The Long Gaze: When Poets Write Memoir

With many contemporary poets publishing (sometimes multiple) memoirs, there’s clearly a desire for these writers to share their worlds in a form other than poetry. Is it as simple as the appealing arc of a compelling narrative? What other issues might come to bear, particularly in our current social landscape, for a poet to share her experience, to say, This is my story—without the poetic slant?

Consider, as examples, recent acclaimed memoirs by Tracy K. Smith and Maggie Nelson, both forces in contemporary poetry. As writers, they are engaged with claiming and expanding the form of memoir, and their efforts have been recognized. Nelson’s book, The Argonauts, won the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award, and Smith’s memoir, Ordinary Light, was shortlisted for the 2015 National Book Award. The memories and experiences that Smith shares, of growing up in a middle-class Black family in Northern California, are filled with warmth and the humor of hindsight for her childhood naïvete—but it is her relationship with her mother, and the loss of her mother to cancer, which frames the book and gives it its power.

In a piece for Lit Hub, Smith described her understanding of the difference between poetry and prose in evoking an event or place:

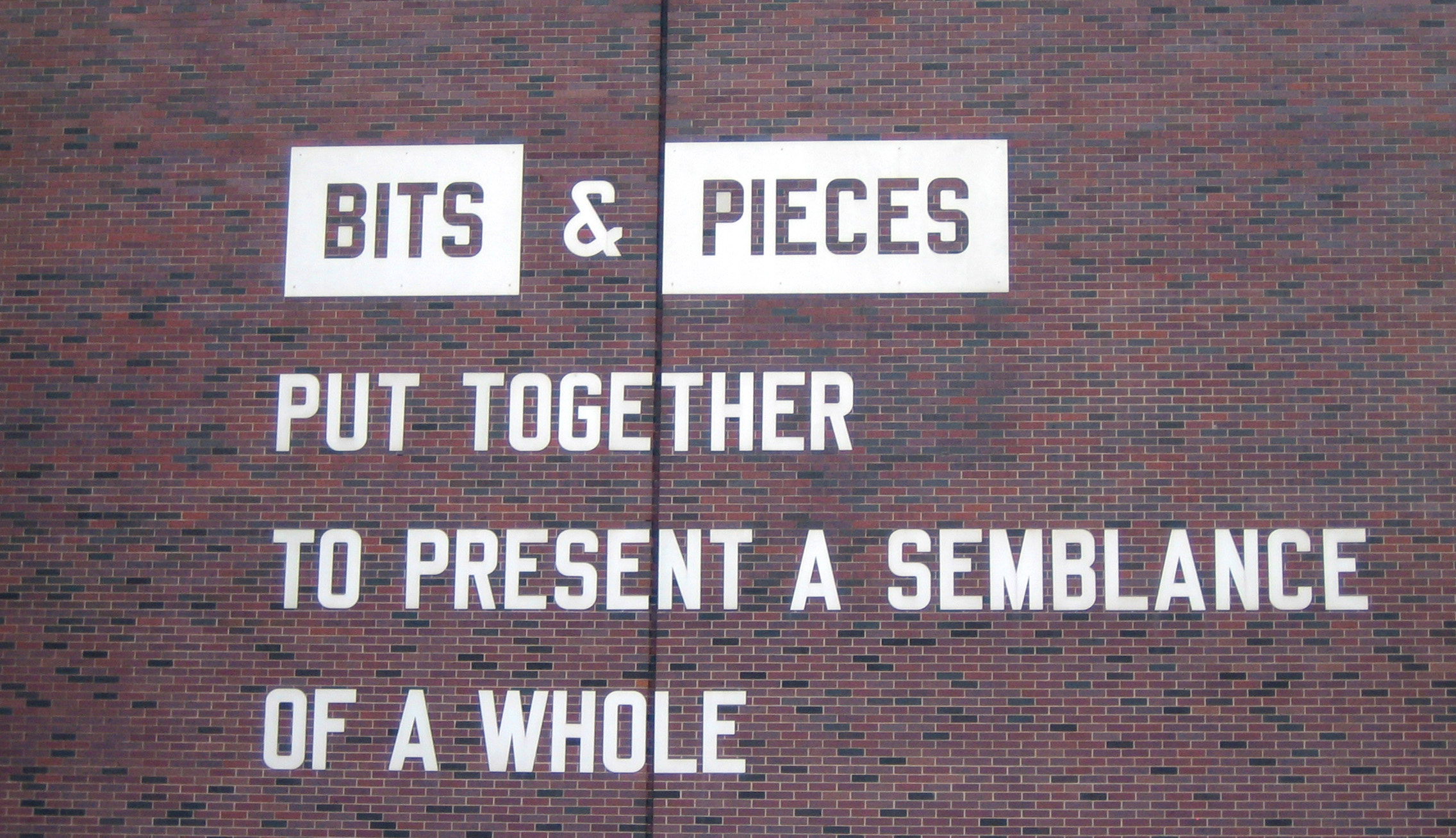

If this is true at least some of the time, perhaps on such occasions it might also be true to characterize poetry as insistent in its vision: departing and returning, picking and choosing, casting and gathering. On those occasions, perhaps it is equally true to describe prose as persistent in its manner of vision. Perhaps it is the long lingering gaze that allows detail and insight to gradually emerge.

For some stories, perhaps, it is necessary to take this approach of persistence and repetition, to record the apparently quotidian details that are often what define an exceptional moment, or relationship, or life. After Smith’s mother’s death, as she sorts through her things, she finds odds-and-ends that hint at so many other details not uncovered: “A notebook dug up from a drawer, in which she had written, Maybe I can publish my cookbook! A paperback, covered in a sheet of Sunday comics … that turned out to be a modest sex manual entitled Nice Girls Do; it struck me as so innocent that I’d felt a wave of almost maternal compassion for her.”

Nelson’s The Argonauts, perhaps predictably referred to as “genre-bending,” enacts the accumulation of detail to tell the story of falling in love, getting married, and having a baby, outside of most assumptions about gender and biology that come with that bundle of statements. As with all her writing, Nelson makes frequent references to literary and cultural theory (the title is a reference to Barthes, as well as to the first time Nelson told her partner she loved him), and these references, often framing her questions about partnership and parenting, accumulate alongside the last-minute pre-Proposition 8 wedding presided over by a Reverend Starbuck and her drag-queen assistant, celebrated by eating ‘chocolate pudding all together in sleeping bags on the porch’ with their young son Iggy.

As with Smith’s memoir, much of Nelson’s story is one of navigating and chronicling happiness, the joys of a life less familiar—or one we as readers see less often in media, in which white heterosexuality is still firmly entrenched, or in memoir, in which trauma is the rule, rather than the exception. Even though Ordinary Light can be read as an elegy in prose, it is a story of a young Black woman’s loving relationship with her mother, and its daily, what we might be tempted to be call small, moments.

In 2005, Smith wrote an essay on the poet Lorca’s concept of duende (which was also the title of her second book of poems). Duende has elements of mystery, of danger, of loneliness. For Smith, poets writing from a place of duende inhabit a “world where madness and abandon often trump reason, and where skill is only useful to the extent that it adds courage and agility to your intuition.” The vast abandon of space that her speaker traverses in her grief in Life on Mars exhibits this duende. In Ordinary Light, there is no speaker, there is Tracy K. Smith, at her mother’s bedside, in her final moments. In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson must navigate her partner’s anxiety at his portrayal in the memoir, the idea that her happiness is potentially at stake. We’re lucky, as readers, that they take the risk; maybe, too, that they have a relationship in which she can share the vulnerability of that conversation.

It’s easy to tell ourselves right now that the world is made up of madness and abandon. Perhaps, then, this is a moment for our most gifted writers to offer us something else. Not an abandonment of poetry, but a reminder of the worlds that are open to us, the alternative narratives, the small joys, the long gazes.