The Multiple Consciousnesses of Exile

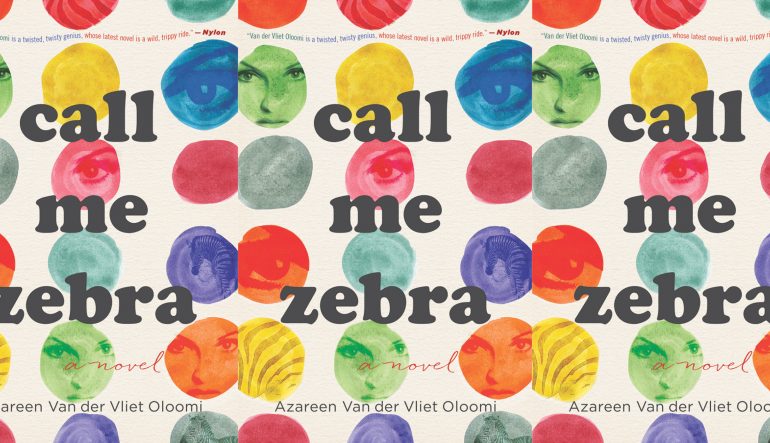

In the recently announced PEN/Faulkner award finalist Call Me Zebra, Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi follows a young protagonist on her journey through exile from Iran to Spain, the United States, and back again. Zebra—the last in the line of the Hosseinis—follows her family motto to “guard our lives with our deaths,” along with their charge to trust nothing but literature, with a fervid passion that borders on the absurd. Intelligent beyond measure and equipped with an encyclopedic knowledge of literatures from multiple languages and traditions, Zebra establishes early on that she will not play by the social codes of the West by refusing a traditional higher education despite multiple scholarship offers. In an initial display of satire’s power as a tool of critique, Zebra states that American universities only want to exploit her diversity for the sake of their domestic students—an extension of the foreign policy of the United States of America (or as she calls it, the Unanimous Station of Apathy). Instead, she persuades a communist Chilean exile to serve as her mentor in her quest to write a manifesto on literature. As she digs deeper into her mind’s crevices, she discovers that her trajectory of exile has produced multiple selves: in each new geographic space her exile brought her to and later wrenched her from, a new version of herself entered the world.

When analyzed next to W.E.B. DuBois’s concept of double consciousness—the state of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity”—Van der Vliet Oloomi’s concept of multiple selves strikes uncannily similar chords. DuBois explains double consciousness as a “twoness”—in his case, as both an American citizen and as a black person. Due to the hierarchy created between these two identities by an oppressive, white supremacist society, those experiencing double consciousness internalize the idea that they are both American yet subordinated, and it is within this dichotomy that they form their social self-consciousness. This group must learn to navigate a system that functions on the approval of the American citizens who do not share their subordinated identity: those who are white. In similar social frameworks, Frantz Fanon has written about colonized peoples “stumbling over the need to assume two nationalities, two determinations,” and other scholars, such as Edward Said and Hatem Bazian, have linked descriptions of double consciousness with the similar conditions of being an “other.”

While DuBois’s double consciousness is an experience particular to black people in America, the concept of forming an identity within a society born from and continually profiting off of white, Western supremacy provides a useful introduction to discussing the pain of exile and otherness. This double—or often multiple—consciousness stems not only from racial profiling, gaslighting, and negative perceptions, but also from the rampant well-intentioned statements, pity, and unaware tokenization that divulge the onlooker’s ignorance of an exile’s background or state of being. In other words, a hotbed of both positive and negative intentions consistently puts the burden of understanding on the outsider, which leads in turn to resentment, social exhaustion, and internalized oppression. Pairing perspicacious absurdity with a main character who confronts her multiple selves—or consciousnesses—Van der Vliet Oloomi unearths spectacularly astute and poignant truths of life as “other” in the global North.

Resembling literal embodiments of a fractured consciousness, each of Zebra’s multiple selves stems from a different location in which she experienced the effects of exile. When her study of literature leads her to realize that it has evolved by a process of distorted duplication, that the world and books are simply infinite reflections of each other, she determines that the world and literature are one. She uses this realization to turn the mechanism of her pain—her fractured consciousness—back onto itself. By revisiting the origin places of each of her multiple selves and melding them with the many selves she picks up from her study of literature, Zebra predicts that she “would give birth to literary duplicates and distribute between them the pain of [her] erasure.” She thus sets out to retrace the steps of her exile and directly confront her multiple consciousness. Along the way, Van der Vliet Oloomi paints a striking picture of what it is like to live in exile, to be cast as an outsider in all spaces where life is possible.

Zebra’s first traveling project, the Grand Tour of Exile, begins as she embarks from New York to Spain to retrace the steps of her exile. During this time, we learn about Zebra’s devised Pyramid of Exile: at the top are exiles in denial, couched in privilege or otherwise partially “assimilated” into their respective new societies; in the middle are exiles such as Zebra, who find themselves alone and despondent, but with social and geographical mobility at their fingertips; at the bottom are refugees with extremely limited resources and options. In Zebra’s conception, those at the top and middle of the pyramid constantly stomp on the heads of those directly below them, feeding the Pyramid with “fresh blood” and perpetuating the cycle of exploitation for personal gain that the West thrives on, though none of those in the Pyramid have been fully accepted in their new Western contexts. With this bloody, near farcical diagram, Van der Vliet Oloomi reveals the chilling reality that is often the most viable avenue forward for those cast away by the dominant social classes: upholding the very system that prohibits their own social mobility, keeping others below them so that they can move up in the cyclical, violent Pyramid.

Throughout her travels, Zebra also turns the “amused contempt and pity” DuBois identified as the lens through which the other is viewed onto the onlookers themselves. She starts conversations based on extremely specific interpretations of literature likely unread by the masses with random people around her, such as a man across the aisle from her in a plane, an unsuspecting neighborhood grocer, and a young tourist woman. She speaks to them as if they have been inside her head for months without giving them any indication of what her cryptic statements could possibly mean or even relate to, casting these people into the position of the outsider to her world. She often accomplishes this with humor and almost always with contempt and pity for those she deems “hopeless,” “primitive,” or “unexceptional.” By turning the gaze of the onlooker back onto itself, Zebra finds small pockets of amusement in talking with the people for whose benefit she notes she has been “ghettoed in the Pyramid of Exile.”

Later on, as Zebra seeks revenge on her companion, Ludo Bembo, for meddling with her notebook and her plans, she finds herself discussing her goals with the trees outside his apartment. Through this seemingly absurd conversation, Zebra gains clarity regarding her pain and how she can truly challenge it. She learns that she will always “continue to reproduce [herself], thereby preserving the discontinuity of exile and confronting the self-satisfied ignorance of the unexiled,” a prognosis of eternal suffering. She also discovers, however, that she can use her multiple consciousnesses to act in direct opposition to this painful effect: she can stitch her multiple selves to the geographic places that produced them by transcribing “the spooling lines of the literature of exile” written by those exiled in these same places before her. In doing so, Zebra will “embed [herself] once again in the fabric of tradition.” Forging a geographic and mental camaraderie with the literary past, Zebra inserts her exiled consciousnesses into the physical space of exile’s many literatures, creating a bond with the tradition of those who have been similarly torn and expelled from their cultures, building a new tradition with which to belong.

While satire and humor provide Van der Vliet Oloomi a sharp avenue to uncovering social critique, many characters in the book balk at Zebra’s own absurdities. Accusations against Zebra’s incongruities with Western social codes are common in Call Me Zebra, such as when Ludo Bembo complains that she is “ignoring reality” and that her thoughts and values are purely “absurdity.” In response, Zebra hurls retorts that slice through the bias of these accusations. She asks Ludo Bembo, “Whose reality am I ignoring? Because I’m sweating bullets trying to untangle the great knot of my past,” revealing that what many call reality—often a term used in this context to imply that the social machinations of capitalism such as work and status are more “real” than social justice—does not account for the very real experiences of those who have not assimilated. Later on, she says, “There is nothing absurd about any of this. I am simply living by the laws that have governed my life.” Here, she refers not only to the values and family commandments which her father and ancestors instilled in her, but also to the truly preposterous conventions governing exile and the minutiae of navigating social spheres as an outsider.

Much like Zebra’s way of living seems ridiculous to the assimilated or unexiled citizens around her, Zebra notes that the opposite is true for her: “The codes those who are less burdened with history live by will forever be illegible to me.” Earlier in the book, however, she notes that despite the fact that she does not understand these codes, she has taken great strides to fit in with multiple societies: she “[speaks] so many languages and yet [she is] understood by no one. . . companionless despite [her] ability to operate a plurality of systems.” Through these and other conflicts between Zebra’s and the West’s norms, Van der Vliet Oloomi exhibits the double standard with which the West regulates what is commonly understood. The onus is always on the outsider to interpret, adjust, and live by the conventions of those more privileged, perpetuating the white, Western supremacist social hierarchy that created DuBois’s double consciousness. In following Zebra’s journey to confront the embodiment of exile’s fractured consciousness and her refusal to dissolve into Western social codes, Van der Vliet Oloomi’s humor and literary power bring a fresh, clear, and unapologetic voice to the experience of living as an other in the global North while simultaneously shedding light on exile’s true absurdity: that society remains apathetic toward the exiled.