Why Canada’s First Nations Men Might Fight for Colonists

October offers two reasons to honor indigenous literature. In the States, this month brings Columbus Day, often called Native Americans’ Day or Indigenous People’s Day. October is also Canada’s Thanksgiving. So as a means of honoring both, consider First Nations author Joseph Boyden’s debut novel, Three Day Road.

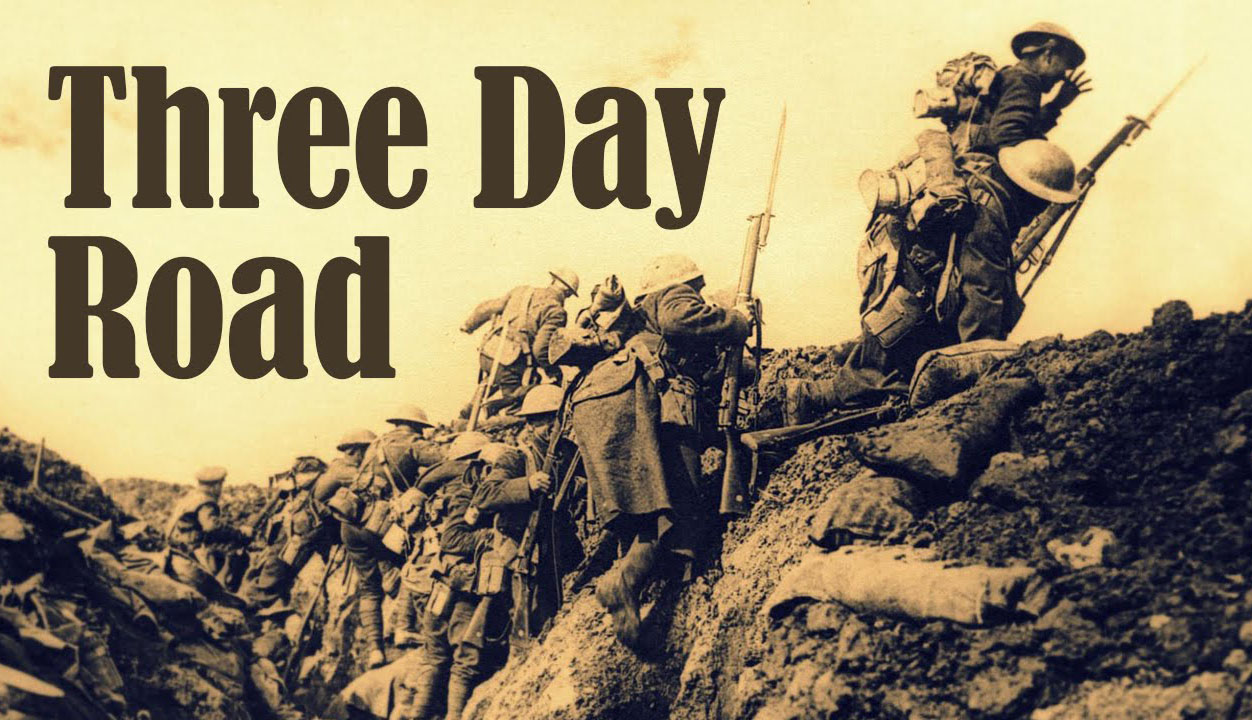

Three Day Road, a historical fiction story about two Cree Natives, Xavier and Elijah, who volunteer to enter WWI fighting for Canada is tough to put down. Part Métis, Boyden lets us inside the world of the First Nations people enough to see how well their skills as hunters served them (and the Allied forces) well.

The book is inspired by the real life story of Francis “Peggy” Pegahmagabow, a First Nations member who served as a sniper and scout in the Great War and later became a respected chief of the Ojibwe (now Wasauksing) First Nation (Parry Island) tribe. Also influencing the book is the story of Boyden’s father, the highest-decorated medical officer of World War II.

Boyden’s story stops just as his First Nations protagonist, Xavier Bird, returns to Canada. He has lost a leg and has been shot in the arm. He’s hooked on morphine, from which his aunt Niska helps him detox as they travel in a canoe for three days into the forest, returning him to his native, natural roots. The story is told from Niska’s and Xavier’s perspectives, granting readers insight into the indigenous experience at war— and at home.

Boyden, who is part native, doesn’t infringe upon the repute of Peggy but parallels it. Peggy makes a cameo appearance as a sniper emulated by Elijah, Xavier’s pal and fellow sniper. Elijah sees Peggy as mysterious, an exceptional competitor provoking him on to higher and higher kill counts.

This is a tale of survival and courage. Boyden creates a gripping tension between the war in the French countryside and the quiet yet also deadly Canadian countryside. He takes us through a range of side of emotions. His characters forge relationships based on deep respect, admiration, and love, whether it’s between war buddies and their leaders or between Natives. Those relations can change dramatically when the survival instinct kicks in, and in that chasm between love and survival readers witness the human condition. It’s this universality that Boyden captures with fine literary skill.

Boyden does not offer a reason as to why these First Nations young men should sign up for the war effort at all. Instead through these two men he’s able to show at fictionleast perspectives on how they felt about fighting for former colonists, which perhaps leads the reader to answer for herself. Though one could guess that Elijah wants to experience the world and gain glory. Those demons manifest wincingly graphically.

“He goes to meet (the Frenchmen who told him to scalp his victims) and show his skill as a hunter. All he carries now in his pack are the trophies of the dead,” Boyden writes about Elijah. Those trophies of countless scalps, however, will prove to be his downfall. They will, in fact, cause an arresting, chilling ending that’s skillfully woven together via multiple subplots as Elijah becomes addicted to morphine and the thrill of danger, and as his kills of German soldiers (and others) become more gruesome.

“I will help pull him from the war madness that swallowed him whole,” Xavier thinks as the stresses of war fray the brotherly connection between these two Natives. “I remember him learning to love killing rather than simply killing to survive.”

Elijah is not all villain. He does save Xavier’s life. When the latter, a shy and quiet one, finds out that it was Elijah who set him up with a woman who (likely) took his virginity, Xavier becomes hurt and irate. In an attempt to find out if the woman really felt anything for him he deserts the camp for a day or two. A lieutenant wants to bring him up on charges of desertion when he’s caught returning to camp. Elijah lies to the lieutenant, making up excuses that save Xavier from the firing squad.

“You are a lucky bastard. You are lucky that I am such a good friend,” Elijah says. “I knew that a woman would be good for you but that you would never visit a whore, and so I did this for you to help you, not to hurt you.”

Three Day Road is full of powerful scenes, scenes that make us contemplate our own limitations and capabilities, the tribes we belong to, and our broken connections with people and nature. Read it to learn more about First Nations people. Read it to learn more about colonists. Read it to learn more about yourself.