The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

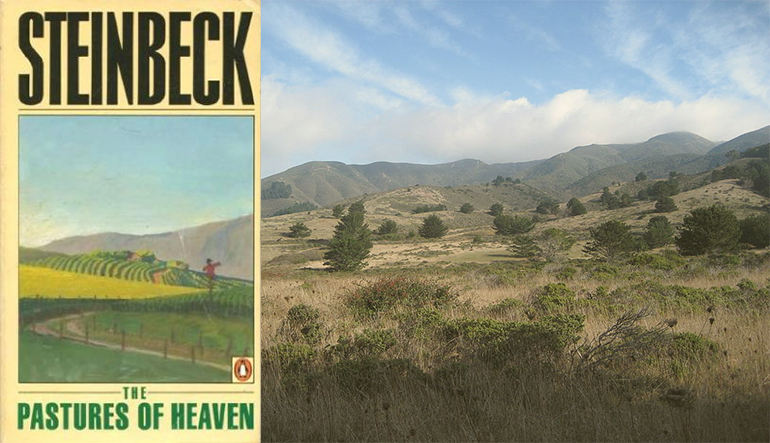

For this first installment, I’m focusing on John Steinbeck as a representative of the Western region in American literature. Known for his simplistically powerful writing style, Steinbeck is perhaps known even more widely for his commitment to his hometown Salinas, California. Most of his writings are set in or around the Salinas Valley (a central California backdrop for his stories on everything from migrant labor to marine biology), and his interests in morality and fate are illustrated by various biblical allusions that reappear throughout his works.

With this in mind, Steinbeck’s first short story cycle, The Pastures of Heaven, is an ideal entry-point, as it is an early example of his interest in diverse characters and events occupying a shared space. Published in 1932, it consists of twelve interconnected stories set in the Corral de Tierra valley in Monterey, California, nicknamed Las Pasturas del Cielo or “The Pastures of Heaven” for its beauty.

The book begins with a Spanish corporal and his horsemen exploring the valley. We learn that “by some regal accident the section came under no great land grant,” so the Pastures of Heaven eventually become the home to twenty families and their twenty farms, rich with fruit and opportunity. This brief first chapter serves as a creation story, of sorts; it details how the Salinas Valley was discovered, the beauty of its verdancy, and begins to describe how the valley became what it is today. This Salinas Valley creation story, Genesis-like in tone and purpose, indicates the start of Steinbeck’s long-standing interest in biblical imagery and the questions regarding morality the Bible promotes. Monterey’s history as the capital of Alta California (read: present-day California), which was shared between Spain and Mexico, makes it a natural setting for Steinbeck to associate with themes of morality and faith, since the use of biblical allegory in both Spanish and Mexican works of art is historically common. With the Salinas Valley as the background for most of his literary offerings, so too is the tension between good and evil. As a result, light and darkness (synonyms for good and evil, as they are widely used) play pivotal roles in the molding of Steinbeck’s fiction.

To this end, the second short story in the cycle begins with the description of one farm in particular, the Battle’s:

The deserted farm was situated not far from the middle of the narrow valley. On both sides it was bounded by the best and most prosperous farms in the Pastures of Heaven. It was a weedy blot between two finely cultivated, contented pieces of land. The people of the valley considered it a place of curious evil, for one horrible event and one impenetrable mystery had taken place there.

Here, Steinbeck uses his setting’s beauty, or lack thereof, as an indication of its level of goodness. The writer’s depiction of the farm as a “weedy blot” suggests an overgrowing darkness at odds with the bright pastures of heaven that surround.

Later, Steinbeck introduces us to the inheritor of the farm, George Battle’s son:

John Battle came home in his caravan to claim the farm. From his mother he had inherited both the epilepsy and the mad knowledge of God. John’s life was devoted to a struggle with devils. From camp meeting to camp meeting he had gone, hurling his hands about, invoking devils and then confounding them, exorcising and flaying incarnate evil. When he arrived at home the devils still claimed attention. The lines of vegetables went to seed, volunteered a few times, and succumbed to the weeds.

The system of land-owning inheritance conveniently demands that Steinbeck keep his stories grounded in the same setting—for if a piece of land continues to stay in a family, the family necessarily continues to stay in the same place. John Battle’s inheritance of his father’s plot, a piece of heaven, is in direct contrast to the darkness he inherits from his mother. This tension, much like chiaroscuro in fine art, brings visual dynamism and shades of morality into the piece. And just as the beginning of chapter two prophesied, the weeds on the Battle farm did indeed serve as indicators of the “curious evil” to come. By situating the next generation in the same valley on the same farm, the reader is able to track the unrelenting grip of darkness quite linearly, making this repeated setting a useful structural tool for the interconnected stories to be followed.

The Pastures of Heaven is a short story cycle, but the shared coordinates of most of John Steinbeck’s stories make his entire bibliography a cycle, really. His characters discover Salinas through migration and accident, they love the valley for its beauty but struggle with its politics; ultimately, these cyclical cautionary tales of California suggest that Steinbeck found and lost most things in his favorite place. For this reason, I argue that redundancy in an author’s career is less of a shortcoming and more an example of how restraints put on literature can inspire some of the most fascinating and challenging work. Though the stories in The Pastures of Heaven are limited in their geography, they are broadened by the way Steinbeck fashions light and darkness into litmus tests for fate.