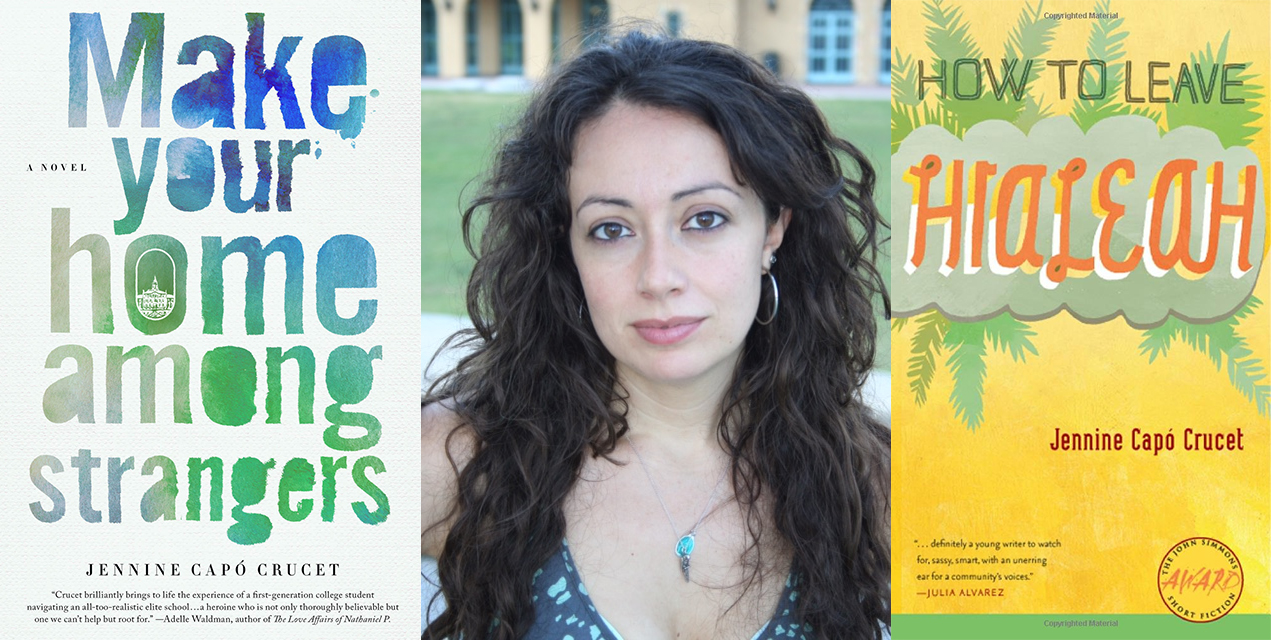

An Interview with Jennine Capo Crucet

I first met Jennine on the dance floor in a barn on a summer night at Breadloaf. Or at least I like to remember it that way. She’s an electric person, both in the flesh and on the page. She says the unexpected, and also the uncomfortable and necessary. She’s equal parts funny and fearless, irreverent and brilliant. Our interview, below:

MMB: I think of you as a writer who addresses the specific impact a place has on the human experience and shaping of self, but in a way that feels fresh and contemporary. In your first collection, How to Leave Hialeah, Charles Baxter praised you for writing a book that starts “with Cuban American neighborhoods and cultures and then sails off into the direction of the great themes: love, familial bonds, aging, and death. And resurrection.”

Your latest novel, Make Your Home Among Strangers, concerns the daughter of two Cuban immigrants, and one who chooses to leave Miami for a more privileged college environment. What do you make of the current dialogue in America on immigration, and how does this fuel your current work, if at all?

JCC: My family bought into the American Dream rhetoric in a pretty hardcore way. I was raised to think of this country as the best one on the planet specifically because it welcomed my family and gave them opportunities for a better life. I mean, my parents named me Jennine after the Miss America runner up the year I was born (though spelled differently, I think)—so it goes that deep for them. As I got older, naturally my own ideas about this country grew more complicated, particularly around the issues of immigration. I think what’s most disappointing for me about our current dialogue is how quickly the conversation dehumanizes the people these policies impact. And I thought about that a lot while writing Make Your Home Among Strangers: I wanted the book show how a larger national conversation impacts one person&mdashhow these policies eventually come to shape who we are and how we move through our communities. And what I thought about the most as I wrote certain scenes—namely the ones about the fictionalized version of Elian Gonzalez—was how little things have changed in the last fifteen years, how we’re still using the same broken system, how very disappointing that is.

MMB: You’re a serious writer with a sense of humor—an occasionally dark sense of humor. Any guiding principles or advice for other writers hoping to achieve that enviable mix on the page? How do you find the right moment for humor in a scene?

JCC: Anyone who knows me well knows I tend to say really inappropriate but absolutely honest things at possibly the worst moments: I pass this off as my “sense of humor.” If I have a guiding principle about humor on the page, it’s this: all (literary) humor is, is something showing up where it’s not expected and before we are ready for it. George Saunders explains this much more eloquently in The Braindead Megaphone:

“The comic is the truth stripped of the habitual, the cushioning, the easy consolation.”

So, to try to turn that into advice: The right moment for humor in a scene is just before you think there should be humor in the scene. Does that make sense? Probably not.

MMB: When my first book came out, I was surprised by how often readers and critics brought my biography into the reading of my work. Your books often feature Cuban Americans, so I imagine you encounter biographical readings as well. What’s your response to this?

JCC: It’s so uncomfortable when it happens, and sometimes it’s even really aggressive; I’ve had experiences where an audience member keeps saying “you” when what she really means is my narrator, and even after a gentle correction, she’ll come back with, Right right but come on, it’s you. My response, when I can do this without pissing too many people off, is to ask outright, Why are you conflating me with this character? Because the answer to that question is almost always something that person doesn’t want to admit (because you are both Cuban-American!), and in making them admit it, they recognize how ugly that assumption is.

But it still happens all the time, and I can’t imagine that white, straight, male writers get this as often. I really thought I’d avoided it with this novel by making Lizet a research scientist—a marine biologist—a fact we learn about her almost right away. But no! At one of the first readings I gave from this novel, a man came up to me after I read the opening, and he asked, “How long were you a marine biologist?” I tried to see this as a compliment—My narrator’s voice is so convincing that he thought this was memoir!—but this was after a lengthy intro (and in a context where it was clear I was not and never had been a marine biologist), so honestly, I just wanted to punch him in the throat.

MMB: You recently wrote a candid and moving piece for the New York Times called Taking My Parents to College. In it, you talk about sharing a mantra with your mother: Get back to work. What other mantras have you developed for motivating yourself, coping with criticism, and making your way in literature?

JCC: Get back to work is the biggest one, mostly because I use work as an escape from overwhelming feelings of sadness and self-loathing that would otherwise keep me trapped in my bed (ha ha ha!). Another mantra that runs through my head daily is Channel the rage, because I am often very angry for reasons I can’t always figure out, and so channeling it into something productive is really all I can do to avoid an ulcer. I’ve heard some writers say that rage and anger aren’t good places to write from; I would say that’s true for revising, but not at all for initial drafts. I would also argue that maybe those writers have a limited capacity for rage. I know for some people, rage shuts them down, so of course they wouldn’t be able to write from that place. But rage, for me, is like the sun, and I am like a gigantic and highly-efficient solar panel.

Related Posts

-

“As a writer, what history or current events do I have permission to write about?”: An Interview with Jihyun Yun

“As a writer, what history or current events do I have permission to write about?”: An Interview with Jihyun Yun

-

“You start out in difficulty”: An Interview with Dan Albergotti

“You start out in difficulty”: An Interview with Dan Albergotti

-

“To write about Geppetto is to write about fatherhood, and at the same time he is a creator of a monster”: An Interview with Edward Carey

“To write about Geppetto is to write about fatherhood, and at the same time he is a creator of a monster”: An Interview with Edward Carey

-

“One of the things I love most about literature is the possibility of inhabiting someone else’s consciousness”: An Interview with Kawai Strong Washburn

“One of the things I love most about literature is the possibility of inhabiting someone else’s consciousness”: An Interview with Kawai Strong Washburn

About Author

Megan Mayhew Bergman lives on a small farm in Shaftsbury, Vermont with her daughter and veterinarian husband. Scribner will publish her first book, a short story collection titled Birds of a Lesser Paradise, in Spring 2012. Her work has been published in the 2010 New Stories from the South anthology, Ploughshares, Narrative, One Story, Oxford American, The Kenyon Review, Shenandoah and elsewhere.