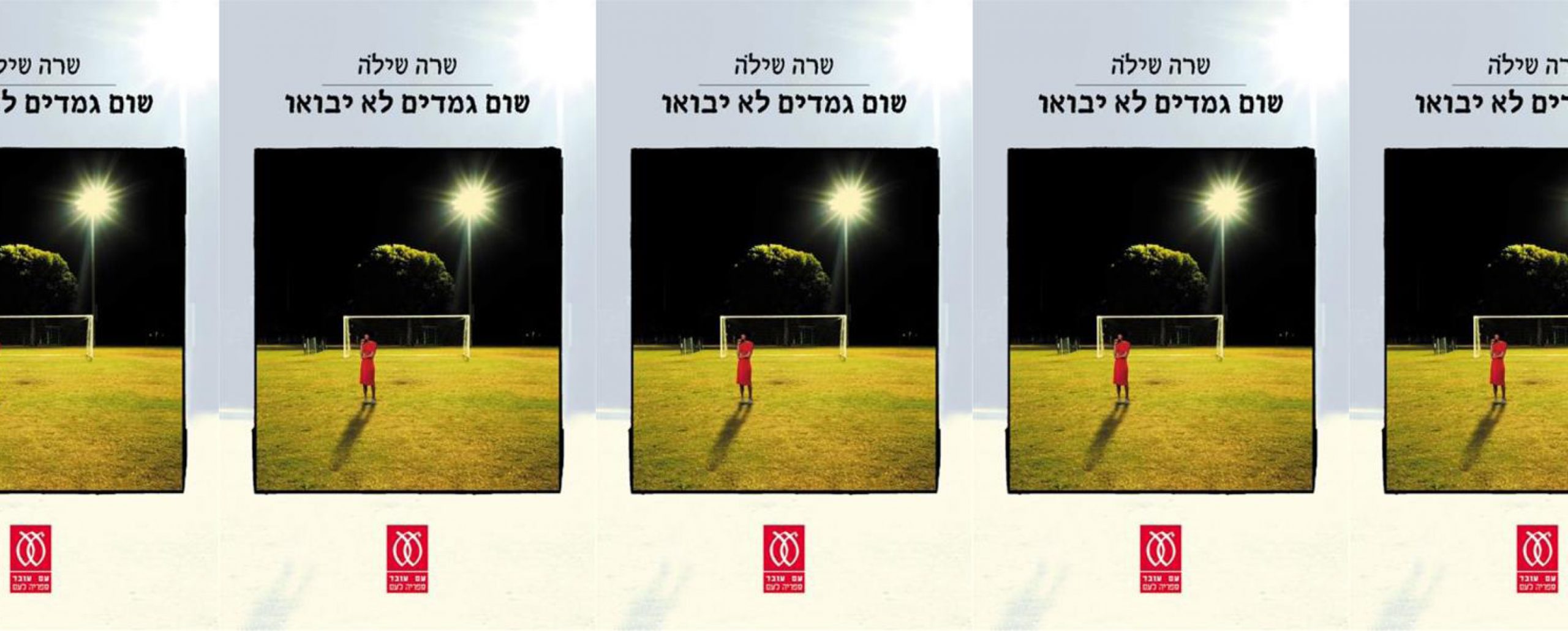

Gnomes’ Depiction of Tragedy

A man dies suddenly in a small town in northern Israel. It is the kind of town Israelis call “a hole”—remote, unappealing, and forgotten by the government. No one can say for sure what caused the man’s death. A bee sting, a slip on some cooking oil, a heart attack—all of these occurred, but because the man was alone, no one can say what led to what. This is the premise from which Sarah Shilo’s 2005 novel, Gnomes, takes off.

Much like the cause of death, the future of the man’s widow and children is shrouded in mystery. They live on Israel’s border with Lebanon, under constant attack from Hezbollah rockets, away from the attentive eyes of social services, and denounced by the deceased man’s relatives, who have taken over his falafel business but refuse to support his family financially. Lacking any kind of support, six years after the death, trauma has solidified into the foundation of their lives. Gnomes explores the repercussions of this truth, each chapter focusing on the perspective of a different member of the family.

The man’s widow is morbidly depressed. Grieving constantly over the loss of her husband and only lover, she is exhausted and overworked as she tries to hold a job while caring for her six children (two of whom—twins—were conceived shortly before the man’s death). Her life is pain and sorrow and a refusal to move on from memories of the past. She shares her pain with no one, continuing to pile responsibility on top of burden—nearing her breaking point—and receiving no emotional aid. As a result, she fails to notice her children’s distress, instead focusing her limited energy on keeping them fed and alive.

The eldest son, whose bar mitzvah party was the family’s final celebration before the death—and on which the family blew the majority of their savings—decides to act as the new man of the house. His job brings in most of the earnings, so he allows himself to make the rules. When his baby brothers are born, he begins to share a bed with his mother, to help care for them and to provide them with the illusion of a father. In the most formative years of his life, he experiences an excessive intimacy with his mother and a delusional sense of family, and the role switching takes its toll: nearing age twenty, he finds himself collapsing under the weight of responsibility, obsessed with sexual thoughts about his mother and fantasizing of buying an apartment in central Israel, where he dreams of living with his mother and the twins as a separate family unit.

The dysfunction of this dynamic intensifies across the book: the kids drop out of school, bills go unpaid, and trauma multiplies, unchecked. The couple’s two middle boys, who share a chapter, are forgotten and ignored by the rest of their family; they grow up wild, scheming fantasies about training a bird of prey to attack potential Arab infiltrators—with tragic results.

Each family deals with death differently, and perhaps there is nothing quite so unusual or deadly about this particular family’s process of grief. But to process trauma in a healthy way, to be able to come back from it in some capacity, one requires some form of emotional and physical support. Though the family of Gnomes shares one living space, and also dwells in a small, close-knit community, each member is alone and isolated in their mourning. This isolation has a cumulative effect.

Such moments are where institutionalized aid systems come into play. But when families live on the periphery, away from a government’s attention and with no one to inform them of their options, resources are often either unavailable or under-utilized. Even when programs are accessible, people who have become accustomed to a lack of support often feel so resigned to their isolation that it might not occur to them to find out what they might deserve. In the town in which the novel takes place, people have accepted corruption as the law of the land. In the daycare where the woman works, structural renovations come only after flirting with a municipal official. Families seeking an apartment in a housing project must vote for the “correct” party. The book’s eldest son receives promises of untold advancement on the condition that he does his boss’s bidding and curries favor with a political leader who visits town. Under such circumstances, it should come as no surprise that help is not sought when tragedy hits. Under such circumstances, tragedy is often not even identified.

The daughter in Gnomes is the only one who seems truly aware of the depth of the trauma her family is experiencing. The chapter told from her point of view shows her running around town in a panic, feeling that she must tell her baby brothers the truth about their father’s identity, that she must find a way to save her family from the rumors of incest that have already begun circulating. And she seems to know that this is not just the story of personal tragedy—it is the story of a society that is either unequipped or unwilling to care for its members. The story of people orphaned by their own country. As she hurries home, the sister is caught by a siren, warning town residents of an incoming rocket attack, and accidentally rushes to the wrong bomb shelter. Surrounded by neighbors from a nearby building, she listens as their gossip paints a picture of a town that has accepted its inconsequence. She senses how limited her power truly is in changing her family’s situation. When she returns home, she begins to tell her baby brothers a story about a mother who loses her body and her identity, hoping, through the story, to reveal the truth to them. But as the story progresses and her brothers grow more and more despondent, she knows that the truth might be revealing but that it won’t change the hopeless circumstances of their lives.