The Many Disappearances in Run Me to Earth

In 1969, the three Lao protagonists of Paul Yoon’s new novel Run Me to Earth are around seventeen years old. In 1969, my parents were only twelve. They would not escape the civil war in Laos until five years later, under the cover of night, each fleeing a different region of the country. In a rare moment of vulnerability, long after, my mother would tell me: “I looked at my father, who was standing outside our house. He was staring at me with such a look on his face. I think he knew I was going to disappear. That’s what happened back then. You’d wake up one morning, and people would no longer be there.”

My mother, a woman who does not easily reveal her feelings, still cries when she talks about the night when she chose to cross the Mekong River into Thailand. She did not see her father again for over two decades.

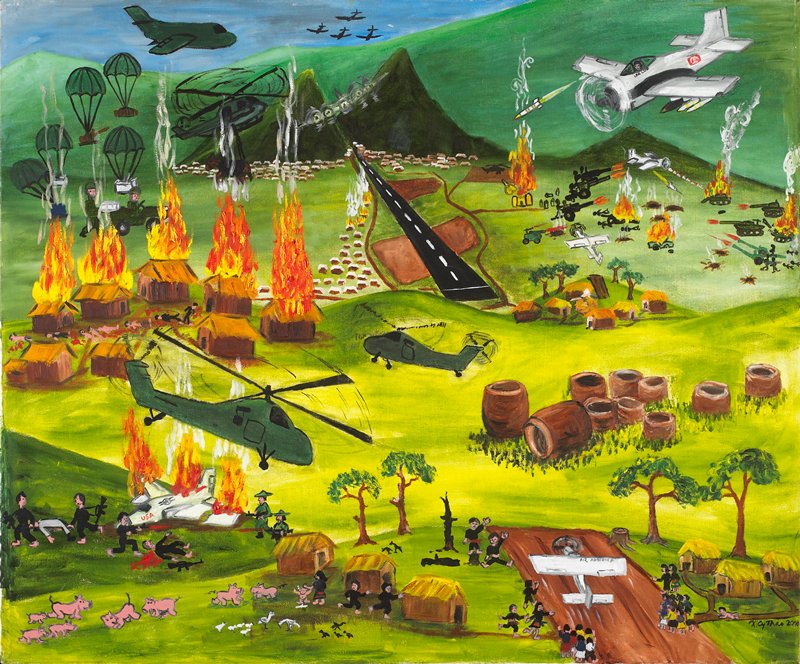

For Lao refugees, every retelling of our history is intensely personal. Largely ignored by writers and filmmakers, we have taken it upon ourselves to document everything that has happened to us. In recent years, our efforts in the margins have started to gain momentum in the mainstream media. Back in the early aughts, barely out of my teens, I had written an essay for the Lao Literary Project SatJaDham, a journal the size of a chapbook that felt like the most wondrous anomaly at the time, which I had only learned about through word of mouth. Now, the Lao American Writers Summit, a national collective of Lao diasporic writers of all genres, boasts over four hundred members. In January, Rita Phetmixay—a social worker, educator, and documentarian—wrapped up the first season of Healing Out Lao’d, a podcast that centers storytelling and mental health via an intersectional approach. At the Minneapolis Museum of Art, a series of fifty drawings depicting the Vietnam War by Laos-born Hmong American Cy Thao were on display this winter, rendered in a naïve style inspired by both the tapestries of Hmong women and Picasso’s famous Guernica. Activist Bobbie Oudinarath, based in California, successfully pushed Bill AB 1393 through his state legislature to include Lao American curriculum in school textbooks.

We wanted people to learn about us—we wanted our stories to be told. And yet, when it was revealed that Yoon’s latest novel, released late last month, would be about the events surrounding our escape, the Lao-American community reacted with mixed feelings. For some, seeing our history discussed at all on national platforms felt like validation. But for many, it felt as if a stranger had assumed our voice. It was like watching the movie of our lives, with our lines dubbed over.

To give context to these mixed feelings, it is crucial to understand that Yoon’s novel arrives at a complicated time for us. This year marks the forty-fifth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, but Lao refugees who came here as children are now being threatened by the Trump administration with deportation. History is sadly not history enough. We are still addressing the consequences of our displacement, often with minimal visibility in the public discourse. To write about our past from a position of visibility and not address the current struggles of the diaspora, then, is like treating our trauma as a museum artefact rather than a living entity. As a compulsive history reader, I value a museum’s mission to educate, but this kind of trauma enshrinement turns us, Lao people, into a topic of dissertation rather than an interlocutor. Artefacts can be removed after a war has ended, but, as Run Me to Earth illustrates so elegantly, trauma cannot. Despite this, there is life and joy to be found within it, and beyond it.

In the six time-jumping stories that form the novel, Yoon traces the lives of three teenagers in Laos, which is in the midst of being bombed by the Americans in their campaign to stop the movement of supplies traveling underground along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Alisak, Prany, and Noi must navigate a land that has become riddled with unexploded ordnance, a land fought over by the communist Pathet Lao and the US-backed Royal Lao government. When the latter group hires the teenagers as couriers for one of their makeshift hospitals, the children accept not out of political belief, but because it is the first time in a long time that adults have spoken kindly to them.

At the hospital, the trio comes under the leadership and the protection of Vang, a gentle doctor who plays the piano and teaches them French in the quiet moments that sometimes miraculously settle over the ward. Vang (whose name recalls that of Vang Pao, a real major general in the Royal Lao Army and Hmong American community leader), knowing that more American planes will be attacking the area soon, manages to secure their evacuation by helicopters from the Lao government, but the adolescents become separated as they ride their motorbikes on their way. A cluster bomb explodes. From that point on, we, the readers, become witnesses to the many disappearances that punctuate war-torn lives: of neighbors, memories, motorcycles, colonizers, baskets, friends, body parts, names. Some of these disappearances, however, like new continents emerging from volcanic eruptions, lay the ground for Yoon’s characters’ destinies.

The first scene of the book, told from Alisak’s perspective, opens in the hospital at night. The teenagers are playing a game in which each of them imagines where they would rather be instead, “but no one ever says home.” They are orphans who have only each other. Alisak is intelligent, thoughtful, and internalizes everything, whereas Prany is the risk-taker, generous, and brave—more prone to follow his impulses. Prany’s sister, Noi, is a year younger than the others and still has the soft glow of joy despite their situation. Like her brother, she has a streak of unflinching bravery. The three of them attempt to provide as much comfort as they can to the patients who are too injured to be evacuated. They keep the curtains open for those who want to look at the Plain of Jars, an archeological site where mysterious stone jars the size of cars are scattered throughout the Xiangkhoang plateau. Their origin, shrouded in myth, is an unsolvable riddle.

As far back as they could recall, Alisak, Prany and Noi had heard so many stories of the megalithic stone jars they weren’t sure which one was true: whether they were intended to collect rainwater for travelers; whether they were used to make wine for warriors who would return from great battles. It was also said that the jars once belonged to giants who roamed these hills. And others thought the jars had nothing to do with this earth at all and that in some future time someone or something would come back for them.

The jars, by their presence, conjure up the ghosts of those who have carved them and are no longer there to explain their purpose. If the ones who made such imposing vessels can simply disappear, be they warriors or giants, then the jars are an outsized reminder that anyone can disappear senselessly. The jars, having sat undisturbed for thousands of years, are being destroyed and replaced by another kind of artefact—cluster bombs dropped by the American government, an ally of Laos whose self-interested interventionism causes more damage than good. Saturated with death traps, the Plain becomes a geographic heart of violence, a place where the silence that follows every detonation is a new absence to be mourned, a new illness to carry.

Knowing they cannot stay there much longer, the teenagers wonder where they will be evacuated to, either France or Thailand. France intrigues them, not only because Vang speaks French, but because the hospital has been operating from a grand colonial house that used to belong to a French national, a man nicknamed the Tobacco Captain who once had hired Noi as a server for one of his parties. No one knows where the Captain, one of the last French expatriates to remain in the former colony, has gone. His art collection remains in the building, as does his collection of vintage motorcycles that the teenagers use for their supply runs between the makeshift hospitals. Though he is nowhere to be found, the Captain’s disappearance is the promise of a new life for the three teenagers. The man’s estranged brother, a country doctor saddened by the inexplicable loss of his sibling, offers to sponsor Alisak, Prany, and Noi into France—they are the last connections to his family, no matter how tenuous. If the Plain of Jars is the force that pushes them away, the void left by the Captain’s disappearance is the force that pulls them ever closer to their fates.

But these forces come to a clash in the brutal disorder of war. As Alisak, Prany, and Noi speed their motorbikes towards the helicopter that is about to land a short distance away, they are separated in a blur of decisions that they make in the heat of the moment. Amidst the explosions and the havoc of soldiers trying to evacuate people before the enemy finds out, the teenagers vanish from each other’s lives. Alisak is sent to France, Prany is captured alongside Vang by the Pathet Lao, and Noi’s path is left ambiguous until the penultimate chapter of the book. Though the six stories jump through time, the memories of their friendship collapse into each other, forming a poignant and devastating picture of children who had to grow up too fast, and yet remained children, their hearts undone by a grief they are unable to articulate. Alisak, finding himself in the house of the French country doctor, keeps leaving at night and falling asleep outside. He assists the doctor for a time, but eventually leaves without explanation. Disappearing, which had always been something outside of his control, is now something Alisak does consciously, as if to find the end of it, to see what lies on the other side.

For Prany, who is captured and sent to reeducation camp with Vang, it is the concept of time that has disappeared. He is tortured by the Pathet Lao interrogators for years. In one brutal session, he loses the use of one of his hands, and yet it is the loss of time from which he suffers the most. When the Pathet Lao finally sets them free, after having successfully “re-educated” them, the first thing Prany asks Vang is what day it is, needing to hear someone confirm that his life has regained some kind of structure outside of the fog of violence he has known. Time, when dismantled, makes cruelty last a lifetime, and in his need for vengeance Prany follows his worst instincts. Like for Alisak, however, the warmth of the trio’s connection cannot be forgotten and it is the memory of love that drives Prany’s last act. After having committed an unconscionable deed, he chooses to sacrifice his future in order to save the lives of others.

Our knowledge of Noi’s fate does not go past 1969, until another character mentions her. Like many stories borne of war, there are gaps that will never be filled, threads that are abandoned along the way, only to be picked up later, sometimes unsatisfactorily. Her disappearance is perhaps the one that lingers the most delicately over the readers, as the lives of other characters move forward and we feel the ache of no longer seeing the girl who meant so much to her brother and her friend. As Alisak’s voice closes the last chapter, his thoughts wander to someone else, a woman who has escaped Laos as well and who had come to deliver him a piece of paper from Prany. Prany, whose last words to her had been to never forget the trio’s names. But remembering their names does not replace what the readers or any of the characters wish they knew. What was it all for? What was the meaning of it? Could they have changed anything? Like the Plain of Jars, over time, the names of people also become unsolvable riddles. It is something that children of refugees, like me, have observed intimately in our lives: our parents, suddenly lost in thought, a long forgotten name appearing on their lips only to disappear again without an explanation.

This is the strength of Yoon’s novel. He documents the silent trauma of war survivors with exquisite beauty, finely detailing the movements of the heart in the grip of violence, both interior and exterior. Run Me to Earth is the sort of narrative that is needed in our efforts to document the consequences of war, a necessary record of unspoken loss and unspoken mourning. Perhaps this is why the most glaring disappearance of the book stood out to me: the disappearance of cadence.

When you have no written record of your past, as most Lao people do not, speech becomes your only documentation. And when you do not have the words to explain your trauma, cadence becomes your only documentation. If you picture yourself running for your life, first imagine how fast you would run, then how breathless you would become. Imagine hearing a noise and being spurred into action again, and then staying quiet for a moment before darting off. The cadence of Lao speech is a bit like that. Reactive, halting, alternating between nimble and heavy. Weighed down by the trauma of an entire nation yet spurred by the imperative to live another day. In the short story “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” published in the New Yorker this month, Cambodian American writer Anthony Veasna So makes beautiful and accurate use of this particular rhythm. Though the protagonists of So’s story are Cambodian and Yoon’s are Lao, the two communities share much in common, including a rich and varied oral tradition. And this tradition affects our speech. The characters in Run Me to Earth were Lao—they just did not sound Lao to my Lao ears. Their dialogue, devoid of our cultural idiosyncrasies, was polished and unfamiliar. It is not merely an issue of style—it is an issue of voice. What makes these characters Lao? What makes them different from the kids in Darfur or Damascus? There is a thin, but tangible line between wanting to make their pain universal and making it interchangeable. In such a stunning book about loss, the disappearance of our unique relationship to Lao language feels like a punch in the gut. Did you know that Lao people do not conjugate verbs at all? Think for a moment about how that shapes the way Lao people think and speak of time.

Time has always been on Lao people’s side. We know how to bide it, we know how to laugh through it. The Lao sense of humor is spectacular, if you ask me, not dissimilar from the humor found in the great Russian novels, the kind of humor that understands the power of resistance in the face of bloodshed and political upheavals. In the struggle we face against threats of deportation, books like Run Me to Earth can be useful. Though we may carry mixed and not-so-mixed feelings about Paul Yoon’s decision to write about us, it is nonetheless important for people outside of the Lao community to help contribute to a historical narrative that has been criminally neglected—because dropping more than 270 million bombs over a small country is criminal. Deporting the refugees who came here as children is criminal. As more Lao writers enter the literary world, our voices will recalibrate a small corner of English language, infusing it with our particular sounds, turns of phrase, and humor. In an essay about Kent Monkman’s exhibition on Native Resistance currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Nick Estes, an assistant professor in American Studies at the University of New Mexico, writes that Monkman “forces each one of us to confront the real, while demanding we undo the unreal. The act washes over us likes waves of history, ebbing and flowing, oscillating between love and rage.” At the end of the day, the novel is not real, but we are. Speak to us.

Image, #22, by Cy Thao