Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse: Beauty and the Japanese Tradition

The posts in this series, Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse, consider various traditions, ideas, and/or authors in the search for imaginative ways to give voice to our current ecological disaster.

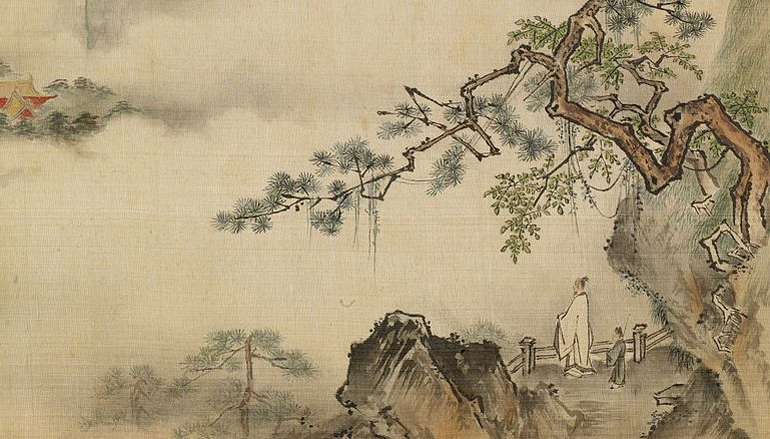

In the late twelfth century Japan, a one-time bureaucrat and sometimes poet named Kamo No Chōmai retreated into the mountains surrounding the capital to live as a hermit. He had witnessed devastating earthquakes, fires that engulfed whole districts of the city, suffered the caprice of rulers, and saw famine take the lives of thousands. Horrified by such events, tired of the petty jealousies and the disappointments of living in society, he turned his back on the world.

During his retreat, he would compose one of the most famous works of Japanese literature, Hōjōki, or Record of My Ten-Foot-Square Hut, a short work that famously opens with a reflection on the mutability that undermines all things and which drove him to seek his hermitage:

The river flows on unceasingly, but the water is never the same water as before. Bubbles born on the surface of the still places disappear one moment to reappear again the next, but they seldom endure for long. And so it is with the people of this world and the houses they live in.

Over the course of Chōmai’s reflections, his despair evolves. The same wind that tore through the city, destroying houses and lives becomes the wind rustling in the maples. The sound of the streams, the birds, the cicadas, and all things that make up his surroundings serve as reminders of the impermanence and of his own approaching death. At the same time, are the source of intense aesthetic pleasure.

Chōmai’s experience is emblematic of a classical Japanese aesthetic that is immersed in a sharp sense of sadness and despair over this changing, impermanent world. Unlike Platonic and Christian ideas of beauty that still pervade many of our concepts of beauty, in the Japanese tradition, beauty is not an aspect of the eternal or the transcendent. It is immanent, feeble, and perishable. For the cultivated individual, the capacity to behold beauty is only possible because they recognize that inherent sadness that all beautiful things must pass.

One of the many things I have found so moving and gripping about classical Japanese literature is how concrete the worldview is. Here is a sensibility that is deeply enmeshed in the world and looks for beauty in the imperfections of nature, in the corrosive effects of time, that is, within life’s inherent flaws.

Of course, medieval Japan is a world apart from our globalized twenty-first century. Yet, the more I think about how the traditional Japanese aesthetic involves the continual practice of cultivating one’s ability to experience beauty in a world that is marred by natural disasters and sorrow, the more I think there is something here that can help us to behold beauty amid our current environmental disasters.

Whether it’s brought on by humans in the form of clear cutting, poisoning rivers, or by a natural catastrophe, humans have had to confront destruction, death, and change for millennia. As our planet rapidly changes into a hot, over-populated world, many, myself included, are haunted by the lost beauty of a world that was once wild, not mechanized and administered for human consumption. It is easy to despair over this, but despair may be imaginatively limiting.

Attentive to the passing of all things, recognizes that all that nourishes, sustains us and gives us joy, is ephemeral, the Japanese tradition nonetheless does not settle into a tragic vision. It takes this inherent sadness and from it, cultivates a sense of beauty. This involves the austere and difficult work of being in the world, not escaping to a transcendent fantasy or a timeless realm, but staying with the ugly truths that make up our present world.

For writers and artists now witnessing the unprecedented destruction of the natural world, this may be a supple way to confront our environmental situation, one that is different than the apocalyptic despair, the dismal future and world-in-ruins motif that has become something of the standard way writers deal with our environmental disaster.

In a way, the aspects of the Japanese tradition I have outlined pose an imaginatively demanding task to find beauty, peace, or tranquility in the worst parts of our environmental apocalypse. Neither optimistic nor laden with despair, it is a way of being present to the sorrows that are a natural part of life and refining one’s perception to find beauty in the brokenness of the world.