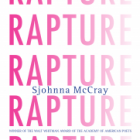

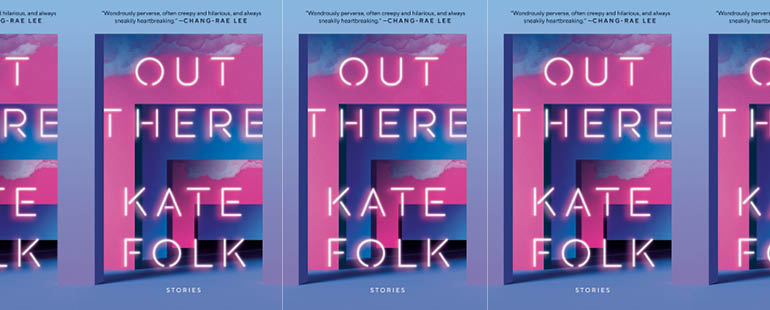

Desire and Destruction in Kate Folk’s Out There

Out There

Kate Folk

Random House | March 29, 2022

In Kate Folk’s debut short story collection, bodies want monstrous things, and the perils of human desire become the stuff of nightmares. Often, the characters get exactly what they want, meaning the stories are powered less by conflict than by an amplification of the initial, off-kilter impulse. Perhaps the clearest example of this is “Doe Eyes,” which begins, “I get this idea that I’ll go out into the woods and get shot.” That’s what the narrator wants, plain and simple, and the story unfolds around that central desire. At first, the narrator explains the root of this desire by saying that if the hunters accidentally shoot her, they will be convinced to “put off killing for good” and she’ll win her husband back.

The story’s structure is reminiscent of the playground cycle of dare, double dare, double-dog dare. First, the narrator goes into the woods dressed in brown corduroy pants and a brown sweater to rustle leaves within earshot of some hunters. When that doesn’t work, she goes to the sporting goods store and buys camouflage, then jumps out from behind a tree after an archer has missed his shot at a deer. Then she parades camo-clad before a group of hunters armed with shotguns. Finally, she solicits hunters for a focus group via Craigslist and asks if any of them have “ever fantasized about shooting a person.” She reaches an agreement with the hunter who says, “Sounds kinky.” Soon, the narrator’s initial desire gives way to ambivalence, yet despite that ambivalence, the narrator meets the hunter who has agreed to shoot her.

Ultimately, “Doe Eyes” becomes an exploration of consent and agency. The hunter brings his friends, who have placed bets on whether the shooting will actually happen. One of the friends says, “You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do,” at which point the other friends quickly jump in with reasons why she ought to go through with it. The story ends perfectly, as the initial desire is fulfilled, but the person who set that fulfilment into motion has become a subject rather than an agent of action:

‘You ready?’ one of them says.

I say yes before realizing he wasn’t talking to me.

Folk’s narrative voice makes even the strangest, most self-destructive desires seem reasonable. But Folk also beautifully allows those desires to change or become obscured. The stories in Out There exist between the strange and the familiar, and the ambivalence that characters feel about what they’re doing or what’s happening to them—even when they’re the ones who single-mindedly set those events into motion—makes them feel all the more real.

We see this also when the protagonists are putting their bodies on the line for love. For instance, “Heart Seeks Brain” begins with a happy hour conversation between the narrator and a co-worker. The conversation is familiar, as the women lament their imperfect bodies, but rather than complaining about weight or acne, these characters long for “smaller, daintier kidneys” but take solace in having, for example, an “abnormally slender liver.” It turns out, love is expressed by literally removing bits of another person’s body. In what could be a thesis of the collection, the protagonist explains, “The more someone loves you, the more he’ll want to meddle with the most vital parts of you, and vice versa. The only way to not hurt someone is not to love him enough, to remain unmoved by the thought of his organs pulsing beneath a thin layer of skin.”

The genius of this story is in how Folk discusses these strange desires using utterly familiar language to highlight how much we give and take in pursuit of our own desires. For example, in a haunting confession reminiscent of notches on a bedpost, the narrator’s friend says, “I’ve got jars at home in a mini-fridge. It was like a sport in my twenties. Once I had a piece of their liver, I lost interest, I knew I had them.”

The narrative drive of this story is not one of a character changing as a result of obstacles. Instead, the energy of the story comes from the gradual revelation of details. Folk’s balancing act is to up the ante by revealing more and more monstrous desires, while at the same time consistently using language with clear analogues to how we talk about contemporary dating. As the story builds toward revealing what the narrator’s taboo desire is, it also spotlights the absurdity of real-world romantic tropes and rituals.

This collection is consistently moved by what pulses beneath a thin layer of shelter. Houses function as proxy bodies. In “The House’s Beating Heart” and “Moist House,” houses are physical beings, and their desires have serious consequences, while “The Head in the Floor” is—believe it or not—exactly what it sounds like. In “Shelter,” Reese is obsessed with a mysteriously locked storm shelter in the house that she shares with her partner, who spends long hours at the recording studio. Language about the house is explicitly physical: “It was rejecting her as a body rejects a foreign object.” This link between Reese’s physical self and her shelter only grows as the story progresses. In blurring the line between home and the body, Folk is able to make the body’s wants and needs larger than the skin allows. And by placing human characters at the whim of these unsafe shelters that seem almost human, she elegantly illuminates our own destructive tendencies.

The title, Out There, refers to putting oneself out there, but also to the engine that powers these stories. There’s a sense of the improvisational yes, and… at work here, which creates stories that are deliciously strange and unsettling yet uncannily familiar. Reading these tales feels like traveling deeper and deeper into a house of horrors, but it’s also immensely enjoyable. In my notebook, I wrote, “I love that the engine of these stories often seems to be, simply: here’s a weird thing that happens, and here’s how it gets weirder.” That’s underselling this collection, though, because the weirdness always brought me back to my own body and my own understanding of home, love, and desire. This collection is “out there,” yes, but in it you’ll recognize what’s inside a person’s heart and body too.