Guest post by Scott Nadelson

Visual artists also get to do narrative. And metaphor, too. As if they don’t have enough already, these spoiled visual artists, with their museums and their fancy openings and their relationships with Icelandic pop stars. Must they also steal from poor, humble writers, who have so little to work with, who struggle to make meaning out of something as unassuming as dark marks on a white page?

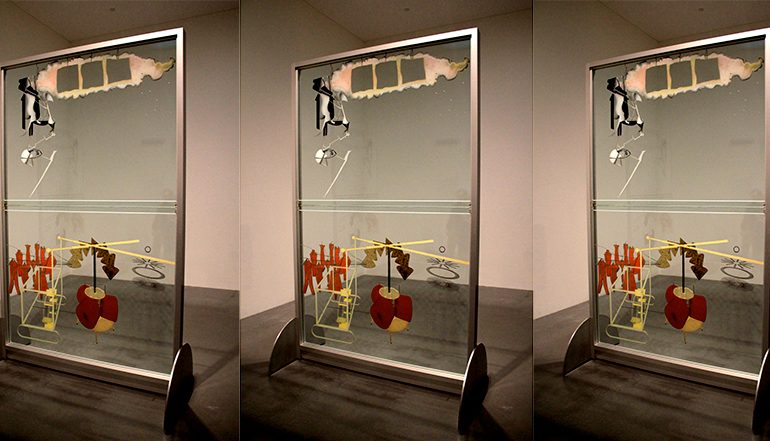

Of course, visual artists have been engaging not only with narrative but with language itself for nearly a hundred years. Ever since Marcel Duchamp prioritized idea over aesthetics, language has been an essential part of visual art practice. His most famous work,

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, would mean nothing without its title–how I love that wonderfully odd “Even,” which qualifies or undermines what it follows–or without the box full of notes that accompanies the construction.

What sparks my envy in particular about the way in which visual artists use language is that they never seem to worry, as I do, about words’ abstraction or elusiveness or obscurity. In fact, they seem to revel in these things, embracing them without hesitation. Take this sentence from Duchamp’s notes about The Bride, for example, which was later published as part of a piece he called The Green Box: “She accepts this stripping by the bachelors, since she supplies the love gasoline to the sparks of the electrical stripping; moreover, she furthers her complete nudity by adding to the first focus of sparks (electrical stripping) the 2nd focus of the desire-magneto.”

What the hell does that mean?

Who cares? Duchamp seems to say. Why should it mean anything? Or rather, why shouldn’t it mean whatever you want it to mean?

Because the visual artist has the benefit of being grounded in direct, sensory experience–there’s always that viewer in the room, present with the work–he is free to allow language its full powers of obscurity and elusiveness. And it’s this combination of the physical and the abstract that gives the work clarity. We can understand The Bride as a physical rendering of Duchamp’s abstract musings on desire and fulfillment, on mechanism and eroticism. Absent one or the other–the abstract thought, the physical manifestation–the work wouldn’t communicate anything.

My favorite piece from this year’s Whitney Biennial is one of the best examples I’ve ever seen of visual artwork that explores the meaninglessness of words, or rather, the almost-meaning of words, the sense that meaning is just out of reach. Marianne Vitale‘s video piece Patron is a manifesto of sorts, a call to action–but what exactly it professes, or what action it’s meant to provoke, is never entirely clear.

The piece is striking in its simplicity: the artist stands in front of a hand-painted black and white backdrop and addresses the viewer, the “patron,” directly. “Welcome to the future of Neutralism,” she says, though she never explains what Neutralism is. She tells us to stand up and “spit at the ceiling,” though why we should do so she doesn’t say. Her monologue moves from gross-out–“imagine your feet soaking in gopher urine”–to an assessment of the relative importance of various American states: New Jersey is good only for glue, she tells us. But her urgency never falters. What she is saying is the most important thing you’ve ever heard.

Patron is a send-up of art manifestoes, a satire of political speech, but it’s also a celebration of language, of pun and wordplay, of rhythm and voice. It takes pleasure in the sound of words absent of their meaning. It’s also hilarious at times, unapologetically playful, even goofy.

Less whimsical is a piece downtown at the

New Museum, in which language is an intervention, a commentary on the very act of visiting museums. Step off the elevator on the second floor, and a museum guard turns her back to you. Facing the wall, she sings in a mournful, heartbreaking voice, “You know, you know. This is propaganda.” Before you’ve seen a single painting or sculpture or video, you’ve encountered this lament, and if you’re like me, you’ve had your experience of the museum altered. You can’t look at a work of art without thinking about how it communicates a particular perspective or agenda.

This isn’t an actual museum guard but a performer of

This Is Propaganda by Tino Sehgal, an artist who took over the entire rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum this winter and whose work was recently the subject of a fascinating feature in

The New York Times Magazine. Sehgal doesn’t allow any images or videos of his work to be reproduced, so all the Guggenheim can use to represent the exhibit is an image of the artist’s name; even in the publicity around his show, language trumps image:

What I love about Sehgal’s piece is how much he accomplishes with so little. Seven words, and he changes your entire experience, not just of his own piece, but of art viewing in general. Of course he has the benefit of a live performer, a beautiful, haunting voice, a unique context. But in the end, it’s the words that direct us to the meaning.

Above all, the piece strikes me as an incredibly honest one, a work that turns its scrutiny on itself as well as on the pieces around it. Here is an artist who refuses to ignore the limitations of art making, and of communication generally; whatever you make, whatever you communicate publicly, is inevitably propaganda. But to recognize this, to own it, is to embrace the power of the message, to discover its clarity. Let’s not fool ourselves into thinking we’re separate from the world, the piece seems to say to artists, and to writers, too. Let’s be part of it, and to acknowledge what it is we’re doing when we place an image or an object or an arrangement of words into view.

This is Scott’s fifth post for Get Behind the Plough.