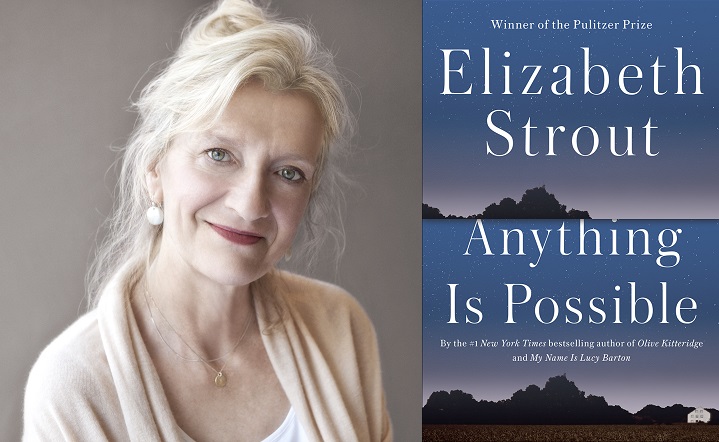

The Linked Stories and Linked Lives of Elizabeth Strout

Small-town America has been at the center of Elizabeth Strout’s work as a novelist. Olive Kitteridge, which won the Pulitzer in 2009, was set in the fictional Crosby, Maine, a town close enough where one person, the book’s titular character, could exert a gravitational pull on every other resident. While 2016’s My Name Is Lucy Barton takes place in New York City, the heart of the story, flashbacks and dialogue between Lucy and her mother, goes back to Lucy’s hometown of Amgash, Illinois. Last month, Strout published Anything Is Possible, a direct follow-up to My Name Is Lucy Barton that, like Olive Kitteridge, uses one central character as an anchor point and builds a web of stories around that character.

In Anything Is Possible’s case, Amgash is as much that central character as Lucy, following in the vein of books like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, Annie Proulx’s Close Range, or John Grisham’s Ford County. Why are rural communities so often the target of linked story collections? It’s not the rule, of course; there’s James Joyce’s Dubliners, Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place, or Stuart Dybek’s I Sailed With Magellan. But I’d bet that proportionately, a higher percentage of linked stories take place in rural spaces compared with traditional novels. Perhaps this is because a small town can be used as a central character in a way that it’s difficult for a city, multifaceted and bursting with change, to be. Over the course of a book, maybe a small town can be known in a way that would be more difficult for a city. Or maybe the limited scope can enhance a book in an important way.

After all, Strout’s books are not just built upon small towns, they’re drawn to themes that a small town heightens, intensifies. When a child is abused in a city and no one does anything, we think of the bystander effect, of systemic failure. When it happens in a small town, it becomes inherently more personal, and thus for a novel, more dramatic. Strout’s characters here are all complicit in one way or another. Some avert their gaze because they think it’s not their place to do anything. Some work hard for selective amnesia. And still others try to make a difference, though their good intentions rarely affect change anywhere. When they do, it’s the small kindnesses that are the most effective: a school janitor who opens up a heated classroom early for Lucy makes all the difference in the world.

My Name Is Lucy Barton follows a more traditional novel structure, but Anything Is Possible returns to the Olive Kitteridge-style linked short stories. People’s lives can be intertwined anywhere, but in a small town it’s taken for granted. It’s a format that Strout seems more comfortable in, resulting in a more natural-feeling narrative arc and overall layered book than Lucy Barton. Lucy, the girl who got away from Amgash and her own family’s extreme poverty, has become a famous writer. Anything elaborates on many of the stories alluded to in Lucy Barton, though everyone has their own versions of what exactly happened. In Anything, Lucy shows up directly in only one story, but she’s in the backdrop of everyone’s thoughts. Most people resent her for her escape, for her reluctance to come back to visit. “I saw Lucy on TV a few years back,” one character says. “Hot shot. She wrote a book or something. Lives in New York. Smork. La-de-dah.”

But small towns, just like literature as a whole, don’t allow for real escapes. Amgash and its residents haunt Lucy: they hide behind her anxiety, her divorce, and her writing. Her family had an awful reputation, not just for being poor but for always smelling bad and hints at darker things, and even in Amgash their house was on the edge of town, casting a metaphorical shadow longer than the literal ones of the huge windmills popping up nearby. But Lucy is not the only one with Amgash-induced trauma. The book travels outside of Amgash in several of its stories, hopping to Chicago and Italy, looking at Amgash’s emigrants and how the town has echoed forward. Strout moves seamlessly between big themes, asking what her characters are willing to do in the name of material comfort or just financial security, love or to hold a marriage together, family or one’s own mental health.

Most importantly, Strout is a powerful storyteller who is not upstaged by the characters on the page. She knows how to cross-reference events between stories without imposing tedium, and which key moments to give the attention of more than one character’s perspective. And like any book with such a large cast of point-of-view characters has to do, she lets them speak sufficiently and passionately enough to give clear distinction between their voices, their troubles. They’re all tragically, thoroughly human, rendered to completion. But in the end, Anything Is Possible isn’t the story of the broken, imperfect, but ultimately good people Amgash connects. It’s not that optimistic.

About Author

Graham Oliver holds an MFA in Creative Writing and an MA in Rhetoric and Composition Texas State University. His work has previously appeared in Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Harvard Educational Review, Full Stop, and elsewhere. You can follow him on Twitter @GrahamMOliver.