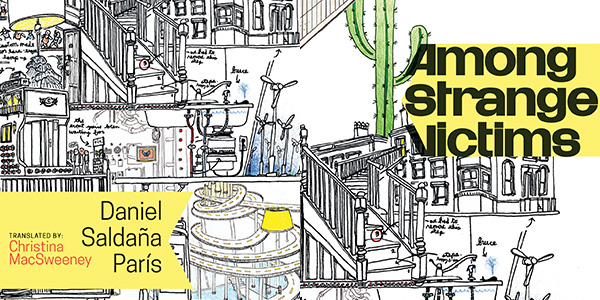

Daniel Saldaña París’ Among Strange Victims Is the Book You Need in the Post-Trump-Visit-to-Mexico Era

Of all Mexican novels to read in this post-Trump-visit-to-Mexico era, Daniel Saldaña París’ Among Strange Victims (Coffee House Press, translated by Christina MacSweeney) reigns supreme. Not that it’s an overtly political novel, but it is one that explores the unbearable absurdities of living in this world. Think Jean Paul Sartre meets Juan Villoro and that’s the kind of existential magic you get in Saldaña París’ book, which not only explores the absurdities of power structures and institutions in Mexican society but actually informs this now seminal question that many Mexicans (myself included) have been asking ourselves over the past week and a half: How the hell did Donald Trump—of all people—get invited to Mexico (and can we get a new MX President, please?)

Saldaña París doesn’t answer those questions directly, but his words do serve as some salve to the Mexican soul, if only through his cutting satire, which pokes fun at power in ways both direct and indirect. Through his protagonist, Rodrigo, Saldaña París explores an almost institutionalized Mexican angst amidst his interactions with various facets of power, be it Mexican bureaucracy, academia, corruption, narcos, marriage, or his own relationship to his mother and her Spanish academic boyfriend, Marcelo.

Among Strange Victims starts off chronicling Rodrigo’s malaise in Mexico City, an ache that seems to come as much from his desire to grow beyond his circumstances as it does from his general misanthropy and subsequent boredom, which he inhabits every day through monotonous routine. Rodrigo is content enough in his job at a government funded museum where he writes anything that needs to be written—pamphlets, speeches for the director, press releases, letters—and works under the self-appointed title of “knowledge administrator,” words he saw on a periferico billboard advertising a degree program in just that: knowledge administration.

In the book, Rodrigo states, “I am not particularly happy. And moreover I don’t think I’ll ever study that degree program. In fact, I’m never going to study any degree program. In fact, I’ve never taken any course, at least not all the way through,” a thread which proves to be a source of tension between Rodrigo and his mother who not-so-subtley worries about him from afar. Rodrigo is hardly more than a spectator in his own life.

This comes to a head early in the novel when a prank love note written on his behalf makes its way to his work colleague Cecilia, and Rodrigo becomes accidentally engaged and married to her. And while marriage proves to be a short-term escape from the general boredom of his life, that brief stint of happiness too gets complicated when, one day, Rodrigo enters his apartment to find that someone has literally taken a perfectly coiled shit in the geometrical center of Cecilia’s favorite tiger-striped bed spread. Nothing is stolen. No signs of break in seem to be apparent. Just the shit in the center of the bed. Rodrigo says:

Either the poo has meaning or it doesn’t. If it does, then it can be thought of as a sign and is waiting happily in its loathsome image for me to venture onto the course of its exegesis. If it has no meaning beyond that of perturbing me, it can feel satisfied with itself, can pull up its pestilential anchor and set sail for other, more fragile sensibilities.

It’s only later in the novel that an adolescent American, Micaela, pulls Rodrigo from his funk with promises of time travel and the coil of shit is put into perspective along with the rest of his life.

Since Trump’s visit to Mexico, us Mexicans have been forced to confront our own proverbial shit in the geometrical center of the bed. Luis Videgaray—President Peña Nieto’s right hand man—was only the latest to confront this mess, stepping down last week in the wake of the political fallout following Trump’s visit. Existential angst amongst the populous ensues. And we can’t help asking ourselves, Is this all some cruel joke? And if so, what does it mean? Did we marry Peña Nieto on accident? Can we go back in time to fix any of this stuff?

The real life absurdities surrounding Trump’s visit are definitely stranger than the fictional absurdities Rodrigo faces, though I can’t help but wonder if somehow these narratives are cosmically linked. Daniel Saldaña París’ pulse on the Mexican psyche feels that precise, that honest, that timely.