The Funniest Writer You’ve Never Read

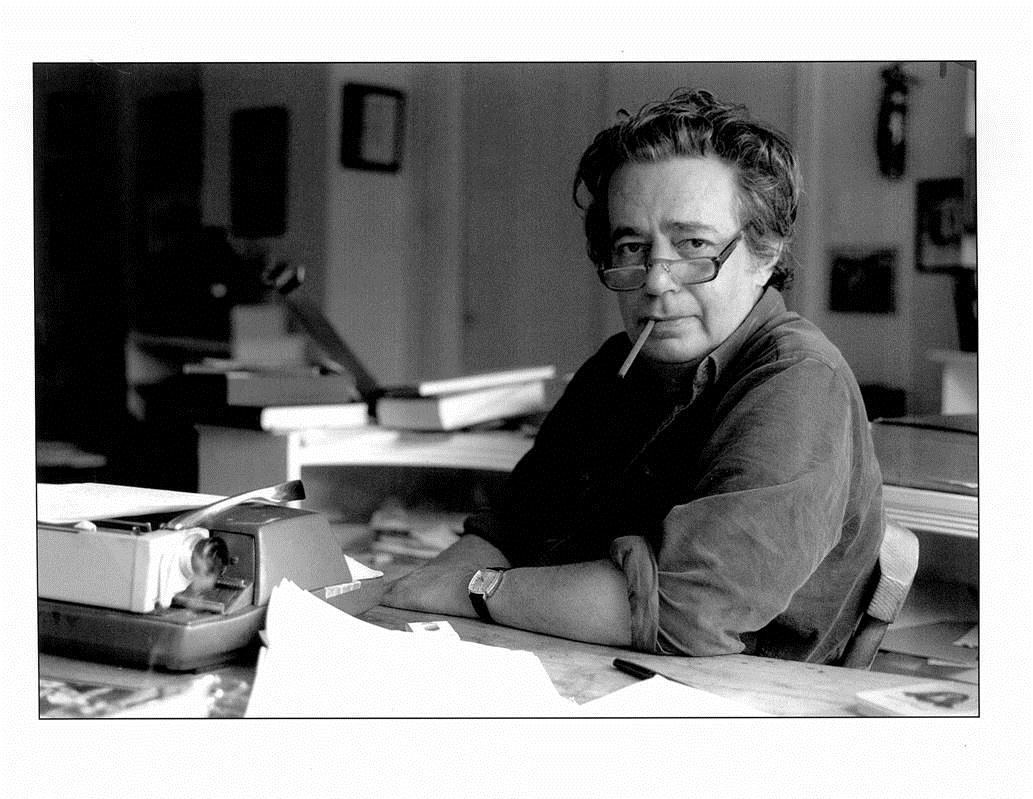

The funniest writer you’ve never read is a deceased Canadian named Mordecai Richler. The author of ten novels, a short story collection, and several books of essays, Richler was—and is—hugely famous in Canada. That he is not well known in this country is possibly a product of our curious parochialism as American readers.

The funniest writer you’ve never read is a deceased Canadian named Mordecai Richler. The author of ten novels, a short story collection, and several books of essays, Richler was—and is—hugely famous in Canada. That he is not well known in this country is possibly a product of our curious parochialism as American readers.

I’ll begin where Richler himself might have—with his flaws.

One part Philip Roth, one part Borscht Belt, one part wholly original scrapper from the Jewish ghetto of Montreal, Richler was a divisive figure, a gimlet-eyed satirist who spared no one. The first line of his obituary in the New York Times called him “cranky and combative,” a send-off to aspire to. “Over a long career,” the obit goes on, “he infatuated readers on two continents and managed to offend nearly everyone in some way.”

Everyone, it turns out, refers mostly to Québécois nationalists, the Jewish population of Montreal’s Mile End, and the same prim, mid-century audience that clutched its pearls at the liver scene in Portnoy’s Complaint.

What’s more, Richler took aim at the homogenous, boosterish quality of state-sponsored Canadian literature. In his 1968 essay collection Hunting Tigers Under Glass, he summed up Canadian writing thus:

In a typical play, a sensitive little twerp named David or Christopher, usually son of a boorish insurance agent, roused his dad’s ire because he wouldn’t play hockey or hit back…and in the end made his dad eat his words by winning the piano competition in Toronto or, if the writer was inclined to irony, by being commissioned to paint a mural for the new skyscraper being built by the insurance company dad worked for.

Offended yet? Well, his novels are also often sexist, in that mid-century, “woe to castrating feminists” way (although, if we don’t occasionally look past that particular foible we’ll never be able to crack a novel from that era again).

Still—still!—Mordecai Richler is well worth reading. Why? Wells Tower once wrote of Barry Hannah that “any one of [his] sentences picked at random holds more hope and joy than the entire self-help section of the O’Hare Barnes and Noble.” I think the same is true of Richler, whose enduring strength is his voice. Years after his death, his work remains full of life.

So where to begin? How about with this warm and wry 1965 Holiday Magazine essay about the legendary hotels of the Catskills? Or you could start with his breakout novel, 1959’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which contains most of the components of his best work: a striving narrator, a rags-to-riches story, a spirited scrum with Jewish-Canadian identity.

My own introduction to Richler was through his final novel, Barney’s Version (1997), a footnoted confession by the declining Barney Parnofsky. “Terry’s the spur,” it begins. “The splinter under my fingernail. To come clean I’m starting on this shambles that is the true story of my wasted life…” The book was made into a film in 2010. That it managed to be mediocre, despite turns by Paul Giamatti and Dustin Hoffman as father and son, is a testament to the singularity of the novel’s narrative voice. Plus, footnotes translate badly to celluloid.

An equally excellent entry point is 1989’s Solomon Gursky Was Here. A sprawling, multi-generational tale of a rich, Jewish family with magical realist overtones, I’ve heard it referred to as One Hundred Years of Jewish Solitude. In one of my favorite sequences, the eponymous Gursky finds himself in the Arctic, converting a group of Inuits to Judaism. Things go awry on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, when adherents fast until sundown. In the Arctic, of course, the sun doesn’t set for months at a time.

Richler died in 2001 of kidney cancer. It took fourteen years, but last month, he was finally honored with a library in Mile End. Before that, Montreal had tried to name an alley after him. When that didn’t work out the city settled on a gazebo. The gazebo grew increasingly dilapidated. Eventually the floor rotted out. Richler would’ve liked that, I think.

About Author

Erin Somers' writing has appeared in One Teen Story, The Rumpus, Gigantic, and elsewhere. In 2013 she was awarded the Neil Shepard Fiction Prize from Green Mountains Review. She lives in Brooklyn and you can follow her on Twitter at https://twitter.com/SomersErin.