The Innocents Ashore: Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore Turns Forty

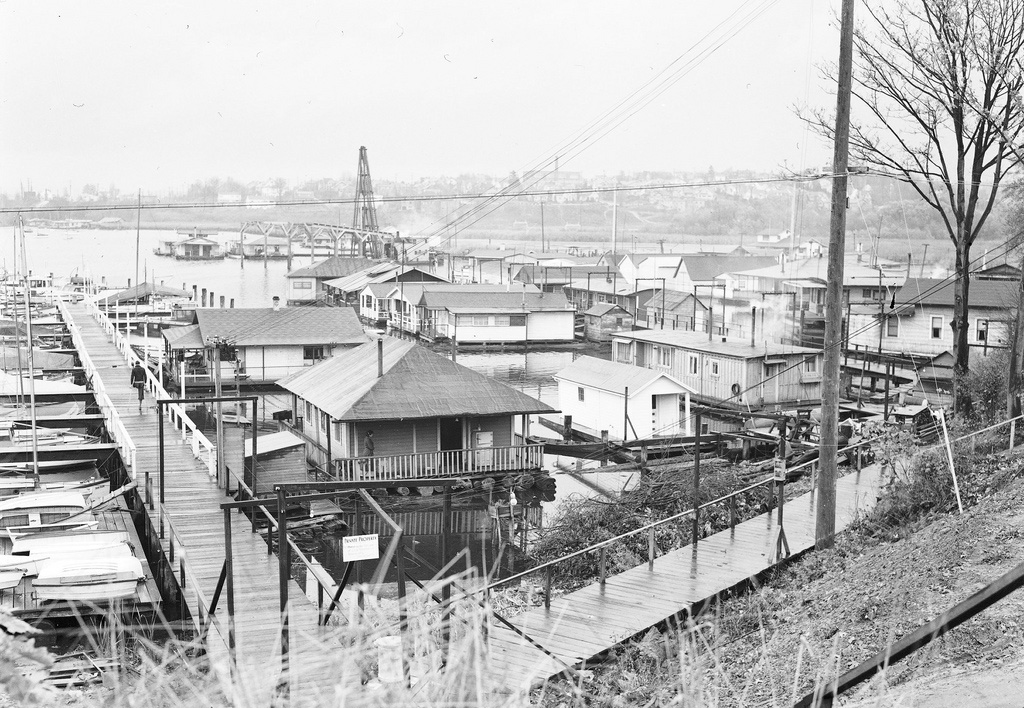

Forty years ago, a little-known British writer published a slim volume that went on, miraculously, to win the Booker Prize. Its lucid, almost stringent prose, coupled with its curious subject matter—the lives of houseboat dwellers living on the Thames—brought the work of Penelope Fitzgerald, then already in her sixties, to wide attention. And while today Fitzgerald might be more well-known for her later works of minutely realized historical fiction, including 1995’s The Blue Flower, the charm that Offshore offers is still abundant; its sensitive limning of emotional climate and its crisp, distilled style provide a captivating introduction to Fitzgerald’s work.

Like many of Fitzgerald’s novels, Offshore is a work of withering, focused on slow declines. Its characters are unmoored, either just past the main arc of their lives or already deeply ensconced in their particular failures, concerned only with staying afloat. To put it simply, they are well-practiced in what the novel’s narrator shrewdly calls “the art of hanging together.”

Perhaps more than any of her other works, Offshore manages to embody, in its initially on-the-nose setting, the complexity of Fitzgerald’s style and concerns. The in-between space of the river’s edge acts as a scenic parallel to her spectral blend of humor and muted drama, while the effect of her narration, which hovers wryly over the story, alternating between piercing insight and elision, mimics the fundamental motion of the novel—an uncertain rocking between land and sea, hope and resignation.

The novel centers on a group of misfits living on houseboats at Battersea Reach, an inlet of the Thames, in 1961. The book’s ostensible protagonist is Nenna, a young mother of two precocious children. Her husband, Edward, having spent a year in South America on a money-making venture, now refuses to live on the houseboat that Nenna purchased in his absence. Though there’s not much of a plot per se, the chief drama of the work largely derives from Nenna’s vacillating relationship with Edward, and her unwillingness to fully commit to reconciling with him.

Besides Nenna, the novel is peopled with a rogues’ gallery of failures, individuals attempting to ride out the time remaining to them in some semblance of productivity and usefulness. There is, for instance, Maurice, a gentle neighbor who survives on the subsistence wages he makes as a male prostitute; Willis, a bedraggled old maritime painter who’s seen the demand for his works decline steadily since the war’s end; and Richard, the vaguely patrician, de facto leader of the Reach-dwellers, who once served as a volunteer in the Royal Navy and whose wife has grown increasingly fed up with his interest in house boats.

Fitzgerald’s barge-dwellers, we learn, are “creatures neither of firm land nor water,” marked by “a certain failure…to be like other people,” a flaw that causes them “to sink back, with so much else that drifted or was washed up, into the mud moorings of the great tideway.” For Fitzgerald, failure is just such a globby pit, a terrene hell where her characters, in the words of Baudelaire, lead lives “unfolding with insensibility.” Their lives have a leftover, shadowy air about them, as though their figures have already begun to fade from the world, the only things still anchoring them are a collection of half-baked plans and baseless hopes—the dreamy, anodyne prophecies they tell themselves, perpetually, in order to go on.

Despite this central inertia, Offshore is ultimately a novel of overturnings. Throughout the work, Fitzgerald is at pains to chart the destabilization of domestic space, class distinctions, and even simpler boundaries. Time and again the characters and their boats are shown to be undergoing a process of fusion, gradually taking on each other’s traits. The inhabitants of the Reach feel “the patches, strains and gaps in their craft as if they were weak places in their own bodies,” and the barges themselves, when the tide rises and raises them, release “groans that seemed human.” This patching process is an integral part of Fitzgerald’s fiction—just as the boats, all in various states of labefactation, undergo their necessary repairs, so too does the body. “The body must either repair itself or stop functioning,” Fitzgerald writes at one point, “but that is not true of the emotions.” Her characters, as we all do, trail a tattered emotional patchwork that grows more raggedy with every passing day—the sum total of all their heartbreaks, fears, joys, regrets, stitched and patched and taken in and reworked constantly, until it’s as ugly and piebald as a blanket made of rags.

Part of the domestic sphere’s overturning is fairly literal. In the novel, Willis attempts to sell his boat in order to make a little last money to die on, but it sinks before he’s able to finalize the transfer. One evening he has guests over for dinner and goes down into the hold only to find it filled with river water. As in a fairytale, the domestic becomes violent, hostile. His bunk, floating now in the murky, fetid water, rams into his shin: “That, for some reason, almost made him give up, not the pain, but the familiar bit of furniture, the bed he had slept in for fifteen years, now hopelessly astray and as it seemed attacking him. Everything that should have stood by him had become hostile.”

In a more figurative sense, Nenna’s arc charts the decline of a traditional domestic paradigm. When Edward returned from his trip to South America, which occurs before the novel’s opening, he steadfastly refused to live on the house boat Nenna had purchased, and never even went to see it. Over the course of the novel, Nenna, who’s yet to see Edward since his return, occupies her mind by thinking of the rebuttals she might make to his still largely hypothetical objections—it won’t be bad for the children; in fact, the waterside is an excellent place to play; they’ll be busy so often, which will in turn solve the problem of lovemaking in such a confined space.

Fitzgerald is a fan of irresolution. There’s a tendency for her characters to communicate in gestures because they have such a tenuous grasp of their feelings and motivations. It’s never quite made clear, for instance, why Nenna felt the need to buy the house boat in the first place, besides the simplest and probably most apt explanation: that she did not know what to do, and thought it might be nice. Similarly, in her climactic fight with Edward, when her confusion is at its greatest, she resorts to a gnomic utterance: “‘Please give.’” When Edward asks her what exactly she wants him to give, she replies, “‘Give anything.’” The narrator’s commentary follows shortly after: “She didn’t know why she wanted this so much, either. Not presents, not for themselves, it was the sensation of being given to, she was homesick for that.” The typical Fitzgeraldian tête-à-tête is a string of faulty communication, of missed connections, of vague desires mistranslated into words.

Fitzgerald is the sovereign poet of those indefinable moments in life when one is confronted with a last opportunity, a final chance. In Offshore, the possibility of change, of a salvific shift in the trend of one’s existence, is so often beyond the scope of the characters’ minds that an interesting motif, that of salvaging, springs up around it. While the glutinous terrain of the riverside naturally traps bicycles and shopping carts and old brittle crates, it also harbors hidden treasures, gleaming fragments of other, more composed existences. When the sun begins to slip in the sky and its rays hit the earth at an angle, “striking fire out of the broken bits of china and glass” that stud the morass, Nenna’s children, Tilda and Martha, go scavenging. Tilda, nimble and fleet, poised like a triumphant corsair atop the handlebars of an old bicycle, snags two tiles from the muck, and together the girls wash them off with water from a nearby standpipe:

As the mud cleared away from the face of the first tile, patches of ruby-red lustre, with the rich glow of a jewel’s heart, appeared inch by inch, then the outlines of a delicate grotesque silver bird, standing on one leg in a circle of blue-black leaves and berries, its beak of burnished copper.

These felicitous finds represent the novel’s mechanism of salvation. This system of broken, disarticulated objects—the particles of another life, one of domestic wholeness, with a gleaming kitchen, a tiled backsplash, burnished copper pans dangling from a wooden beam—won’t be reconstituted. For Nenna, as for the other residents of the Reach, a complete reversal of fortune is out of the question; redemption, if it comes at all, is fortuitous—it is simply to be plucked from the muck, to be held up to the light and valued for a moment.

Accordingly, a strange sense of possibility and openness closes the novel. At the end, Nenna is convinced by her sister Louise to return to Canada, where she and the children will be taken care of. Richard, with whom Nenna had a brief fling following her fight with Edward, calls Louise and leaves a message for Nenna, saying he’ll probably be attending a series of insurance conferences in Montreal in the spring. The trend of the novel, so focused on the truncated purlieu of the Reach, with its coziness and chockablockness, tricks us into believing that any greater distance, any flight to another territory, would be insurmountable. But of course it isn’t. Fitzgerald’s focus on the particularities and duties of place—as though reality were nothing but practicality, the doing of chores and fulfilling of obligations—blinds us as well.

Not that anything, at the novel’s close, is tied up nicely. Louise, after paraphrasing her conversation with Richard and stumbling over some of the details, remarks that she hadn’t thought it mattered that much. Nenna wistfully replies, “‘I don’t know whether it does or not.’” It’s a final warning that, in Offshore, the only hope we can expect to find is a soft one, threadbare and webby, like an old piece of much-touched silk—it is light, airy, comforting in its way, but just as likely to drift off and away, like a ship out to sea.