Bhanu Kapil: Hybridity and Disembodiment

Bhanu Kapil is a British-Indian writer concerned with migration, transformation, loss, and the hybrid text. In her slim, subversive books she considers bodies “at the limit of their particular life,” and the embodied prose she fashions to depict them are strange, broken, and revelatory. This is the case with Schizophrene, Ban en Banlieue and Humanimal, A Project for Future Children, three books that capture the frenetic experience of bodies on the cusp of change by allowing compression, repetition, and rupture to move and shape the text.

The world, we know, is full of stifled speech, with bodies packed full of things unsaid. Bhanu Kapil’s books seek out this cut-short expression as well as the bodies that hold it. These are bodies so marginalized by colonial, racial, and sexual violence that they are physically altered. Alienated from society, immigrant and minority bodies become, according to Kapil, schizophrenic and feral; the forms Kapil forges are in keeping with their estrangement. Rather than graft familiar, daily language onto their disembodiment and trauma–an approach disbanded by Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain–Kapil attends to the nuances of their thwarted expression, and allows the sensations particular to the repressed body to shape the text.

The act of writing, then, occurs both in the body and on the page. As Kapil writes in Ban en Banlieue: ‘The most realistic rendering I could make of this experience . . . would be to crawl on my knees.”

This duality and subsequent embodiment sees the texts in kinship with the bodies they depict. Schizophrene’s kinship is to the immigrant, schizophrenic body. Considering the Partition of India in 1947, the book assesses the myriad psychosomatic impact of immigration, and asks if schizophrenia might be among its effects. Schizophrene takes its form from the sensorimotor sequence, the result of unresolved trauma lodging as glitches, subtle movements, trembling, voltage. Therapists can track and complete these sequences to induce catharsis, and this is what Kapil attempts: “to release . . . a loop of distortion or contraction in the body” in the very fabric and flesh of the text.

Trauma is employed as a formal device, and because it is “rhythmic, touching something lightly many times,” the narrative thread is necessarily subtle and tenuous. Fragments coalesce and disperse, words and images seem to momentarily connect. The result is an internal narrative of sense and image memory, and the effect is hallucinatory, leaving the reader unsure of her footing:

What makes the city touch itself everywhere at once . . . like they city you live in now? What makes the wall wet, the step wet, the sky wet?

Ban en Banlieue also forgoes linear form in capturing the fraught intensity of a race riot in the suburbs of London in 1979. Ban is “a brown girl” walking home from school when she hears the sound of glass breaking, a sound she instantly understands as sexual, racial, and violent. Rather than run or take cover, she lies down on the road. To insert Ban into a more linear narrative, into “a literature,” would see her inscribed afresh with harmful ideology. Instead, Kapil writes “the increment of her failure to orient, to take another step,” and though Ban is slowly “progressed to meat,” her body functions as a remnant of the riot, as a visceral and astute kind of testimony.

The poetics of a riot, Kapil writes, are necessarily barbaric, hence the need to replicate violence with violent language: “Ban is crumpled like a tulip: there. A wetness, that is, with limbs.”

Kapil has described the book as a violent discharge, and “discharge” as supposed to “disclosure” is an important distinction. One is automatic and unintentional, the other orchestrated and confessional.

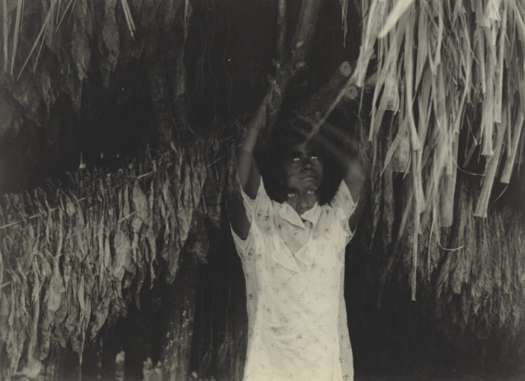

In Humanimal, a Project for Future Children, Kapil again draws on historical matter and portrays female bodies bending out of shape to literalize their oppression. Amala and Kamala were two girls found living with wolves in Bengal, India in 1921. While on a mission to convert the tribal populations, Reverend Joseph Singh heard of “two white ghosts” roaming with a mother wolf and her cubs. Singh tracked and killed the wolves, and for the next decade attempted to school the girls in language, upright movement, and “a moral life,” Despite Singh’s efforts, Amala died of nephritis within a year of capture. Upon being “recovered” from the jungle, Kamala’s bones were broken and reset to undo her four legged gait. She outlived her feral sister, but died of TB at the age of sixteen.

Kamala’s quadrelupal stance is among the factors that determine the book’s form, with Kapil implementing an “antidevelopmental prose” that corresponds to her hindered, hurting physicality. Sarah Dowling writes that Kapil creates “a loping text . . . that replicates the shock and awe of civilizational violence to which the wolf girls were subjected.”

In essence, Kapil seeks out an alternative telling for two girls who suffered for their non-normative bodily difference. She considers the imposition of language as a kind of violence, and attempts to capture Kamala’s feral sentience in prose particular to the senses and the knowledge they provide:

I want to stand up but I can’t do that here. They would know I am a wolf by my sore hips, the look in my eyes

The doctor who attended to the girls during this time writes of Kamala: “I was changing a unique but . . . poorly operating girl to a normal pattern of a woman.” Humanimal might be read as an attempt to preserve this unique, feral pattern, and offers one way for Kamala to speak on her own terms. As John Berger writes of Jean Basquiat, the world is depicted “in a language that is deliberately broken–ontologically broken.”

Reading Kapil’s hybrid work, there is a keen sense of expression bursting the body’s boundaries, and the urgency that ensues is the urgency of something being revealed for the first time. The world may have proven too hostile, too crass and too limited, but Kapil proposes the page as a site where such repressed and radical perspectives can manifest. Operating from a position of witness and empathic interloper, Kapil’s broken forms allow bodies to speak without the filter of conventional language and narrative. They are forms that break away from convention, reaching beyond structures that have proven insufficient. Fuelled by a poetics of retrieval and replete with restorative gesture, they are texts the reader feels could not help but, at last, come into the world.