A Carrier Bag Theory of Revolution

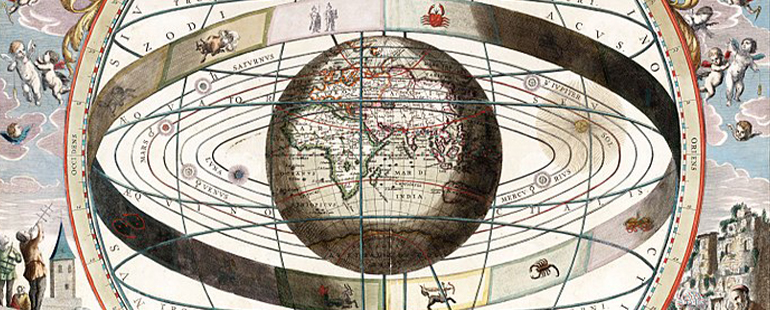

When Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” was first published in the 1988 collection Women of Vision: Essays by Women Writing Science Fiction, edited by Denise Dupont, nobody knew how conflicts brewing at the time were going to turn out. It was unthinkable that the Berlin Wall would soon fall, that the Cold War would effectively end without widespread nuclear annihilation, or that Nelson Mandela would be released from prison after twenty seven years and go on to become the President of South Africa. The increasingly extreme scale of the world’s simultaneous interconnectedness and fragility was just beginning to show. We never know what the world will look like the next time it swings around its elliptical path. In this sense, then, all times are “uncertain times,” but the phrase has, of course, acquired extra weight this year.

Maybe the only certainty is revolution: the Earth continues to follow its path around the Sun. That perpetual state of revolving is not what most people first imagine when they hear the words “revolution” or “movement.” But come what may, our home planet—a container for so many brief and precarious lives, so many antique and seemingly unyielding structures of power—continues to revolve. About two months ago, Arundhati Roy published the essay “The Pandemic is a Portal,” exploring the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of the ongoing economic crisis and conflicts in India. Roy reminds readers that, while all lives are precarious, some are more precarious than others. She concludes with an image that is also a call to action:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

The key to Roy’s thoughtfulness in this image is that the “fight” for another world is visualized not as a war, but as an act of carrying a metaphorically lighter load. What would a hypothetical defeat of old systems look like? From the details of basic infrastructure to the nuances of public education curricula and everything in between, the lightness of “luggage” that she describes isn’t about leaving behind people or communities; it’s about leaving behind the old structures, the old stories.

What does all this have to do with Le Guin’s 1988 essay on narrative theory? In the ’70s, the term “Carrier Bag Theory of human evolution” was used by anthropologist Elizabeth Fisher in her research on early human development. Fisher suggested that early humans’ primary tool or “cultural device” was not the knife or spear or club, but rather the containers they used to carry food from the place it was found to the home. Le Guin, a decade later, borrowed this nonfictional device for her “theory of fiction.” She opens her essay not with a contemplation of genre, but with the anthropological insight that, in spite of the way the hunter/hero figure looms large in the collective imagination, evidence indicates that the majority of the sustenance of the so-called “hunter-gatherers” of early humanity was likely of the “gathered” variety.

At first grounding the discussion in these historical archetypes of the hunter and gatherer, Le Guin combines her straightforward, analytical prose with lyrical passages in the first-person voice of the gatherer-woman who carries on gathering with her children in tow:

Go on, say I, wandering off towards the wild oats, with Oo Oo in the sling and little Oom carrying the basket. You just go on telling how the mammoth fell on Boob and how Cain fell on Abel and how the bomb fell on Nagasaki and how the burning jelly fell on the villagers and how the missiles will fall on the Evil Empire, and all the other steps in the Ascent of Man.

It is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it’s useful, edible or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people . . .

Le Guin sets up the over-valued “linear, progressive, Time’s-(killing)-arrow mode of the Techno-Heroic” in comparison with the always-present “life story” that persists in “myths of creation and transformation, trickster stories, folktales, jokes, novels.” The truer story, she argues, can be represented better as a carrier bag, an ongoing gathering-up and letting-go, rather than the classic “man vs. x” narrative scaffold. But her essay is not just about rethinking fiction; it’s about rethinking the human story itself, rethinking the “Ascent of Man” and that which will follow. She invokes the famous opening sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey where a shot of early man’s first weapon—a large bone used for blunt-force murder—is thrown up into the sky and becomes a phallic space ship, “thrusting its way into the cosmos to fertilise it and produce at the end of the movie a lovely fetus, a boy of course, drifting around the Milky Way without (oddly enough) any womb, any matrix at all.” She does not condemn this individual film as a piece of art, but rather illustrates how this “Techno-Heroic” story has been more than sufficiently told and suggests that its overuse has limited our collective imaginations. Perhaps Kubrick’s experimental non-conclusion is hinting toward the same.

While the “life story” and “killing story” inherit certain classically gendered qualities (the carrier-bag-as-womb, the hero-weapon-as-phallus), Le Guin refuses to assign these frameworks into a binary. They cannot be opposites because one envelops the other, both of them in perpetual motion: “Conflict, competition, stress, struggle, etc., within the narrative conceived as carrier bag/belly/box/house/medicine bundle, may be seen as necessary elements of a whole which itself cannot be characterized either as conflict or as harmony, since its purpose is neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process.” This idea of continuity without resolution is one of the most important elements of the carrier bag theory. Imagining human stories as linear conflicts is not only problematic, but also simply not true; it goes against what we know about life cycles, world cycles, the ongoing circling of the Earth. In the bigger picture of the “life story,” there appear to be no fixed beginnings or endings—only changes.

In November 2019, a new small press called Ignota Books, an “experiment in techniques of awakening,” published a slim volume of The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Staying true to the spirit of the essay, it is not a stand-alone work, but a tying-together thread for a small bundle. With Le Guin’s essay at the end, this container also includes a thoughtful preface by the editors, abstract visual artworks by Lee Bul (that fittingly evoke organic movement), and a substantial new introduction by Donna Haraway that serves as a brilliant contemporary companion to Le Guin’s work. In the introduction, titled “Receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying With the Trouble Together,” Haraway artfully integrates Le Guin’s theory back into the nonfictional world from which it first arose. She focuses mostly on insights from contemporary environmental and racial justice work in Colombia, positioning the carrier bag theory in conversation with the methods of activist groups such as Asociación de Mujeres Defensoras del Agua y la Vida (the Association of Women in Defense of Water and Life), Movimiento Ríos Vivos Antioquia (the Living Rivers Movement of Antioquia), and the Indigenous Students Association of Universidad de Magdalena. In a fascinating move of form-meets-content, Haraway uses three literal carrier bags gathered in her research in order to illustrate her findings, incorporating the symbolic resonances of carrying as well as the literal embroidery and materials from which the bags are made into her piece.

Haraway’s presentation highlights how real-life communities are already writing an alternative story—and have been writing it, and weaving it, for a long time—in resistance to the seemingly dominant story of imperialist violence and oppression. The theory thus becomes secondary to the action itself: the defending of real-world water and the healing of real-world communities that techno-capitalist forces continue to threaten in the name of a tragically limited, “Techno-Heroic” idea of progress. The bag made by Movimiento Ríos Vivos Antioquia is stitched with a poignant verbal play in Spanish: Flore-Ser. It is a pun on florecer, to flourish or bloom, and ser, the verb “to be” which also acts as the common substantive equivalent for being (as in un ser vivo, a living being): blooming-as-being. Much larger than “winning” any given battle, here, the never-ending goal is simply to survive and thrive.

These ways of thinking are important because they help us to re-imagine the past, present, and future in a way that orients us toward more possibilities of collective, nonviolent—but never uniform—resistance of the status quo. Haraway writes, “It matters what stories we tell other stories with; it matters what concepts we think to think other concepts with. It matters wherehow the ouroboros swallows its tale, again.” What, then, does a “carrier bag revolution” look like? In this view of the human story, it’s already been happening every year and has been in the rhythms of change for generations, ever since the first gatherers realized that there were ways to hold so much more than what can fit in two human hands. The current carrier bag revolution is a salvage-bundle gathered up from the previous ones; it has no clear beginning and refuses to end.

Long-term change hardly ever happens in decisive “victories.” The legislative and cultural victories of the Civil Rights Movement, while worth celebrating, obviously did not eliminate racism; the fall of the Berlin Wall did not solve the question of how to govern effectively; the legalization of gay marriage has not eliminated homophobia in the United States. While a political “revolution” technically requires a sudden regime change by definition, even then, the real changing of communities and social structures is always continuous, evolving; it seems that regimes are not complete stories. While every example has its nuances and symbols—the Carnation Revolution, the Rose Revolution, and the Jasmine Revolution all acquired the aforementioned association with flowers, the blooming-as-being—the truth remains that change is never linear, never all at once, and never entirely predictable. It’s also never finished.

Nature provides abundant material for this “life story,” this carrier bag revolution. Wildflowers grow in scattered clumps, seeded by the wind and pollinated by the sticky backs of bees. The individual organisms spread out their petals in strange spirals, blooming and being and growing and holding themselves together until their time is complete, so that life can go on in other forms. The whole thing seems too precarious to possibly work, and yet it does. On another scale, scientists can analyze the shifting of faraway light and know for certain that the universe is still expanding; it stretches and spreads out its matter and energy on all sides like a vast three-dimensional rubber band. But gravity and other forces allow it all to coagulate into spheres and spirals, planets and solar systems and galaxies, holding themselves together in constant movement and change over time, carrying out their nonlinear revolutions. The whole thing seems too chaotic to possibly work, and yet it does.

There is plenty of room in our gloriously round and ever-revolving carrier planet. The metaphor of the carrier bag for a theory of storytelling or evolution or revolution is just that, a metaphor—a carrier bag for approximate meaning—but the lived experiences of violence and oppression are real. State-sanctioned violence against marginalized communities is part of that narrow-minded “killing story,” and now that story is finally losing. Life spins out new stories every day; the structures of power can only try and fail to contain it.

This piece was originally published on June 2, 2020.