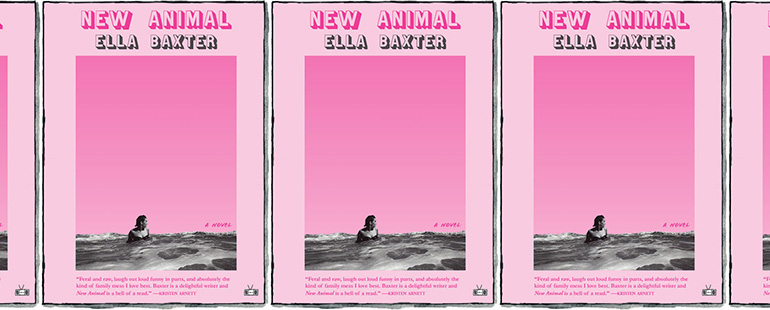

Disconnect and Dissuasion in Ella Baxter’s New Animal

New Animal

Ella Baxter

Two Dollar Radio | February 15, 2022

In Ella Baxter’s debut novel, Amelia, who works as a mortuary makeup artist, thinks she knows death inside out—until she loses first her friend and then her mother, in quick succession. What happens next is an unraveling of her mind. She jumps from one bad sexual experience to another yet remains “untouched” by emotions; she feels that she’s being asked to comprehend and process too much, too soon. Unable to cope, she runs away.

This premise threatens to flatten the character and make the plot of New Animal too predictable, but Baxter’s crackling prose keeps the ship afloat. The novel is a pacey read, a soulful comedy, and an intimate case study of a young person trying to put her life together. Much of this comes from Amelia’s job, which offers a refreshing, considered look at death. “I wish,” Amelia thinks, “people . . . could see what I do. Then perhaps they could feel that dark things aren’t actually always so dark. Dead things. Bone things. Blood and skin and matter things.”

Baxter’s evocative descriptions of Amelia’s job are poignant, thrumming with a sense of visceral understanding. Her descriptions of her work point to the inhumanity with which dead people’s loved ones think about them after their passing. “Give her face a fresh coat of paint, and put her in a dress that she never even moved in,” Amelia remarks. She demystifies not only death but also the logistics that follow. We see the humanized, ironic work that happens after someone dies.

Later, however, Amelia thinks about how “life rests like a layer of chiffon over a body: one puff of wind and you’re dead.” This leaves the readers cold, assuming that life is not dear to Amelia at all. In a way, though, Amelia’s feeling is justified. Her daily dealings with death lend the whole concept of it a certain level of levity for her. They make it mundane, almost ritualistic in a prosaic way.

In the first handful of New Animal’s chapters, Amelia ruminates in an affecting manner about dead bodies and people’s emotions about them. About the paleness of dead bodies, she says: “The deceased are beyond beautiful, but only because they are so emptied of worry. Everything tense or unlikable is gone.” This makes the reader wonder why Amelia would be so cold and removed from her own mother’s dead body; at the news of her mother’s passing, she leaves the city, then the country. Even though she knows that her brother and father need her, she flees, going to Tasmania on a whim. Later, we learn how she was unable to deal with the death of her close friend Daniel. When she visits the cliff from where Daniel died by suicide, we see how she struggles with expressing emotions, and that the loss leaves her feeling empty.

Amelia then tries, unsuccessfully, to seek out fulfillment through sex, which is often bad and rushed into. In these moments, Baxter’s writing shines a light on the human body as a vessel for experiences; these are the times when Amelia is shown at her most lost and vulnerable self. With profound descriptions of the human body, Baxter is able to create a tender, intellectual aura around sex. In the end, however, Amelia’s sex does not allow her to reach what she’s seeking. She is still removed, detached, and running away from her emotions.

In this way, New Animal packs a compelling tale in a narrative style that is equal parts caustic, wry, and nervy, and reflects the ways in which millennials continue to be stymied by the world around them. New Animal signals the entry of a new voice in fiction that is proliferated by disconnect and dissuasion.