can be excused by saying that what you are doing is useful.

At the end of her own long struggle against the hunters on her plateau, Janina sits in on her town’s dedication of a chapel to Saint Hubert. Saint Hubert, Tokarczuk tells us, is the patron saint of hunters, despite the fact that his moment of spiritual revelation came when he realized that he should stop hunting. During the chapel dedication, the town’s priest (who is also chaplain to the town’s hunting club) takes the pulpit and gives a sermon to the effect that “‘hunters are the ambassadors and partners of the Lord God in the work of creation, in caring for game animals, in cooperation.’” If all of this sounds too contradictory to be anything other than satire, Tokarczuk’s author’s note will sober you: she notes that the priest’s whole speech is a compilation of genuine hunt chaplain sermons. The priest goes on to list the many things that the hunters have done to support the wildlife in the area: they built feeders in the area for deer and pheasants, and keep them stocked. “‘And when the Animals come to feed,’” Janina says, “‘they shoot them.’” Of the people in town, she alone is unconvinced by the appeal to usefulness.

Janina realizes that she, and each member of her small circle of friends, are people whom society regards as useless. There’s Dizzy, an ex-student of hers who diligently translates William Blake; Good News, who runs a tiny thrift shop; and Oddball, a meticulous older man who spends most of his time organizing his tools. “I’m like them, too,” Janina says. “My life’s harvest is not the building material for anything, neither in my time, now, nor in any other, never.” But again, she takes up what might be considered the mantra of the book, asking, “Who divided the world into useless and useful, and by what right?” Of course, Tokarczuk has already given her answer to this question, earlier, in the words of Boros the entomologist: people divided the world in this way. People gave themselves the right.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead takes its title from Blake, from one of the poems that Dizzy and Janina have translated together, called “Proverbs of Hell.” The poem reads: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. / Prudence is a rich ugly old maid courted by Incapacity. / He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.” Together, the proverbs are a kind of satanic boast, focused on human power and the right to pleasure-taking. Blake is a constant fixture throughout Drive Your Plow—short couplets of his precede each chapter, and there are several scenes devoted to watching Janina and Dizzy translate. Despite all of this attention paid, Janina admits to not being quite sure what to make of him: “I couldn’t make head or tail of the beautiful, dramatic images that Blake conjured up in words.” In fact, Blake introduces contradiction into the terms of the novel. Towards the end of “Proverbs of Hell,” there is a line that seems to contradict Janina’s perspective entirely: “Where man is not nature is barren.” The poem is from a larger work of Blake’s, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, which is, at its core, about contradiction. Hell encourages revolt, and Heaven order. Somehow, Blake argues, we each need to find our balance between the two. It is impossible to be a human and not look for what can help us thrive. But it is difficult to look constantly for what we can take without harming the people and world around us. In Tokarczuk’s terms, people give themselves the right to determine what is useful, but we also give ourselves the power to decide when we (and others) have taken enough.

Is there anything that can withstand the onslaught of our search for utility? In describing her “useless” friends, Janina gives us her answer: “A large tree, crooked and full of holes, survives for centuries without being cut down, because nothing could possibly be made of it. This example should raise the spirits of people like us. Everyone knows the profit to be reaped from the useful, but nobody knows the benefit to be gained from the useless.” Until the “useless” are all gone, we might add, from our perch at the end of the world.

This piece was originally published on September 12, 2019.