The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism: Taking the Temperature of Zora Neale Hurston’s Central Florida

The Limits and Freedoms of Literary Regionalism is a monthly series exploring literary regionalism, focusing on different authors who I consider to be “setting-specific writers.” The beauty of these authors’ contributions to literature lies in the fact that they are each able to tell diverse stories, all set against the same environmental backdrop.

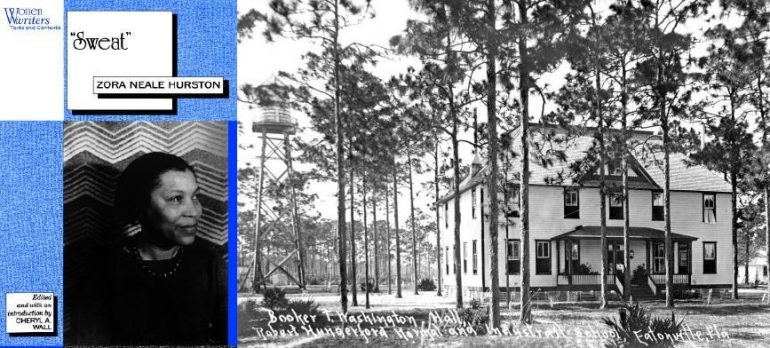

Hailing from one of America’s first all-black incorporated towns, Eatonville, Florida, Zora Neale Hurston grew up with the very people and walking the very roads that would later influence much of her writing. An anthropology major at Barnard (and when there in 1925, the college’s sole black student), Hurston developed an insatiable interest in conducting ethnographic studies. It was this passion for studying people and cultures that led Hurston back to Eatonville—not as a resident, but as a writer.

Central Florida, sticky with humidity and restless with sea breeze, inspires the temperature of Hurston’s fiction and, in turn, the temperament of her characters. In her 1926 short story “Sweat,” Hurston chronicles the marriage of Delia, a washerwoman, and her unemployed, abusive husband Sykes. Married for fifteen years (but their union only unmarred for the first sixty days before the beating began), Delia and Sykes are often at odds over the fact that Delia washes “white folks’ clothes” in their home. Hurston’s Southern setting becomes important when considering the practice of doing laundry. Though sorting clothes by color is standard practice, the act of segregating dark from white becomes more loaded when framed by the waters of the Gulf. And though this division also obliquely suggests the difference between what is soiled and what is clean, there is power in Hurston’s decision to leave the sorting of these colors up to a black woman. Granted, the South allowed women (and black women in particular) little agency, but with an all-black town like Eatonville as the setting, Hurston’s choice feels less like fiction and more like truth. Unlike most of her black contemporaries writing during the Harlem Renaissance, she didn’t have to imagine a world where black people were a powerful majority—for Hurston, that was as standard as washing clothes every week.

Beyond the fact that Sykes dislikes his wife washing the clothes of “white folks,” he is critical of Delia’s tradition of sorting clothes every Sunday too: “Yeah, you just come from de church house on a Sunday night, but heah you is gone to work on them clothes. You ain’t nothing but a hypocrite. One of them amen-corner Christians—sing, whoop, and shout, then come home and wash white folks clothes on the Sabbath.” Ironically, Sykes’ mistreatment of Delia rises to the level of sin: he takes advantage of her abiding fear of snakes by constantly bringing a rattlesnake, or the threat of one, around her. Hurston uses the racial tension in the South as a mirror for the marital tension in Delia and Sykes’ home; much like America, there is much unrest and civil war within its walls. This tension, pulled taut like the clotheslines Delia hangs like commas through the air, reveals itself through Hurston’s treatment of temperature.

Heat has multipurpose utility in this short story: it illustrates Eatonville as an environment of discomfort, made thick with humidity and inequality. Also, heat makes Delia’s sweat two-pronged: beyond the heat of her chosen setting, Hurston uses this natural secretion to remind us that Delia is a working woman whose “sweat is done paid for this house,” without any financial help from her unfaithful husband. And heat is converted into invisible waves when residents of Eatonville gossip about Delia and Sykes’ icy relationship; their words spread like vapor, thin and omnipresent. To explain this communal chatter, Hurston yet again blames the heat, claiming that it “was melting their civic virtue.” With all this in mind, heat becomes Hurston’s instrument for critique. It allows her the latitude to observe the historically tragic Southern labor dynamics, uneven expectations of women and men, and the hellish joy in revenge which, for her characters, is spoken in a language less like English and more like Fahrenheit.

Though Eatonville is never explicitly mentioned as the setting for this story, “Sweat” takes place in a small central Florida town, and is widely accepted to be an early version of the Eatonville in which Hurston set her magnum opus, Their Eyes Were Watching God. The novel’s Janie Crawford feels like a descendant of this short story’s Delia Jones, for they are similarly suffocated by Floridian weather, men, and the red-hot passion that overtakes them. During Delia and Sykes’ climactic fight, Delia admits: “‘Ah hates you, Sykes,’ she said calmly. ‘Ah hates you to de same degree dat Ah useter love yuh.’” This quote, reminiscent of Janie’s final threats to Joe Starks, her abusive second husband in Their Eyes Were Watching God, shows how cold Florida air can become when fear leaves the body like a breath. Hurston’s female protagonists are similar, simply a generation—or a story—apart. They are both products of their environment, but more specifically, examples of the coldness that sets in when the heat becomes too much to bear.

Pushed to her limits as human, woman, wife, Delia becomes exhausted by Sykes’ constant physical and emotional abuse of her, as evidenced by his repeated pranking of her with a rattlesnake. Biblical in its symbolism, Hurston allows the snake to come in between her 20th century Adam and Eve; but in Hurston’s Genesis, Sykes is sprung from Delia’s rib, and his curiosity for something beyond her is ultimately his undoing. So, when Delia finds Sykes’ snake in her laundry basket of clothes, poised to cause her expiration, Hurston’s setting becomes Delia’s strength. The very heat that once caused her to sweat ultimately turns into her salvation. She is ignited by the anger that only comes after years of silence, and one day allows the rattlesnake to bite Sykes in the neck, causing his death, Delia the washerwoman’s hands remaining clean all the while.

With central Florida as her repeated backdrop, Hurston’s characters become her setting’s thunderstorms, wild with unfiltered passion and untapped power, just as unpredictable as the nature that birthed them. Ultimately, the temperature of Hurston’s environment becomes a measurement for more than just heat. Temperature is a way of feeling the passage of time, like how “the sun had burned July to August.” How else can we quantify what it feels like for a people to boil over from the pain and the exhaustion that comes with resisting?