Hanne Darboven’s Exploration of Time

Plato’s Socrates originally suggested that writing was a technology of forgetting, since by writing down a thought, one no longer needed to remember it. The thought had been externalized and preserved through writing, but it was no longer a thought—it was something else. For Socrates, thought was inextricable from the temporal, embodied person. And yet we only know of Socrates’s dialogues through Plato’s written records of them. In this way, writing becomes a form of time travel, a prosthesis or artifact by which contemporary readers might access the past. Later, in his Confessions (AD 397–400), Saint Augustine asked how one might measure present time, since it does not occupy space and can only be perceived in its passing from future to past. For Augustine, the present as an instantiation is ungraspable; we can only recognize the present in its “threatened loss.” Much later still, in Being and Time (1927), Martin Heidegger attempted to show how Being (ontology) is coterminous with time. The Being of all beings shows itself through its historical and finite context. Heidegger writes that “the central range of problems of all ontology is rooted in the phenomenon of time correctly viewed and correctly explained.” Yet we cannot grasp the present any more than we can grasp the whole of Being. To theoretically grasp something, which is to say to understand it, is only to fix that concept in its historical moment. For the German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven, we cannot view history as a universal history; rather, our present simultaneously shapes history and is shaped by history. Darboven thus sums up her process: “I do not describe, I inscribe.” It is primarily this inscription of and interconnection among writing, thought, time, and existential experience that motivates her visual and conceptual artworks.

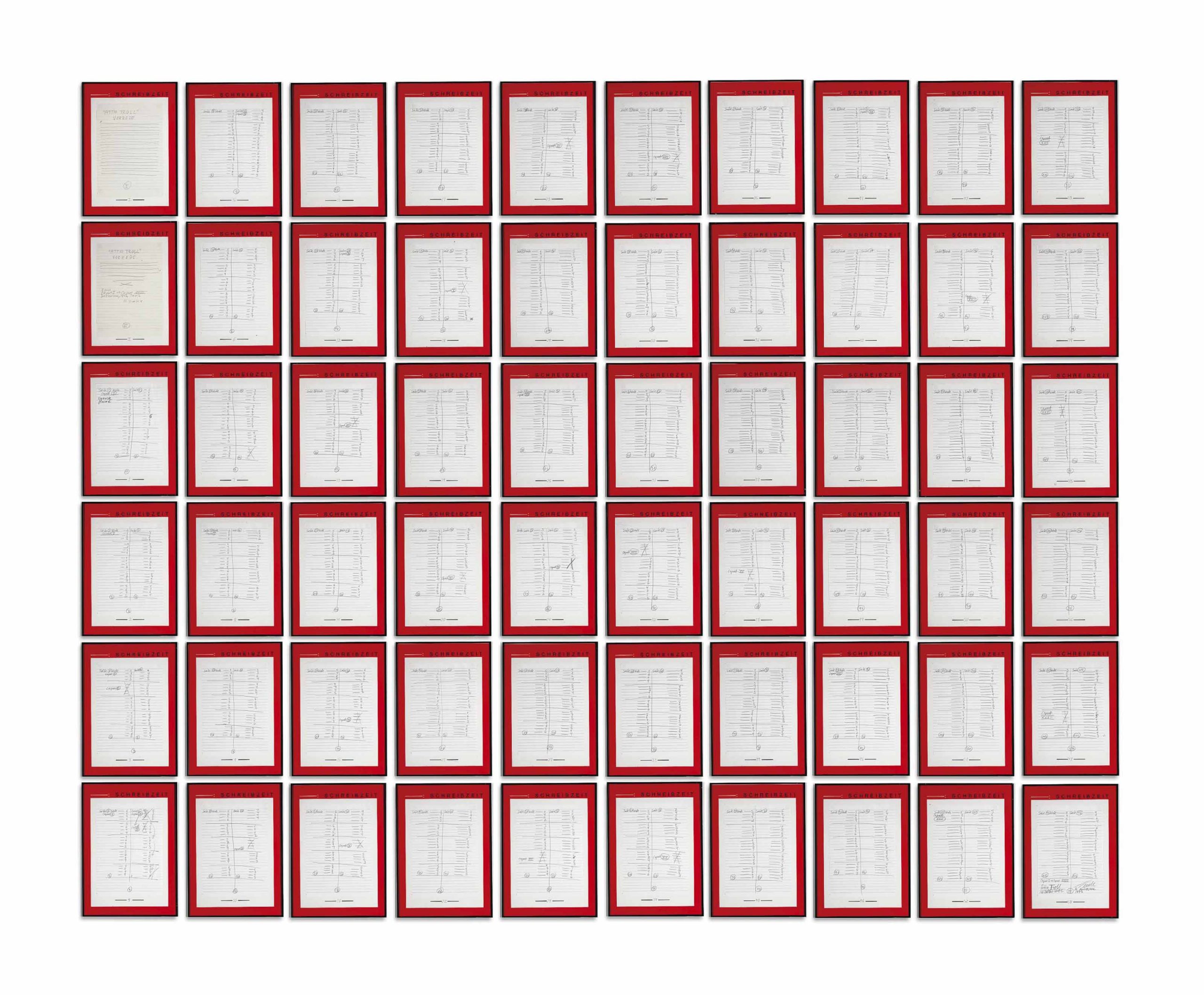

Darboven’s Schreibzeit (1975–1981) or “Writing Time” is a book that contains a long, handwritten series of checksums: days, months, and years are calculated and recalculated according to an abstruse yet fixed system of the artist’s creation. In some ways, it can be seen an attempt to rationalize something as impermanent and immeasurable as the present, something that does not occupy material space. The word rationalism itself stems from the mathematical process of deriving ratios, and Schreibzeit calls into question some of the relationships we assume between time as a quantifiable essence and time as an abstract numerical value. It is possible that the writing systems we currently use to represent ideas of history and time are neither appropriate nor comprehensible, whereas the calculative system that Darboven has created straddles the line between graphic illustration and written analysis. She often deploys charts, calendars, and strange marks that resemble waves or maybe cursive, lowercase ‘u’s bordering on asemic writing, and places them against and alongside poetic and philosophical passages from Hölderlin, Valéry, Rilke, Baudelaire, Brecht, Sartre, Heidegger, and others. In this way, Darboven deconstructs distinctions between space and time, image and text, art and theory. Because an audience is left without a clear interpretive model for Schreibzeit, it re-routes the viewer’s awareness to the activity of writing itself and the time that it occupies, rather than understanding Schreibzeit as a transparent historical artifact. According to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Darboven’s work “emphasizes process and duration” and “makes time both the raw material and the subject of her art.” Similarly, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam notes that “Darboven regards the artwork as a construction that is the result of analysis, calculation and planning.” Though she was primarily known for her large-scale installations of painstakingly handwritten tables and numerical calculations, Darboven considered this a form of writing, free from both representation and expressive emotion.

The obsession with which Schreibzeit pursues its analysis, calculation, and planning may point to a kind of perverse absurdity in a totalizing rationality in which “correctness” is reducible to number or formula. That is the impulse of rationalism: to make the universe legible by comporting it with a calculable model. The checksums in Darboven’s work are compulsively repetitive—yet refuse the purpose of calculation in the sense of arriving at a sum. They seem to exist only as a matter of doing the same thing over and over again, caught in a rigid, incoherent system. In Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), one of the major texts of the Frankfurt School that analyzed the rise of Nazism in Germany, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno describe the dangers of a totalizing rationalism and order that, in their extreme forms, pass from knowledge and understanding into mythologization. There is both the hope and belief that reason can shape and control reality, and the Western paradigm often assumes that because the rational mind sees the world in a certain way, that it must be all there is to the world. Nothing escapes this totalizing impulse; rationalism disqualifies any other form of discourse in its access to truth if it is perceived as “irrational.” Horkheimer and Adorno write, “Enlightenment stands in the same relationship to things as the dictator to human beings. He knows them to the extent that he can manipulate them. The man of science knows things to the extent that he can make them. Their ‘in-itself’ becomes ‘for him.’ In their transformation the essence of things is revealed as always the same, a substrate of domination.” Rationalism hates ambiguity, and it may be an uneasy thought that time somehow exists outside of our precise control, measurement, or representation. The slippage of present from future to past resists articulation through a computational model where everything can be made legible.

For a scholar like Thomas Ebers, Darboven’s work is a meta-consideration of the possibility of historiography. In his essay, “Filled Time: Hanne Darboven and the Phenomena of Time Histories,” (2015) he argues that “Darboven’s writing constitutes a specific kind of explicit visualization of the passage of time that is inherent to the act of writing.” Though Schreibzeit is presented as a book, it is artwork meant more to be seen (apprehended) than read, since, as Ebers argues, reading is a kind of “harvesting and gleaning,” a cherry-picking that has more in common with collecting. Darboven once asked, “Is there time without history?” In Schreibzeit, she seems to suggest not only that our present is always shaped by history, but that history is also shaped by the present, since “history” is artificial and constructed. History carries a temporal index, and each account of history is the subjective selection, differentiation, and ordering of that index. Walter Benjamin, in his essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” (1968) writes, “History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogenous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now.” To fill a historical fact with the presence of the now is to throw its meaning into flux. History is not historical by virtue of causal connection alone, but rather, as Benjamin argues, “It became historical posthumously, as it were, through events that may be separated from it by thousands of years.” History is retrospective, a thinking that is informed by both past and present, and which is always a transition into the future. We do not so much recognize the past “the way it really was,” but as an abstraction, filtered through our own imagination. Darboven is not interested in representing history through imitation, but through a high degree of abstraction, which may be the only access we have to history. After all, as Ebers points out, if one were to attempt to represent history through imitation, “How is a selection to be made; which individual events within the stream of time are significant? That they are or could be is alluded to by Darboven’s conversion of the calculated dates into a written computation.”

For others, like the scholar Elke Bippus, Darboven’s practice is semi-autobiographical, deconstructing the division between autobiography and history. In her essay “‘Seeing, of Course, Is also an Art’: Writing-Reading as an Aesthetic Labor of Mediation—on Hanne Darboven’s Work with Writing,” (2015) she describes Darboven’s non-linear presentation of time and writing as “a shapeable, heterogenous space.” Schreibzeit offers a syncretic vision of history and memory, one that weaves philosophical and cultural history together with personal history. Process and duration are performed by the labor of the singular artist writing by hand over several years’ time, rather than through mass mechanical reproduction. The art object of Schreibzeit becomes its own self-documentation as it accretes Darboven’s sketches and diagrams. Darboven once commented: “I rewrote by hand in order to be mediated myself by the mediate experience.” So not only is Darboven engaged in the writing of history but also the creation of it, since history is mediated by the writing subject; and not only is she creating this history, but she is also engaged in a process of autopoiesis, or self-making, since the writing subject is an inextricable part of history. Darboven might then be attempting to perform one final deconstruction: the division between epistemology and ontology, knowledge and being. Writing would thus be a simultaneous production of knowledge and a constituting of the writing subject.

How do we apprehend something as slippery as the present, and when does it pass into history? If anything, Schreibzeit shows us that there is no outside, atemporal vantage point from which to answer this question; we are coterminous with time. Darboven’s calculations will never produce a final sum no matter how many times she repeats them because of this imperceptible slippage of the present. So, as we leave the end of one year and begin another, I am thinking about time: the threatened loss of the present, the ways in which we necessarily inscribe ourselves into history, and writing not as a forgetting, but a remembering.