Why Culture Cops Are Bad for Writers of Color

The biggest fear of most professional writers I know is drawing the ire of the internet. This is especially true among writers of color I know. And as the article that appeared in Vulture last week, “The Toxic Drama on YA Twitter,” showed, our literary communities are no exception to the dark allures of destructive, righteous outrage. While the article focuses in on diversity-in-publishing movement and the way that message has been co-opted and perverted by a few to tar-and-feather one white author whose work interrogates race, I think it’s worth discussing how that same brand of righteous outrage can work against writers of color too and especially women writers of color.

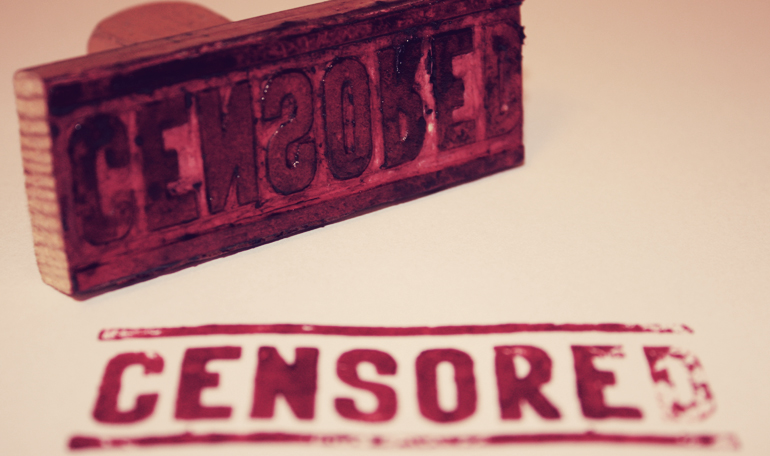

Personally, it’s a very real fear in 2017, the culture cops. And though the Patti Smith part of my mind is like, I don’t give a f*ck what you think, I do worry about my own work (or career) being lost to the loudness of outrage, which I think—worse than being destructive—is as dangerous as outright censorship itself.

After all, righteousness’s job is to cut the legs out from anything deemed offensive (politically correct or not). And historically, destructive righteousness has been used as a substitute for critical thought, a way to bully enemies and their ideas into submission without having to actually critically engage them.

Constructive righteous outrage is one thing (publicly shaming Bill Cosby for sexual assault was a constructive thing, an arguably good thing that directly confronted rape culture). But, to be clear, destructive righteousness is the thing I’m talking about here. Destructive righteousness is the place where stuff like McCarthyism comes from (Are you as American as you should be?). Or phrases like, I was just following orders, sir. Policing. Power play. Billy clubbing. Destructive outrage.

That destructive righteousness (that need to censor) has always affected literatures from people of color by self-proclaimed advocates of diversity. A colleague of mine, Dr. Paul Kintzele, pointed me toward the example of Trinidadian writer CLR James’s 1939 novel, Minty Alley, in which it’s written in the forward how upon publication of James’s work, “Letters protesting against the obscenities . . . pour[ed] into the [Trinidadian] Guardian office during the past week. One is from a Boy Scout who says: its disagreeable implications cast unwarrantable aspersions.” In this same forward, the author riffs on how this reaction echoed the experiences of earlier Harlem Renaissance writers who “shocked those Negro American Conservatives anxious to be acceptable to White Americans.”

Today, we see that same outrage online (via Goodreads, Twitter, Amazon reviews, blogs, etc.) in response to works from writers like Roxane Gay, Erika L. Sanchez, and Lilliam Rivera, among others. Women of color who have given the world nuanced, flawed, and interesting characters but who have received flak in response to their work that sometimes paints their cultures, communities, protagonists, or themselves in a less than favorable light.

While contemporary white authors are allowed to freely write complex, misanthropic characters into their work without incident, writers of color consistently confront culture cops who take issue with the portrayal of those characters in a diverse context. But what is a story without evolution of character anyway? Who is a character, really, without flaws? What’s the point of writing if not to tell some basic truth?

Repping one’s culture in a less than positive light is typically what sets these people off. And this is a kind of policing that consistently falls on writers of color but especially women writers of color who dare to write characters that give nuance to a thing that affects the women and girls within that community or, god forbid, expound upon an idea that relates to another community.

Outside of the realm of writing, but within the realm of writers, the most famous recent example is probably Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s public shaming after a Channel 4 interview in which she said the lived experiences of transgender women aren’t the same lived experiences as “real women.” Problematic for sure. But also a fact that Adichie goes on to qualify in the next statement by talking about the violence of gender as a sociological construct (imposed on one from birth) as opposed to a purely biological one. And even though personally I find that bit about “trans women are trans women” problematic—her use of “real” as a descriptor of women implies there is a correct way to be a woman—I also have to take into factor the larger context of the interview (which even informs that bit) and stems directly from her views on how “feminism and femininity are not mutually exclusive.” A novel idea that Adichie uses to tear down the “slut/serious person” binary problem she presents earlier, but ultimately an idea that was completely drowned out by righteous outrage (justified or not) about her later comment.

Google any article about that incredible interview and it’s mostly been summarized as “Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie Transphobic.” The power of its ideas have been completely stripped from it. Which I’m sure felt good to some people but ultimately I wonder—did they listen to the rest of the interview? Like, did they get anything from it outside of rage?

I think this is something we, as writers and critics and ragey internet people, have to be cognizant of: that even when, as a culture, we police something with the best intentions, we strip away the entire message. We strip it of humanity. We billy club it to a thing we can hate. And in the process, we start policing ourselves by closing off our minds from those ideas. When we replace critical thought with our righteous outrage, we censor our thought patterns. We reinforce our echo chambers. We disengage. We stymie our growth.

When we’re like, “Got that guy. Look at him now. Hey everybody, he’s angry on Twitter. I did that,” we make ourselves dumber, not smarter. Because literally we opt out of having to critically engage with the entirety of those ideas. And going back to the way this policing directly affects writers of color, we have to think about how it does something worse: how it cuts the legs out from under the very writing that makes our world richer in an era that sorely needs good, complex characters from writers of color now more than ever.

What’s always struck me as ironic about culture cops is that they’re never around when you actually need them. Like, there are actual racists, bigots, transphobes, homophobes, etc. in the world doing more evil than someone like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, yet she’s the one that somehow entices the complete wrath of the internet. But why do they go to her? I think because it’s easy. For some people, it’s probably fun—you get some clicks, you get some retweets, you can see her respond via Facebook. I’m sure some people were satisfied they had to make her do that.

But more darkly, I think it’s because the world is uncomfortable with someone like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a prize-winning public intellectual, a groundbreaking black woman writer at the top of her game. This is not to say what she said was right or just, but you can’t deny that the backlash was the vehicle through which the world tried to bring her down a peg.

And this is the danger of destructive righteous outrage. We have to ask ourselves: in which way could this outrage be a part of a larger and longer tradition of systematic oppression? And is it truly righteous? I think if we’re honest with ourselves, if we challenge ourselves to critically engage with our anxieties (as well as the ideas), we’d be surprised.